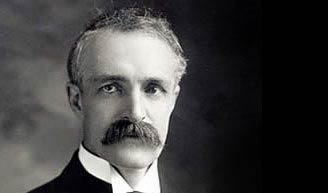

Editor, hunter, and conservationist, Grinnell made it his life’s work to save the American bison.

The life of George Bird Grinnell is an inspiring story of how one person can truly make a difference, even to the point of saving an entire species from extinction. Not only was he a driving force in wildlife conservation, Grinnell lived a life of high adventure, was an avid big-game hunter, and shared campfires with some of the most famous characters of the Old West.

Grinnell was the editor of one of the leading outdoor magazines of the late nineteenth century, a weekly publication called Forest and Stream, generally considered the forerunner of all other American outdoor magazines. He had a PhD from Yale and was also a naturalist, paleontologist, and a prolific writer. He studied and chronicled the fast-disappearing culture and lifestyle of Native Americans, helped found two major conservation organizations, and was largely responsible for the establishment of Glacier National Park. But he is best known for his heroic efforts to save the American bison from extinction, helping to establish a new American conservation ethic in the process.

Born in 1849 in Brooklyn, New York, Grinnell grew up on the country estate that once belonged to John James Audubon. The ornithologist/painter’s widow, Lucy, was one of his early influences, and his interest in the outdoors, wildlife, and hunting was sparked at an early age. He made his first trip West in 1870, shortly after graduating from Yale, with an archeological expedition led by one of his professors. It was a life-changing experience for the young Easterner, who collected fossils, saw elk and bison, and met Buffalo Bill Cody. He made three more trips west in the early 1870s, participating in a traditional bison hunt with Pawnee Indians, exploring the Black Hills with George Armstrong Custer (where they discovered gold), and studying the wildlife and natural history of the new Yellowstone National Park, created in 1872.

In 1876, back in New York, Grinnell landed a job editing a natural history column for the three-year-old outdoor magazine Forest and Stream. The magazine’s founder and editor, Charles Hallock, prided himself on pulling no punches when it came to excoriating hunters and anglers for unethical behavior. When Grinnell took over as editor and publisher in 1880, the magazine continued to be a strong proponent of the emerging conservation ethic, and one of Grinnell’s main targets was the situation in Yellowstone Park.

Grinnell used his popular magazine as a powerful platform to editorialize for protection of Yellowstone and particularly its bison, which were by then the only remaining wild bison in the country. Because Yellowstone was the nation’s first national park, no one seemed to know exactly what to do with it. The most pressing problem was a lack of law enforcement. Although a law had been passed, at Grinnell’s urging, prohibiting the killing of game within park boundaries, no provision was made for enforcement, and poachers had free rein to operate virtually unchecked. Grinnell spent years editorializing about the issue and lobbying Congress for action.

In 1885, Grinnell published a review of a new book by a young politician named Theodore Roosevelt called Hunting Trips of a Ranchman. His rather condescending review caused an annoyed Roosevelt to storm into Grinnell’s offices. The confrontation soon turned into an amicable discussion as the two men discovered their shared love of hunting and concern for conservation. Grinnell and Roosevelt soon began talking about creating an organization centered around sportsmen, and in 1887, at a dinner party at Roosevelt’s home, they and several other like-minded hunters formed the Boone and Crockett Club, which proved to be a driving force in the early conservation movement and greatly aided Grinnell’s work in achieving protections for Yellowstone and its bison.

A report published in Forest and Stream in 1894 of a thrilling raid on a poacher’s camp finally galvanized public and legislative support for enforcement and stiff penalties for poaching in Yellowstone. It was just in time–by the turn of the century, the park’s bison herd had dwindled to just twenty-three, and there’s no doubt that had it not been for Grinnell’s relentless efforts in the preceding two decades, the species would have become extinct in the wild.

Bison, however, were not the only focus of Grinnell’s conservation work. In an 1886 editorial, he wrote, “We propose the formation of an association for the protection of wild birds and their eggs, which shall be called the Audubon Society.” The very next year he launched the first issue of Audubon Magazine, which noted there were already 20,000 members in the newly formed association, which was dedicated to ending the commercial trade in songbird eggs and feathers.

And, even as he fought the Yellowstone fight, Grinnell was hiking and exploring in a region of northwestern Montana he called “the Crown of the Continent,” and he used his considerable resources–writing, editorializing, lobbying, and working with the powerful and politically connected members of Boone and Crockett–to champion legislation to turn the region into another national park. In 1910, his vision was realized when President Taft signed a bill creating Glacier National Park.

In his excellent 2010 book, How Sportsmen Saved the World, E. Donnall Thomas Jr. summed up Grinnell’s enormous contributions to the conservation community: “Grinnell convincingly demonstrated the power of a responsible outdoor press in the fight to preserve wildlife and habitat. His key role in the founding of the Audubon Society and the Boone and Crockett Club established important models for the numerous wildlife advocacy organizations that would arize in the twentieth century. Finally, he demonstrated that sportsmen could and would not just accept but champion appropriate restrictions on hunting when the common good called for it, as it did in the case of Yellowstone’s wildlife.”

Grinnell died in 1938 at age eighty-eight. The New York Times called him “the father of American conservation.”