Augusta Wallihan was a hunter, wildlife photographer, adventurer, and conservationist.

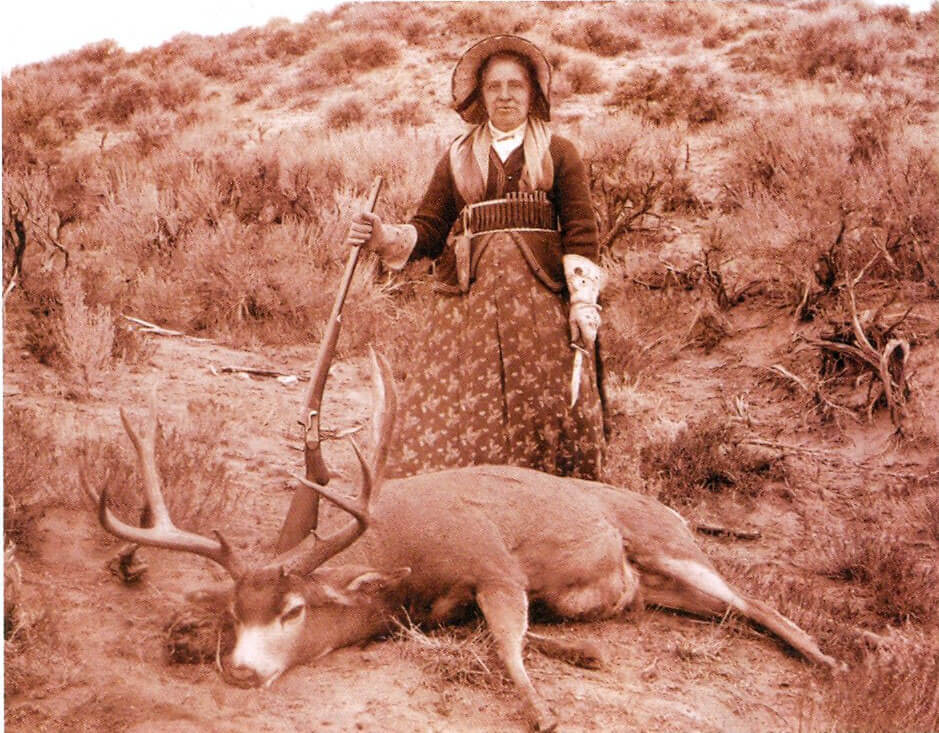

When I first saw the photograph of Augusta Wallihan entitled “Grocery Shopping,” I was intrigued and had to find out more. Who was this woman, dressed in the garb of the late 1800s and standing over a very nice mule-deer buck with a skinning knife and a Remington Hepburn rifle, exuding an air of confidence and competence?

As it turns out, Wallihan was even more interesting than I imagined. She and her husband, A.G. Wallihan, were among the first serious wildlife photographers in the United States, photographing deer, elk, bighorn sheep and myriad other big-game animals around their home in western Colorado. They gained international recognition for their photography and become influential conservationists as well.

Augusta Wallihan, nee Higgins, was born in Wisconsin in 1837 and made her way out West with her first husband. When that marriage failed, around 1880, she headed to Colorado to join her brother, Thomas Higgins, who had partnered with another Wisconsin expat, Allen Grant (“A.G.”) Wallihan, in a cattle venture. Wallihan family lore says Augusta and A.G. somehow ended up snowbound in an isolated cabin for several months, and to salvage their reputations they got married in April 1885 in Rawlins, Wyoming. At forty-eight, Augusta was twenty-two years older than A.G.

They homesteaded in the tiny town of Lay, Colorado, west of Craig, and A.G. became the town postmaster. While they owned a lot of land, they apparently weren’t cut out to be farmers. A.G. enjoyed hunting, though, and Augusta soon learned to shoot and also became a very successful hunter, keeping their larder well supplied with fresh meat.

It was a chance encounter with missionaries traveling through the region that led the Wallihans into photography. The missionaries had a camera with them, and Augusta traded them a pair of homemade buckskin gloves (maybe similar to the ones she is wearing in the “Grocery Shopping” photo) for their camera. Neither Augusta nor A.G. had any training in how to use it, but they quickly taught themselves the basics.

Photography in those days was in its infancy, and the cameras were massive, weighing ten pounds or more and mounted on tripod legs; most challenging of all, though, were the long, slow shutter speeds that required subjects to remain still. That made wildlife photography impractical, and most “wildlife” photos of the day were of mounted animals in dioramas. The Wallihans, skilled hunters living in a wildlife-rich paradise, had the opportunity and the ability to get close to living wildlife in order to photograph it-—but there was still nothing easy about it, and they often were lucky to get a single good photo of a deer, elk, or bighorn sheep in an entire day of attempts. After long days afield, they spent their evenings developing the negatives on glass plates.

Augusta was, by all accounts, a forceful personality, in contrast to her more laid-back husband. Nevertheless, they made an excellent team. While most of the photographs were credited to A.G., those who knew them said that their photography was a team effort. She was likely the driving force behind the increasing success of their careers, too; before long, their wildlife photographs were being reproduced in newspapers around the country, and they even had two books published. Both of the books, Hoofs, Claws and Antlers of the Rocky Mountains (1894) and Camera Shots at Big Game (1901) are credited to Allen G. Wallihan, but it’s certain the photos they contained were a team effort. As the Wallihans’ fame spread, they were invited to exhibit their photos at the Paris World Exposition of 1900. They exhibited again at the St. Louis World’s Fair four years later, and this time won a bronze medal for their work.

Augusta became widely known as an expert hunter and crack shot. In 1895, according to one source, she was invited to the Sportsman’s Expo at New York’s Madison Square Garden, where she hosted the Hunters’ Cabin. That had to be quite an honor. She was also something of an outdoor writer. I found an article she penned in the October 1895 edition of Recreation magazine entitled “How I Got My First Deer.” After telling the story of stalking her first buck and dropping it with a single shot, she casually mentions that she has since dropped thirty-one deer with her Remington, “only wounding three and losing none.”

Perhaps the most amazing thing about Augusta and A.G. was their concern for wildlife conservation at a time when it was the fashion to thoughtlessly eradicate as many animals as possible. In fact, it was one of the main motivations behind their photography—the Wallihans were sure that the wild game around them would soon go extinct, and their photos might be all that would be left. Their concerns were not unfounded, as commercial hunters operated indiscriminately throughout the West in those days, transporting wagonloads of meat to the cities where it was sold.

As the Wallihans wrote letters and articles calling for conservation measures and controls on hunting, they found themselves on the vanguard of a conservation movement that began to take hold around the turn of the century, led by visionaries such as Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell. Thanks to these efforts, hunters of today still have the opportunity to hunt and photograph the same big-game animals that Augusta Wallihan did more than a century ago.

Special thanks to the Museum of Northwest Colorado (www.museumnwco.org) in Craig, Colorado, for the images and information in this article, which appears in the Nov/Dec 2014 issue of Sports Afield.