The Selous, Africa’s largest hunting reserve, is being destroyed.

Photo above: The dam construction site at Steigler’s Gorge. Photo: Archive Baldus

The Selous Game Reserve was once Africa’s oldest and largest nature reserve. It was established by Germany in 1896; at more than 31,000 square miles, it was twice the size of Vermont. It was recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1982, one of the most important natural monuments on earth. It was one of the leading hunting grounds in Africa, and hunting proceeds kept the reserve going for many decades.

Tanzania’s government has traditionally held the protection of the country’s rich wildlife in high regard, although in practice conservation performance was often lacking. In the Selous, mismanagement, lack of funds, and bad governance has twice led to serious episodes of commercial poaching, which reduced the rhino and elephant populations. This happened in the first half of the 1980s, and again between 2006 and 2013.

Germany, together with Tanzanian partners, rehabilitated the Selous between 1987 and 2003. Elephant numbers rose during this period from 30,000 to over 70,000. One of the most important achievements was the introduction of a system of self-financing. The Selous was allowed to retain half of its income and use it for running costs and investment. In the mid-1990s, this was $3 million dollars, 90 percent of which came from hunting. Thus, international hunters, most of them from the United States, safeguarded one of Africa’s last remaining wildlands and facilitated the conservation of its wildlife, including elephants, lions, leopards, and plains game.

After the project ended, however, the Tanzanian government broke all agreements for self-financing of the reserve. Poachers once again targeted the elephant population, with quite a few senior politicians and officials participating. The elephant population fell from more than 70,000 in 2005 to 13,000 in 2013. Value of the looted ivory: over 100 million Euros.

Another disaster befell the reserve in 2012, when a uranium mine in the southwest of the reserve was permitted. This is against the rules for a World Heritage Site. Tanzania promised, however, that this would be the last major violation of the ecological integrity of the Selous. Nolens volens, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee swallowed the toad.

President John Magufuli has been in office since 2015. A former minister for roads and infrastructure, he loves large projects and has no regard for nature, neither for its intrinsic values nor for its ecological and economic significance. In addition, he is increasingly turning into an autocratic ruler. In flawed elections last October, his party got a North Korea-like 98 percent of all seats, and he was re-elected.

