Everything you need to know about hunting the various types of wildebeest.

There are two species of wildebeest: the black wildebeest, also called white-tailed gnu; and the blue or brindled wildebeest. The black wildebeest is native to South Africa’s central plains, and prefers much more open country than the blue, so it lay square in the path of Voortrekkers moving up from the Cape. Almost exterminated in those early days, the black wildebeest was almost miraculously saved from extinction by forward-thinking Boer farmers. It is now plentiful on South African game ranches and has been widely introduced into Namibia. The black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnu) has no identified subspecies.

The blue wildebeest (C. taurinus) is common in East and Southern Africa. Several subspecies are identified but, as hunters, we boil them down to four in our record-keeping systems. North to south: white-bearded, Nyasa, Cookson, and blue.

Although they have sharp eyes, wildebeest are generally not among the warier antelopes. The most difficult part is usually picking out a bull. They are nervous, constantly shifting herd animals, and both males and females have horns that, at first glance, appear similar. I think of them of as classic “common game,” offering excellent meat (enough to feed a camp or a village), interesting horns, and gorgeous skins.

By 1988 I had taken black wildebeest and all the races of blue. So, I thought I knew a thing or two about the gnu. Cookson wildebeest has the most limited range and lowest numbers, essentially confined to Zambia’s Luangwa Valley. I was there recently, accompanying son-in-law Brad Jannenga on a hunt in North Luangwa. On about the third day, in need of meat, we ran into a small herd of wildebeest, shadowed in dense mopane. Brad shot a nice old bull, and when we got him out into sunlight, I learned some things I didn’t know.

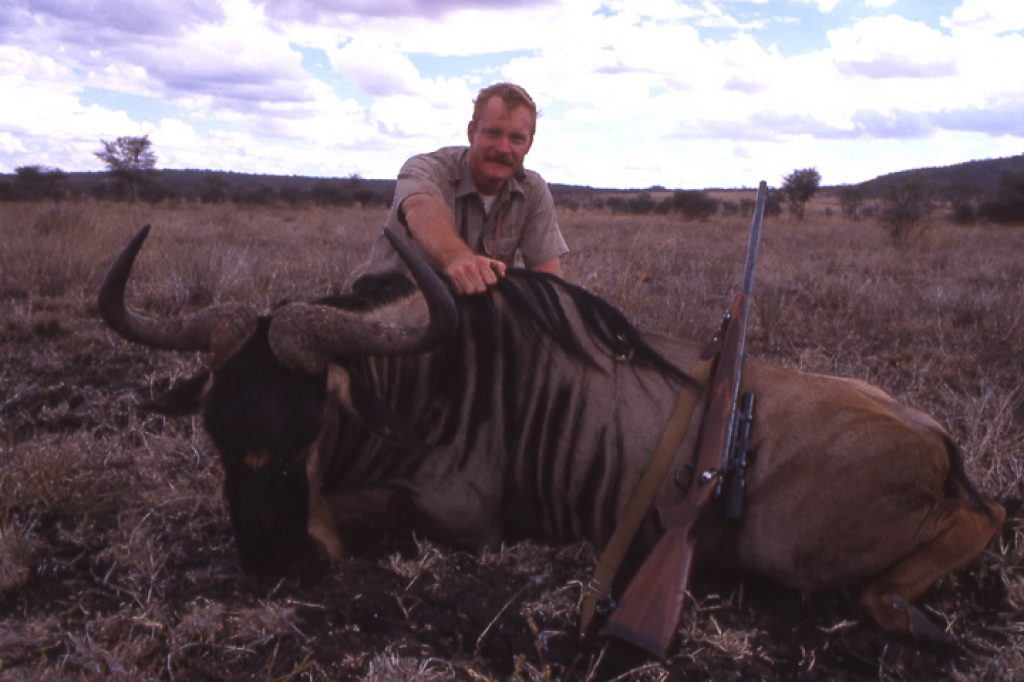

I took a nice wildebeest in the Luangwa clear back in 1983 and, ever since, have given myself credit for having a Cookson wildebeest. Technically, yes, but mine sure didn’t look like this animal! Mine had some proper color but was not as brilliant. Forty years ago, I didn’t know what to look for. Brad’s bull had a light, very gray background color, with black vertical striping from mid-section forward to neck. In good sunlight, it looked like a cross between an antelope and a zebra. So, what I didn’t know: The light color with dark striping defines Cookson wildebeest.

We were in the northernmost concession of the Luangwa Valley. The true, proper Cookson wildebeest is really a North Luangwa animal and occupies a small range. As you move south, it merges into the common blue wildebeest.

