If you’ve seen “The Revenant,” you might think you know. But there are many versions of the story.

Probably the most famous “true story” from the mountain man period of the American West is the saga of fur trapper Hugh Glass. The generally accepted version goes something like this: Attacked by a grizzly, severely mauled, Glass is considered beyond saving and is left behind to die. Two fellow trappers, one of whom is the young Jim Bridger, are paid to stay with him until the end and provide a proper burial. But Glass hangs on. The men are increasingly worried about nearby hostile Indians, who might discover them at any time. So they abandon the dying man, taking his rifle, knife, and other vital gear. Glass is left on his own, deep in the wilderness. But somehow he manages to survive, drinking stream water, eating berries and whatever else he can find for sustenance. His wounds are terrible–he can’t stand or walk–but he slowly gains enough strength to begin crawling over the prairie, aiming for a fort hundreds of miles away. He is driven by a fierce will to live and a burning desire for vengeance on the scoundrels who robbed him and left him for dead.

It is, of course, the stuff of legends, and a great story, which is why the Glass story has been told and retold, first as ostensibly true accounts, then as blatant fiction in novels and movies, most recently The Revenant. “Everyone knows” about Hugh Glass, but as is often the case with what everyone knows, it turns out that much is doubtful or plainly false. In fact, there isn’t one Hugh Glass story, but several conflicting versions. Some historians even believe the whole chronicle is largely made up, a tall tale first spun by Glass and then embellished by others. Let’s take a closer look at some of the details.

Little is known about Glass’s origins, but it is believed he was born circa 1780, near Philadelphia. At the time of the bear attack he was probably in his mid-forties, which was elderly for a mountain man and explains the frequent reference to him as “Old Hugh,” or “Old Glass.” He spoke of being a sailor in his early years and claimed to have been captured, along with a comrade, by the notorious pirate Jean Lafitte. They were given the option of joining the plunderers or dying; naturally they chose life. After a miserable year with the pirate colony, word came that they were going to be tried as unworthy and executed the next day; so they jumped ship in the middle of the night and swam to the Gulf-coast shore near present-day Galveston. Here they made their way with difficulty, living off the land while avoiding the dangerous Karankawa Indians, who were said to be cannibals.

When they reached the Great Plains they were captured by the Pawnees and slated to be tortured and burned alive. Glass’s companion went first. He was stripped, tied to a stake, and impaled with dozens of pitch-pine slivers, which were then set afire. Glass made himself watch stoically, showing no emotion or fear. When his turn came he bowed slightly and offered the chief a packet of vermilion he’d been (somehow) carrying. The chief found this display of courage and grace impressive. He decided to spare Glass’s life and adopt him into the tribe. By one account Glass lived with the Pawnees for several years before making an escape; another says it was several months. From the Indians he learned survival skills such as how to forage for wild edible plants. Later he entered the western fur trade, eventually enlisting in Major Andrew Henry’s trapping expedition up the Missouri. By late summer or early fall of 1823 he and his group were traveling by foot along the Grand River in present-day South Dakota, heading for the Yellowstone country. It was here he met the grizzly.

