Proof that giants still walk among us.

Photo above: Crossing the Tana River in Kenya with big ivory in the 1960s, a scene that will never be seen again. (Photo by John Dugmore)

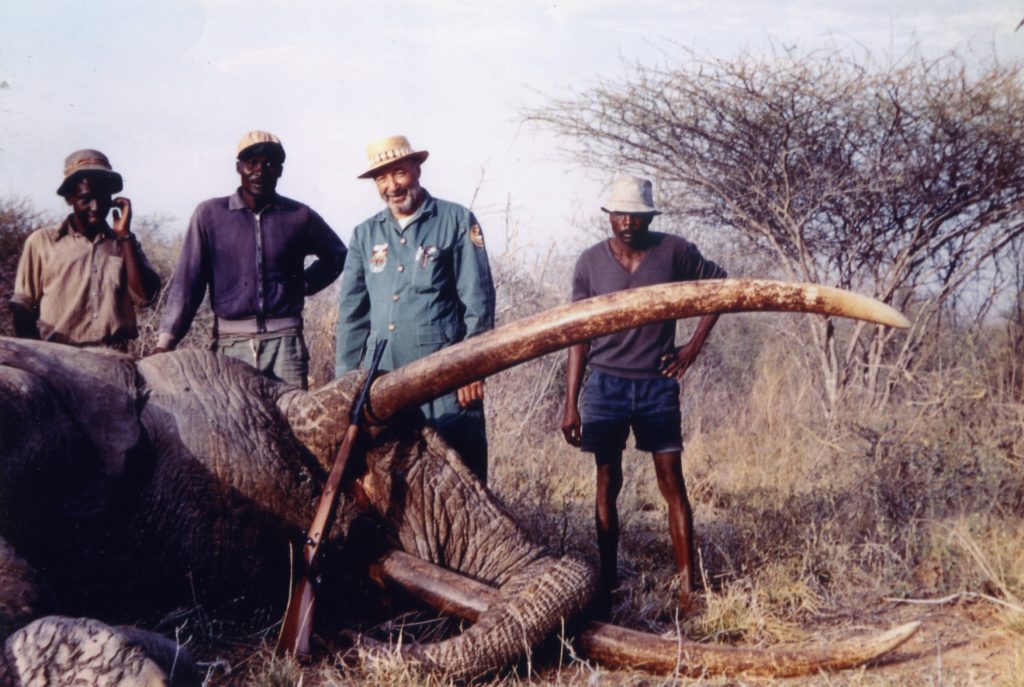

On May 8, 2019, my old friend Michel Mantheakis from Tanzania and Namibian PH Koos Pienaar, hunting in Namibia’s eastern Caprivi, guided their client to an amazing elephant with the major tusk weighing 100 pounds. To me this is big news, and it is not sad news. This was not a known, named, or iconic park elephant; it was an exceptionally large elephant bull taken during a legal season in a hunting area that has a known overpopulation of elephants. Its harvest provides proof that giants still walk among us.

Tanzanian PH Michel Mantheakis with an exceptional tusker taken together with PH Koos Pienaar in Caprivi, May 2019. The major tusk is right at 100 pounds, a big elephant anywhere and a most unusual elephant in the southwest corner of Africa.

For more than a century, the Holy Grail of elephant hunting has been to find an elephant with one or both tusks exceeding the 100-pound mark. With older elephants, one tusk is often worn shorter or broken, suggesting the elephant was left- or right-tusked. The Rowland Ward records always recorded the weight of both tusks, but ranked their tables on the heaviest tusk. In more recent times they have changed this to ranking on the combined weight of both tusks. SCI listings also take the combined weight of both tusks. Either way, an elephant carrying 100 pounds of ivory on either side is an amazing creature. I have never seen such an elephant, and I probably never will, since I consider my elephant hunting in the past.

I have also never taken, and probably have never seen, a Boone and Crockett whitetail buck, but I know such exceptional animals exist. B&C’s position is that their records of North American big game exist not for glorifying the hunter, but because the presence of exceptionally large animals is an indicator of a herd’s overall health.

This bull is showing a lot of tusk length and he immediately catches your eye…but he’s a young bull and the tusks are very thin. Despite the length, there’s no weight here, less than 30 pounds in the visible tusk.

With elephants this is tricky, because, sadly, elephants have been greatly reduced in many areas once known to produce heavy ivory. While a “hundred-pounder” is the magical mark, historically they do get bigger. The heaviest tusks known were taken on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro in 1886, 226 and 214 pounds, the only tusks known to exceed 200 pounds. Rowland Ward lists two dozen elephants with one tusk exceeding 150 pounds; and 132 elephants with one tusk exceeding 120 pounds. Forty-six of these super-elephants came from Kenya, nineteen from Tanzania, eleven from C.A.R., and ten from Sudan. To some extent this reflects popularity of hunting areas, but of these four countries, only Tanzania still has a significant elephant population, and only Tanzania remains open to elephant hunting.

Next in line, with nine 120-pounders, is South Africa. The Kruger Park ecosystem is known to produce extra-large ivory (sometimes!), seemingly a mysterious and unknown combination of genetics, food, and minerals. When exceptional elephants are identified in Kruger, extreme measures are taken to protect them as national treasures, which I find appropriate. Also, in the areas around Kruger where elephants are hunted there is generally an upper limit on legal tusk size, to conserve the rare giants and their genes, which I also find appropriate.

As for the rest of the continent, there is no pattern of extra-large tuskers. Uganda is sixth with six 120-pounders, then D.R.C. (Zaire) with three, and then it’s ones and twos: Cameroon, Ethiopia, Ivory Coast, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Togo, Zimbabwe . . . and more than a dozen 120-pounders with origin unknown. Of these last countries mentioned, more than half have few elephants remaining.

