In search of tundra grizzlies on Alaska’s North Slope.

It was just after two o’clock in the morning, but in the high latitudes of the Arctic, darkness had not fully fallen. Sitting on a knoll a hundred feet above a nameless river that rushed through the gray, treeless tundra, I scanned the empty landscape while raindrops filled the eyepiece of my spotting scope.

“What do you think?” I asked my nineteen-year-old guide, Geordy Pine. Though young, Geordy has spent much of his life in remote corners of the Alaskan bush and his depth of knowledge of Arctic game exceeds that of hunters twice his age. I waited for a response while he sighed and looked up from his own spotter.

“It’s getting dark, and this rain and fog isn’t helping.”

“Should we get the others or leave them?” The plan had been to watch for game around the clock since we’d been delayed for a day and a half in Fairbanks and lost that hunting time, but the weather conditions were making glassing futile.

The whole hunting party was wet and tired. We’d let the others sleep and check the weather again at four o’clock. If the rain had stopped and the fog lifted, we would resume glassing for bears. If not, we’d wait until later in the day.

Into the Arctic

The spike camp from which we were glassing that foggy night was in one of the most remote regions of North America. We were on Alaska’s North Slope, north of the Brooks Range and 160 miles upriver from the nearest airstrip. The region is comprised of short-grass tundra that stretches from the town of Point Hope on the Chukchi Sea three hundred miles to Prudhoe Bay and beyond, a huge tract of land with few human inhabitants. Much of the landscape is dominated by hills covered by cottongrass tussocks and braided rivers, and in eons past the whole region was covered by a shallow sea. Because of this, the ground of the North Slope is rich in oil and natural gas deposits—50 billion barrels worth of which had been extracted by 2005—and the steep, rocky cliffs that border the rivers still hold fossils of prehistoric beasts.

Great beasts still roam this remote, roadless wilderness. Herds of shaggy brown muskox thrive here, and each fall the Western Arctic caribou herd migrates across to the Brooks Range in the south. Wolves are more common and more frequently seen on this wide-open tundra than in forested habitats farther south, and the tracks of Arctic grizzlies are commonly seen on the sandbars along the river channels.

Grizzlies were what brought us to the area, but getting so deep in the Arctic is no easy chore. After our delay in Fairbanks, four of us—Tom Beckstrand, Shawn Skipper, Neal Emery, and I—flew north to an airstrip and loaded our gear into two rubber rafts with jet motors for the ten-hour ride upriver to base camp. The base camp was set on a large gravel island in the river and consisted of three sleeping tents and one dining tent, and from that isolated location we could fan out even deeper into the wilderness. Rafts were the primary form of transportation, but much of the hunting required hiking to the peaks of the low hills and glassing the tundra for hours.

Arctic grizzlies are smaller than their coastal cousins, with big boars weighing between 600 and 800 pounds. And while the bears are relatively abundant in this remote corner of the Arctic, finding them on the open tundra is challenging. Dense shrubs grow along the rivers, and sometimes these shrub thickets stretch for miles. Bears use this cover for concealment, and finding them requires lots of glassing and substantial luck.

The morning after Geordy and I had glassed the ridge, the rain stopped and the veil of fog lifted from the river valley. By 9 a.m. I returned to my post on the hill to glass for game, keeping watch over the open tundra to the southwest of the camp. The night before we had seen a couple of caribou far across the tussocks near the base of another hill, but there was nothing moving that morning.

Shawn Skipper climbed up the hill to relive me and he told me that we were packing up our spike camp to move deeper into the Arctic in search of bears. He also gave me breakfast, which consisted of a Clif bar (I’d missed the morning meal of oatmeal). Following Shawn were Tom Beckstrand, Geordy, and a second guide, Randy.

Tom said he’d already packed my things and broken down my tent, which was a relief. This far from any assistance, we had to work as a team. The unpredictable weather, unrelenting mosquitoes, unreliable animal movements, and a near-total lack of luxuries could easily have resulted in a lot of grumbling, but our group, including our guides, worked hard without complaint. The bears were here—we simply had to find them.

I headed down the hill and found that, as promised, my gear was packed. The tents were folded and had been carried to the rafts, and the last of the gear was being hustled down to the gravel bar. Because of frequent changes in the weather, it was crucial to keep rain gear handy (rain fell in cascading plumes across the tundra every day, sometimes missing us, sometimes settling in directly above us). I was sorting through my pack to find my raincoat when I saw Tom running down the slope.

“Bear, bear, bear!”

I dropped my raincoat and ducked behind a screen of chest-high willows on the riverbank. Tom watched the opposite bank while he chambered a round in his.338 Winchester Magnum, and I remained hidden behind the willows with my binocular and scanned the opposite bank. By then, Geordy, Shawn, and Randy had also made it to the shore beside us and all of us were looking in the same direction.

“There it is,” Randy said as Tom set up on his shooting sticks. Neal also said he saw the bear. I peeked higher over the branches of the willows, but could see nothing.

Finally, I saw the bear on the edge of the willows across the water. The grizzly emerged from the willows on the opposite bank, its heavy shoulders rolling under its massive hump of muscle. Silver tips on the bear’s chocolate fur highlighted every powerful movement. Its broad head swung a little side-to-side as the grizzly worked its way toward us across the river, closing the distance.

The bear finally stopped and lifted its head, staring in our direction. Tom was solid on the sticks, and when the rifle cracked and the bullet struck, the grizzly dropped immediately.