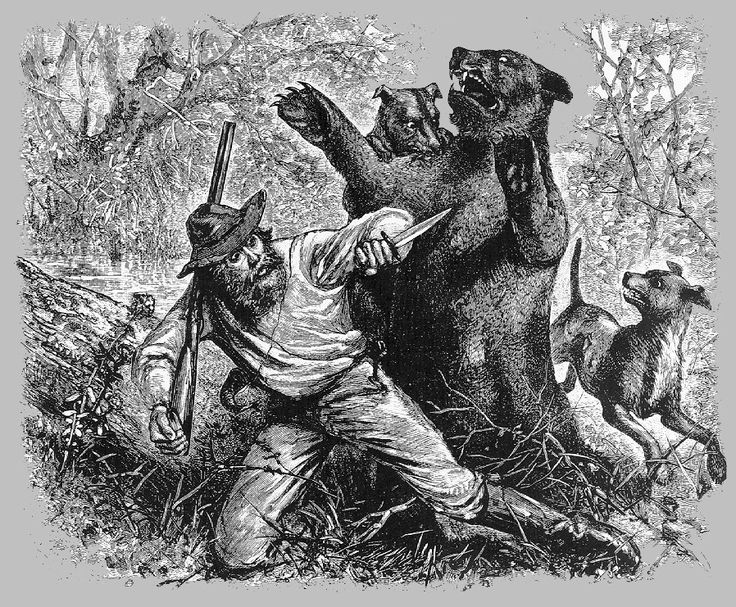

According to one account, Glass and another man were sent ahead of the group to hunt for game, when he suddenly encountered a “white bear” (as grizzlies were often called) only three yards away. Before he “could set his triggers or turn to retreat, he was seized by the throat and raised from the ground,” then mauled viciously. But other accounts put Glass at fault. Disobeying orders to stay in close file because of nearby hostile Arikaras, Glass “went off of the line of march….and met with a large grissly Bear which he shot at and wounded,” trapper James Clyman recorded in his journal. Then the bear–a sow with near-adult cubs–attacked. In words attributed to another trapper, Hiram Allen, who was at the scene: “…the monster had seized him, torn the flesh from the lower part of the body, & from the lower limbs–He also had his neck shockingly torn, even to the degree that an aperture appeared to have been made into the windpipe, & his breath to exude at the side of the neck.” Allen noted that Glass’s arms and hands were unhurt, and he suffered no broken bones. (This despite the several versions of the story that say Glass later set his broken leg himself.)

After the bears were killed, the group did what they could for Glass’s wounds, but considered the man a goner. By one account, they then left him to his inevitable death, taking his gun and equipment with them. But in other versions the trappers built a litter and placed the torn man upon it, laboriously carrying him for several days. Glass “retained all his faculties but those of speech & locomotion.” He was “too feeble to walk or help himself at all, his comrads every moment waited his death.” But the tough old mountaineer wouldn’t die. Finally the difficult decision was made to leave him behind. Two men agreed to stay until the end and provide a proper burial–for a fee. (Eighty dollars in one account, $300 in another, or $400–a near fortune for those times.) One man was John Fitzgerald, and the other was a mere boy of 18 or 19. “Bridges,” was the name first reported. Much later–more than 70 years after the event–a prominent historian would use an elderly man’s second-hand recollection to conclude that the boy at the scene was in fact the now-famous mountain man Jim Bridger. This became accepted as part of the story, though some, including Bridger’s main biographer, strongly deny it. (When interviewed in his later years, Bridger recalled the Glass incident but made no mention of playing any part in the drama.)

In any case, after some days (two, three, or five) the care- givers began to worry. Glass kept hanging on. An escalating fear of nearby Arikaras and the increasing distance from the main band were wracking the men’s nerves. Fitzgerald convinced the youth it was time to depart. Just take Old Hugh’s gun and gear and leave him to his inevitable death, which could come any time now. In two accounts, Glass is asleep when the men slip away, and wakes to the horror of being disabled and alone. In another version, Glass hears them planning to abandon him, but cannot speak. He can only plead with his eyes and reaching hands.

Some say the two men took everything–gun, knife, pouch, kettle–leaving Glass on a pallet with just his clothes and a blanket. In a different telling, they left a kettle containing his wallet and an old razor–a precious cutting tool he would later use to survive.

Glass’s reaction varies with the source: 1) “He didn’t despair.” 2) “Oppressed with grief and his hard fate, he soon became delirious.” But then, “visions of benevolent beings appeared…. exhorting him not to despond.” Whichever, he drank water from a nearby stream and ate wild berries to sustain himself. He rested over many days and planned a course of action.

