The lever-action hunting rifle is as American as shootin’ irons can get.

Photo above: Among the traditional Winchesters in Barsness’s collection are (top) a .25-35 Model 1894 rifle made in 1898, with a 26-inch octagon barrel; a Model 64 .30-30, a fancier version of the 1894; and a Model 1886 in .33 Winchester, the first and only smokeless cartridge chambered in the 1886.

Lever-action hunting rifles are an American institution. While lever rifles have been manufactured and used elsewhere in the world, America’s hunting and military history encouraged the development of a fast-firing repeater with a magazine capable of holding plenty of ammo.

Before self-contained cartridges were developed in the mid-19th century, most American muzzleloaders were relatively small-caliber, so hunters and soldiers could carry more round balls. This changed when the western edge of European settlement crossed the Mississippi River, and hunters commonly encountered larger animals such as elk, bison and grizzly bears—the reason for the famous, larger-caliber rifles made by the Hawken brothers of St. Louis. But the small-caliber, light-ammo tradition still held east of the Mississippi, partly because “big game” mostly meant deer and black bears, and partly because that’s where most of North America’s early wars were fought.

Like most rifles, lever-actions were developed primarily for military use, and the technology was such a sudden, huge leap forward that some people feared for the future of human existence. European firearms designers concentrated on bolt-actions, because their military tradition involved massed troops firing at other massed troops. America’s military tradition was less rigid, partly because many soldiers were militia rather than professional soldiers, and often hunters used to acting independently. The first major lever-action success, and the rifle that became the mechanical basis for most later American lever-actions, was the Henry, with a tube magazine under its barrel holding 16 rimfire cartridges.

The Henry was a refinement of the Volcanic Rifle, a lever-action using a .41 caliber bullet that was also the “cartridge.” A deep hole in the back of the bullet was packed with black powder, then sealed by a percussion cap. In one of the ironic twists of firearms history, the Volcanic rifle evolved from a failed lever-action handgun, produced by the 1852 partnership of Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson, before they started making the first of their revolutionary cartridge revolvers. The Volcanic lost money, and Smith and Wesson sold the company to a group of “venture capitalists” put together by a clothing manufacturer named Oliver Winchester, and renamed the New Haven Repeating Arms Company.

New Haven’s head engineer, Benjamin Tyler Henry, then designed a more powerful .44 caliber rimfire round and an improved rifle. While .44 seems like a large caliber today it wasn’t then, and in fact the Henry’s major lever-action competition, the Spencer, used rimfire rounds loaded with .56-caliber, 350-grain bullets—but the Spencer’s magazine was inside the rifle’s buttstock, limiting capacity to seven rounds. While the Spencer cartridge was obviously more powerful, the .44 Henry was enough for hunting deer and fighting humans, and more Henry ammunition could be carried by a hunter or soldier.

The Henry saw some use by Union troops late in the War Between the States, when it famously became known to Confederate soldiers as “that damned Yankee rifle that can be loaded on Sunday and fired all week.” But technological change was rapid in the early days of cartridge rifles, and the Henry was only produced until 1866, when the renamed Winchester Repeating Arms Company introduced an improved rifle with a brass rather than iron receiver, named the Model 1866.

This first Winchester, nicknamed the “Yellow Boy,” was such an enormous success that it remained in production until 1899. Aside from being a very popular North American hunting rifle, over 50,000 were sold to various European armies, along with millions of rounds of .44 Henry ammunition.

Winchester continued to introduce new lever-actions throughout the 1800s on the basic mechanical plan of the 1866, with an ammunition loading gate on the right side of their steel receivers. Most were larger actions, in order to handle centerfire cartridges that kept growing longer, culminating in the John Browning-designed Model 1886. Big enough to handle the .50-110 black powder cartridge, the 1886 was also strong enough for smokeless powder.

In the 1890’s Winchester continued to introduce new lever-actions, all designed from the ground up to handle smokeless, from the small Model 1892 in .25-20 to the box-magazine 1895 in .405—which became famous as Theodore Roosevelt’s “lion medicine.” In between the Model 1894 appeared, the most popular lever-action ever made and still in production over 120 years later. (While the 94 has been chambered for cartridges from the .25-35 to .38-55, it became semi-synonymous with the .30-30, originally called the .30 Winchester Center Fire.)

By then other companies started making inroads into Winchester’s lever-action dominance. In 1870 John Marlin had started making rifles similar to the Winchesters, and in 1895 Arthur Savage introduced a sleek new design, a “hammerless” rifle with a 5-round rotary magazine inside the action. Neither Marlins nor Savages immediately rivaled the popularity of Winchester lever-action, but had features that, over the next several decades, became more important to hunters.