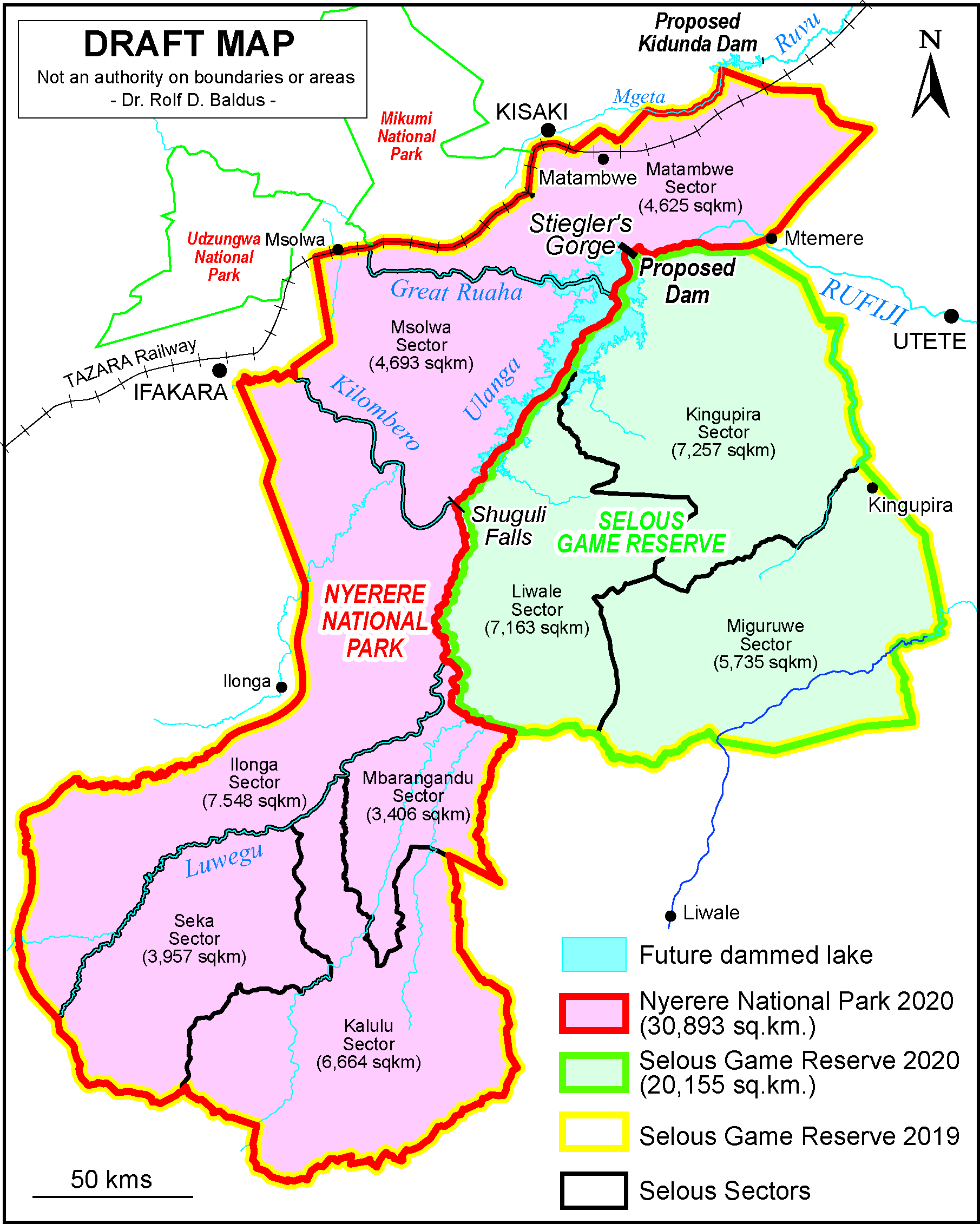

As his latest mega-project, Magufuli is having Egyptian and Chinese construction companies build a huge dam with a 2.2 megawatt power plant at Stiegler´s Gorge on the Rufiji River in the heart of the Selous for an estimated 10 billion US dollars. He wants to use the electricity to industrialize Tanzania. Whether that will work is questionable. A serious analysis of the environmental impact, economic efficiency, or financial viability is lacking. What is for sure is large-scale damage to the game reserve. The reservoir alone will flood 500 square miles, including some of the most beautiful and valuable areas of the reserve and one of the last habitats of the black rhino in Tanzania. Another dam is to be built at the northeastern corner of the reserve on the Ruvu River.

The president does not think highly of sustainable hunting. In his eyes, it has no economic significance for the country. He spent one night in the Selous in the VIP suite of a lodge. This suite is equipped with air conditioning, satellite TV, and a Jacuzzi; however, it is mostly unoccupied due to the price. When he heard that the suite cost $2,000 per night, he quickly calculated this for 365 days and all tourist accommodation in the Selous. Compared to that sum, he said, hunting is unprofitable.

Hunting blocks throughout the country have been released for agriculture under his rule, and others have been declared national parks. The Selous is now divided. The western and southern part, with about 19,000 square miles, has become the Nyerere National Park. Only the smaller, eastern part (about 12,000 square miles) will be hunted in the future. The division was done without the legally required planning procedures.

Large parts of the new national park could be hunted sustainably, but are unsuitable for phototourism (this region is not attractive for tourists, has a long rainy season, is tsetse- and malaria-infested, and is remote and therefore logistically expensive). The new park has become a financial drain for the Tanzania National Parks Authority (TANAPA), while at the same time the hunting administration is losing millions of dollars in revenue. Only three national parks in the country generate any surpluses at all. All others are lose money and are cross-subsidized. The most money is earned at Kilimanjaro, Africa’s highest mountain. Without the high-priced mountaineering traffic, TANAPA would have had to file for bankruptcy long ago.

To make matters worse, the government has decided, in view of empty coffers, that the three previously autonomous nature conservation authorities: TANAPA; the Ngorongoro Crater Administration; and the Tanzania Wildlife Authority, which covers the hunting blocks and all other conservation areas, must submit all of their revenues to the state. Then they will receive state subsidies. Such a system existed decades ago. It resulted in a pronounced underfunding of the nature reserves and massive poaching.

In any case, hunting income in Tanzania has fallen by more than half in recent years. There are several reasons for this: Mismanagement of the hunting administration, excessive government taxes and fees, several failed auctions to allocate unused hunting blocks, a trophy import ban by the USA, and now, the coronavirus.

In the meantime, dams and mining are not the end of the story. An extensive program for the construction of a road network is on the way. It is becoming obvious that one of the last largely untouched wilderness areas in Africa is gradually being dismembered. Hunting, with its small environmental footprint, has so far preserved nature. The national park, however, will result in infrastructure, hotel buildings, and roads. Experience shows that such roads are not only used by tourists, but also by charcoal trucks, poachers, and through traffic.

The World Heritage Committee declared the Selous a “World Heritage in Danger” some time ago. At the next General Assembly of the Convention, the 194 member states have to decide whether the status will be withdrawn from the Selous altogether. It seems that the “Outstanding Universal Value” of the Selous Ecosystem has been surrendered by the government of Tanzania. Hope dies last, but today there is little hope left. Hunters are losing one of the last wilderness areas in Africa.—Rolf D. Baldus