The Crawl

The four original “true accounts” of Glass’s ordeal vary considerably in significant details. In the earliest publication (by James Hall, 1825): “Acquiring, by slow degrees, a little strength, he now set off for Fort Kiowa, a trading establishment on the Missouri River, about three hundred and fifty miles distant.” (Actually, 200 miles.) “It required no ordinary portion of fortitude to crawl…through a hostile country without fire-arms, with scarcely strength to drag one limb after another, and with almost no other subsistence than wild berries.” In Hall’s version as in one other, Glass drags himself the whole way to the fort.

In a perhaps more reliable rendition by trapper George Yount, who claimed to have gotten the story from Old Hugh himself, Glass did build up his strength by drinking creek water, resting and eating berries. But “one morning…he found by his side a huge Rattlesnake–With a small stone he slew the reptile, jambed off its head & cast it from him–Having laid the dead serpent by his side he jambed off small parts from time to time & bruised it thoroughly & moistened it with water….& made of it a grateful food on which he fed from day to day…After a long period his strength began to revive.” He “crawled a few rods” and then rested, building his stamina. Eventually he “found himself upon his feet & began to walk–Soon he could travel nearly a mile a day.” He fed on buffalo carcasses along the way; and once drove a pack of wolves from a fresh kill, gorging on the raw meat. He ate berries and “nourishing roots” dug from the earth, as he had learned from the Pawnee.

Most accounts agree that he drove himself forward with a near-feverish lust for revenge on the two men who had stolen his rifle and gear before leaving him to die.

In two versions, when close to collapsing he came upon a band of friendly Sioux, who gave him much-needed food, tended his wounds, and helped get him to Fort Kiowa.

How long was his arduous journey? Some say several weeks, others several months. He was met at the fort’s gate with shock and disbelief; the return of a man believed to be dead and buried, a revenant. He sought out the youth (“Bridges” or Jim Bridger?) who had abandoned him. As the young man quaked with guilt and remorse, Glass decided not to kill him, allegedly saying: “Go, my boy–I leave you to the punishment of your own conscience & your God….but don’t forget hereafter that truth & fidelity are too valuable to be trifled with.”

The older man, the real culprit, Fitzgerald–who still possessed Hugh’s rifle–had gone to distant Fort Atkinson. Some say Glass spent only a few days at Kiowa before joining a group headed for Atkinson. Others say he spent the winter recuperating and departed in the spring. En route, the men stopped to camp. Glass went off to hunt for food and was barely out of sight when a band of Arikara attacked, killing every white man present. Once again Hugh had defied the odds with an improbable, or spectacularly fortunate, escape from death.

When he finally encountered Fitzgerald, who had enlisted and become a soldier, Glass could not take revenge without Army reprisal, so he only chastised the man for his “shameful perfidy & heartless cruelty–but enough….Settle the matter with your own conscience & your God. Give me my favorite rifle.”

How much of this is actually true? The bear attack and subsequent abandonment seem reasonably well documented, but beyond that, was Old Hugh mainly a spinner of tall tales (like most mountain men of the day), fabricating the many implausible escapes and freely elaborating on his adventures? And how much did the several original “reporters” of the Glass story bend, embellish and fictionalize to make a more dramatic yarn, one ripe with great American values such as courage, grit, self-reliance, prowess, an indomitable spirit–and even, as a capper, forgiveness with a moral lesson? We will probably never know the answer to these questions. But whatever the actual truth, the tale has proved too poignant and arresting to dismiss. Hugh Glass has become a permanent American legend.

And what of the man himself? In the early spring of 1833, nearly ten years after the bear attack and the survival trek that would make him famous, “Old Hugh” ventured out with two companions to trap beaver below Fort Cass, near the junction of the Bighorn and Yellowstone rivers. As the men were crossing the ice they were attacked, killed, and scalped by a large war party of Glass’s longtime enemies, the Arikaras.

Author’s Note: For much more detail about the Glass story and legend, see historian James D. McLaird’s excellent book, Hugh Glass: Grizzly Survivor (South Dakota Historical Society Press; 2016). For maps, informational articles and access to the original accounts of Glass’s ordeal, visit hughglass.org.