Entering the 20th century, Winchester lever-actions had two potential flaws, one the tube magazine used in all but the Model 1895, requiring blunt-nosed bullets. In tube magazines, the new “spitzer” (pointed) bullets being introduced in military ammunition could set off primers of other rounds during recoil—but spitzers shot far flatter, making accurate shooting possible at much longer ranges.

In the 21st century, of course, Hornady introduced spitzers with soft synthetic tips for tube magazines, but the blunt bullets necessary a century ago didn’t really matter much until telescopic sights started becoming more popular—which revealed another flaw in Winchester lever-actions: All ejected fired cases straight up, so scopes had to be side-mounted, not an ideal aiming arrangement. Both the Marlin and Savage lever-actions ejected to the side, leaving plenty of solid steel on top of their actions for scope mounts, and spitzer bullets could be used in the Savage rotary magazine.

Eventually, of course, bolt-actions started taking over the hunting market, especially after World War I when so many returning American soldiers had grown used to 1903 Springfields and 1917 Enfields. Winchester’s only “new” centerfire lever-actions during the first few decades of the 20th century were minor variations on earlier models, including 1935’s Model 71, a slightly modified Model 1886 chambered for only one round, the .348 WCF. The 71 had the bad luck to appear at the lowest ebb of the Great Depression, and only six years before American entered World War II, and factories were converted to making military firearms.

After the war scopes took over, and though some lever-actions could be easily scoped, more hunters bought them due to tradition than practicality. Some eastern deer hunters still preferred light, iron-sighted levers like the Model 94 Winchester and Marlin 336, and some bear guides liked big-bore levers, but eventually far more hunters viewed lever-actions as semi-antiques, partly because they supposedly weren’t as accurate as bolt-actions.

This isn’t necessarily so. Over the decades I’ve owned a pair of levers that shot as well as any of my bolt-actions except my benchrest rifle, a Savage 99-EG in .300 Savage and a Browning BLR .30-06. However, neither had a trigger pull as good as most bolt-actions, though after working the 99’s over it wasn’t bad. Still, even many hunters who use lever-actions don’t usually choose them for trophy hunting—and I confess to being one. Mostly my levers go on “fun” hunts, for varmints or meat.

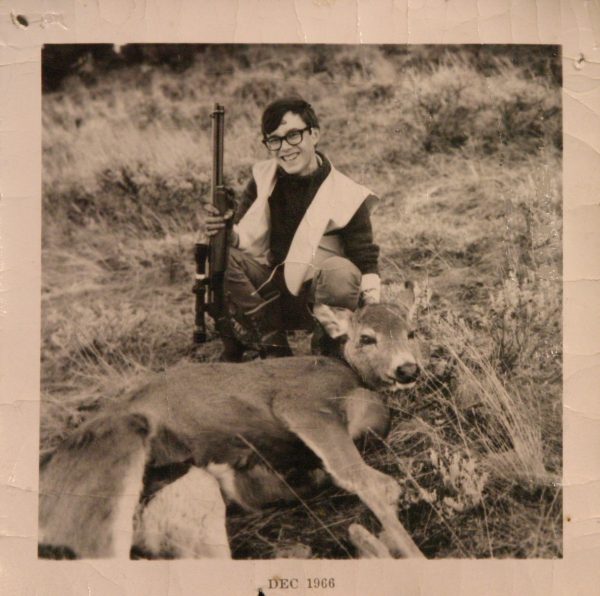

In fact my very first big-game animal, a mule deer doe, was taken with a Marlin 336 .30-30—my father’s rifle, purchased partly because his eyesight was so bad he absolutely needed a scope. My shot was so close the 4x only showed a slightly fuzzy view of the deer’s shoulder area, and I probably could have killed the doe without any sights at all. Aside from that first deer, all my hunting with traditional, outside-hammer lever-actions has been with iron sights, while my Savage 99’s have mostly used scopes.

Some hunters do use levers for trophy hunting. When a friend and I decided to do an iron-sight safari in Botswana in 2003 my primary rifle was a Ruger No. 1 in .375 H&H, but he took a Winchester 1886 in .50-110, loaded with black powder and hard-cast bullets. It was a package deal for Cape buffalo and four species of plains game from warthog to kudu, and we both took the same animals with no problems—though he put several more rounds into his buffalo, after having pretty much anchored it with the first shot. He also took an impala at over 200 yards, adjusting the “ladder” on the buckhorn rear sight for the range.

There’s no reason not to use an accurate lever-action with spitzer bullets and a modern “turret” scope for longer-range hunting. You might get some weird looks from fellow hunters, especially those who refuse to hunt with anything but a synthetic- stocked, stainless-steel bolt rifle and who think anything less is almost as much of a handicap as a longbow. That obviously isn’t true, as thousands of hunters taking big-game animals with “primitive” lever-actions have proven over the past century and a half.

Barsness’s first big-game animal, a mule deer doe, was taken with a scoped Marlin .30-30.