Very significant to today’s elephant hunting: No elephants with a 120-pound tusk are known to have been taken in Angola, Botswana, Namibia, or Zambia. Botswana suspended safari hunting on government land five years ago, with the announcement just made that it will reopen to hunting. Botswana holds by far the continent’s largest elephant population, perhaps 250,000. They are overpopulated, with crop and habitat damage escalating rapidly. Under such conditions, elephant hunting is an almost essential management tool, and certainly this is great news. The elephant hunting will be spectacular, but we mustn’t think hundred-pounders will lurk behind every baobab tree. The track record just isn’t there.

Namibia’s Caprivi is a narrow strip of land with Botswana to the south, Angola to the northwest, and Zambia to the north. An elephant can walk across it overnight, and they do. The hundred-pounder just taken is not the only one from Namibia, but it’s the first I’ve heard of in a while. In 2010 PH Willy MacDonald guided a client to a 104×99 pounder in Botswana. This stands as the largest tusker since Botswana reopened elephant hunting in 1996. Botswana has an annual CITES quota of three hundred bulls, so this is one hundred-pounder in about five thousand bulls taken.

MacDonald was honest about the encounter. His client wanted to know how big it was; Willy told him he had no idea because he’d never seen such an elephant! It’s hard to judge any animal exponentially beyond your experience. I’m pretty good at whitetails from the 140s to 160s, but I doubt I could judge a 180-inch whitetail because I’ve never seen one, and probably never will. I know Koos Pienaar by reputation, and I’ve hunted elephants with Michel Mantheakis. He’s a careful and diligent hunter, and exceptionally good at judging quality. But, when they confronted this elephant, I don’t know if they recognized they were looking at the Holy Grail, or if they just knew, despite one broken tusk, it was too big to pass.

A mature elephant in the 40-pound class.

A mature elephant in the 40-pound class.

The formula is simple: First, you estimate the length of ivory showing beyond the lip. Mantheakis is especially good at this because tusk length is one of Tanzania’s legal minimum standards (either length or weight). Then you estimate circumference at the lip. Angola/Caprivi/Botswana elephants are much bigger than Tanzanian elephants, typically with thicker ivory. Pienaar was on his home turf and would have known. The major tusk had 53 inches of ivory beyond the lip, with a circumference of 21.5 inches. Take exposed length in feet (53 divided by 12 equals 4.4 feet) times circumference in inches: 4.4 x 21.5 = 95 pounds. This odd math is usually very close; the unknown variable is the size of the nerve within the tusk. This bull had a small enough nerve to yield a bonus; it can just as easily go the other way. When Michel sent me a photo, I underestimated the circumference. My guess was way off, but I’m not Michel Mantheakis or Koos Pienaar, and I’ve never seen such an elephant.

Truth is, no modern hunters have experience judging this kind of elephant; they are just too uncommon. Historically, few ever did! But in the days when a really big tusker was a possible prize, there were professional hunters who specialized in seeking, finding, and hunting exceptional elephants. Bror Blixen and Denys Finch-Hatton are said to be among them. For sure Eric Rundgren, who apprenticed under Blixen, was one of the best. I don’t think Harry Selby would have put himself in that company as a big elephant specialist, but perhaps he belongs. Selby guided Robert Ruark to an astonishing three hundred-pounders, and took quite a few with other clients. Selby’s next-door-neighbor in Maun, John Dugmore, apprenticed under Eric Rundgren, so there’s probably a pattern here. In Kenya’s latter days, Dugmore did a lot of horse-and-camel safaris in Kenya’s Northern Frontier District and guided clients to an exceptional number of big East African tuskers.

A big Kenya tusker with long East African ivory, right at 100 pounds. The cool thing about this photo is the rifle, an early Winchester Model 70 African in .458, so this photo is from about 1960, a time when big tuskers could be effectively sought…in the right places at the right time. (Photo by John Dugmore)

Unfortunately, the hunters who saw big tuskers in numbers are almost gone, and so are the big elephants they pursued. In the old days they theorized that an elephant bull grew a pound of ivory per year, so a hundred-pounder should be a century old. This is not true. It is true that elephants grow both body mass and ivory throughout their lives, although growth slows with age. Longevity is determined primarily by tooth wear. The elephant has six sets of molars that grow progressively into place. When the final set wears out, the animal will starve, usually in its sixties. In soft, loamy soil like the slopes of Kilimanjaro that produced the world record, tooth wear is retarded, and an elephant can theoretically live longer, but an elephant living a hundred years is somewhat less likely than you or I achieving that mark.

Elephants put on a lot of ivory in their middle years, easily two or three pounds per year. No elephants have been taken in Botswana for five full seasons, and it’s been ten years since I hunted there. This should mean a perfect young 40-pounder I passed ten years ago might carry 60- or 70-pound tusks today.

I hope so! I have no desire to hunt elephants again, but I want elephants to be properly managed. In the overpopulated southern Africa herds, carefully regulated hunting is an almost essential part of that management. After her five-year suspension, Botswana has come to that conclusion, in my view a wise decision for her people and her wildlife. Botswana not only has Africa’s largest elephant population, she also hosts Africa’s largest-bodied elephants, 7-ton giants standing 12 feet and more at the shoulder. They grow tusks that are typically short and thick, but only rarely attain extreme weight. But there are hundred-pounders out there, and when Botswana reopens, a few of them will be seen.

Emotions aside, where most elephant hunting is conducted today the elephants are overpopulated and must be managed, and recovery of all meat, which goes to local villages, is an important byproduct of the hunt.