The white-bearded wildebeest, with light body color, is distinctive with cream-colored neck ruff. Found only in northern Tanzania and southern Kenya, it is possibly the most numerous because of the huge Serengeti migration, but is actually difficult to obtain because Tanzania is the only opportunity, and it does not occur in all Masailand concessions. At the tail end of a 1988 hunt, we caught a herd on the Simanjaro Plain on the edge of Tarangire National Park, and that’s my only white-bearded wildebeest.

Tanzania is also the primary opportunity for Nyasa wildebeest. I’ve never seen them in big herds, but this wildebeest is commonly encountered in Selous Reserve, and ranges from southern Tanzania well down into Mozambique, also native to Malawi (former Nyasaland), but is considered extinct there. The Nyasa wildebeest is the smallest of the blue wildebeest in both body and horn. I’ve shot several in Selous, and they seem to be uniformly milk chocolate in body color. The most distinctive feature is a white nose chevron, not dissimilar from that of a spiral-horn antelope.

The blue wildebeest is the most widespread, relatively common in southern Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Botswana, and throughout much of South Africa and Namibia. Color varies from dark gray (almost blue) to brown with darker striping (the “brindled” effect of its gnu name). Cookson wildebeest is said to be larger in body, but the common blue probably has the largest horns.

With wildebeest you look for mass and curve on the horn but, unlike other antelopes, we commonly speak of blue wildebeest in terms of extreme spread: A “thirty-inch” wildebeest is the Holy Grail and a rare prize. I shot such a bull in Botswana’s Okavango clear back in 1985. One of the best (or luckiest) shots I ever made; I was shooting an open-sighted .318 Westley Richards, distance about 250 yards. The big bull collapsed on the spot, but I doubt I could repeat such a shot–certainly not today with iron sights!

The black wildebeest is quite different in color, body shape, and horn configuration, clearly deserving of its separate species identification. It is uniformly dark brown to almost black, with a weird forehead brush like a Mohawk hairdo. It is slightly smaller, and the shoulders aren’t as massive as the blue wildebeest. The horns are totally different, and differentiating males from females is more difficult. Bulls have huge bosses nearly together in the center, the horns coming straight down and then curving up into long tips. My first was in 1979, a top-ranking bull back then, when South Africa was just opening up and the black wildebeest was in short supply. Now they are common and that bull would be very average. I’ve only shot one more.

Wildebeest are sometimes described as “the poor man’s buffalo” and “clown of the African bush.” I don’t like such appellations, but neither are completely inaccurate. As to the former, wildebeest are not remotely dangerous! They are, however, buffalo-like in shape and it takes experience to sort bulls from cows. As with buffalo, we look at thickness of bosses or bases and shape. With the brindled gnus, like buffalo, we also look at spread.

As to the latter, the wildebeest puts on the weirdest antics. For no apparent reason, bulls will suddenly put their heads down and canter around in circles. This erratic behavior caused the early Dutch settlers in South Africa to name them “wild beast.”

There’s no peril to hunting wildebeest, but they are buffalo-strong, in my view one of the hardiest antelopes, and also larger than they appear at distance. A big blue wildebeest bull can weigh a quarter ton and, pound for pound, is tougher than its size.

Like all the antelopes with exaggeratedly tall shoulders, the greatest risk and most common error is to hit them too high. Concentrate on a third up from the brisket line and there should be no problem, but hit a wildebeest poorly and you can expect a long tracking job! I’ve never lost a wildebeest, but that’s only through great tracking (and some luck). I’ve had some very long days following wildebeest that were hit less than perfectly.

One, on Barry Burchell’s place in southern Namibia, was shot with a .264 and recovered miraculously six hours later. The first shot was frontal, right height, but I wavered off center just a bit. Not a matter of not enough gun, but not a good enough shot! With proper shot placement, I’ve seen big-bodied blue wildebeest taken cleanly with .260 Remington, 7mm-08, and 7×57. Of course, the .270 Winchester, faster 7mms, and .30-calibers are just fine.

That said, I have huge respect for wildebeest, and I’ve wasted a lot of precious hunting time tracking them. So, if I happen to have a .375 on hand, I’m happy to use it when there’s a wildebeest in the offing.

Years ago, in Namibia, Dirk de Bod and I spotted a herd in late afternoon. There was a nice bull in there; we stalked them endlessly, trying to get him in the clear. Sunset came and went, and the light was going fast when I finally got a shot. That’s a risky time to shoot anything, but especially such a notoriously tough animal. The herd bomb-shelled at the shot, and the direction of the bull was unclear and no blood was obvious in the growing dusk. Fortunately, I was carrying a .338 stoked with 250-grain bullets. We were just about to call for the truck and get flashlights when I stumbled over the bull, stone dead. It had only gone fifty yards.