We climbed into the boat and motored across the rushing water to a spit of sand upriver from the bear. There had been no sign of movement since the shot, but with grizzly it’s far better to make a careful approach and ensure that the bear has expired. But Tom’s shot had been well placed, and he had his grizzly.

Close Range

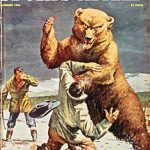

My chance for a bear came through sheer luck, and it taught me several valuable lessons regarding personal safety in the land of grizzlies. Namely, when you’re in bear country you must prepared for an encounter at any moment. Bears can appear suddenly and without warning, and they can be quite close. Such was the case with my hunt.

We’d seen a grizzly earlier that day while glassing a different section of river thirty miles from where Tom’s bear was killed. That bear was two miles or more away, appearing for a few seconds on the edge of a patch of shrub willows that probably covered thirty acres. Digging the bear out of that would be difficult, and odds were that we couldn’t approach without spooking that grizzly.

We decided to move, and chose a low hill close to the river as a vantage point. That hill was separated from the water by about a hundred yards of dense willows. When we landed the boat, Geordy stepped out to find that the water was eight feet deep beside the bank. He had to pull himself back in the raft and reposition, and after our landing, Geordy, Neal, Shawn, and I had to fight our way through the shrubs to the base of the hill. It wasn’t a stealthy approach, to say the least.

The knob wasn’t very high, rising perhaps sixty feet above the surrounding tundra. Geordy was the first one to reach the crest, and he immediately turned and grabbed my jacket.

“There’s a bear right on the other side of this hill!”

I had my riflescope on low power, and that turned out to be a wise decision, for when I asked Geordy how far away the bear was he said, “thirty yards!” in a harsh whisper.

There’s a rush of adrenaline that accompanies any encounter with dangerous game at close range, and as I peeked over the crest of the hill, I knew things would happen very quickly. In the willows below I saw only the bear’s blond shoulder hump parting the shrubs like the fin of a shark splitting still water. The bear was moving to my left, and there was just a moment to shoot. I raised the rifle, pushed the safety forward, and when the great bear cleared the willows and paused in an opening forty yards below me, I fired.

The 225-grain bullet struck hard, dropping the big bear at once. It regained its feet and turned, and I fired again, striking the front shoulder with the second shot. The first shot had done the job, and the second had been insurance, but when Geordy had an issue with his backup rifle and the bear moved again, I fired a third shot. With just thirty yards between the grizzly and us, I decided discretion was the better part of valor.

The bear was an old boar with scars, a heavy, broad body, and a coat of blond hair that darkened to nearly black on the muzzle and legs. It was a classic Arctic grizzly hunted in the classic method, on foot in the open tundra.

When the bear was skinned, butchered, and back at base camp, we took some time to fish in the rushing waters of the river that wrapped around the island. Some believe that bear meat is unpleasant and even unpalatable, but those who know how to correctly care for and prepare bears—even Arctic grizzlies—can testify to the fact that the rich, flavorful meat is delicious when cooked properly. With bear meat chilling in the shade and the hide being prepped for the fly-out, we relaxed by casting into the shallows and bouncing spinners over the rocks.

It was hard to believe that it was nearly midnight because we could still see a long way into the distant hills. I’d never been so far away from civilization, and it was refreshing—especially as the rest of the world was suffering with the coronavirus pandemic and escalating political tensions. Perhaps that’s why hunters seek out places like the North Slope. Life is short, and there are many wonderful places to see. And in some of the most magnificent places, it’s still possible to find true solitude.

Optics for Alaska

Hunting in the treeless expanses of the Alaskan Arctic require excellent optics. For this hunt, I used Leupold’s SX-4 Pro Guide HD 15-45x65mm angled spotting scope ($1,039) on a Leupold Carbon Fiber Tripod Kit ($599.99). The setup was light enough to carry up steep hillsides on glassing missions and the Twilight Max HD light management system allows hunters to clearly see objects even in low light conditions. Binoculars are important too since you won’t always have enough time to set up a spotting scope, and the BX-5 HD 10×42 Santiam binocular ($1,299.99) I used was versatile, rugged, and just-right-sized.

On my rifle I mounted a VX-6 HD 2-12×42 Leupold ($2,079.99), a scope which has quickly become one of my favorite hunting optics because of its superb light management system, clarity, and versatile magnification range. Lastly, a good rangefinder is a must-have item, and I carried Leupold’s RX-2800 TBR/W which has ½ yard accuracy to a range of 2,800 yards. Being able to range items that far away is a bonus because it tells you just how far you’ll have to hike over tussocks to reach an animal on a distant ridge.

Leupold’s American-made optics aren’t the cheapest on the market, but they’re clear in low light and extremely rugged, standing up to the abuse of daily carry up and down mountains and frequent drenching rain. Having good optics are critical when hunting the Arctic, and second-rate glass simply won’t cut it under these conditions.

Loaded for Bear

Arctic grizzlies aren’t enormous by bear standards, with big, old boars weighing between 600 and 800 pounds. However, they’re muscular, powerful, and potentially dangerous. For that reason, I used a Savage 110 Bear Hunter chambered in the powerful .338 Winchester Magnum. The rifle is equipped with a fluted barrel and selective muzzle brake that can be turned on and off as needed, and the polymer stock and stainless-steel metalwork is designed to stand up to the harsh elements of northern Alaska, which it did.

Ammo selection is also critical when hunting grizzlies, and I elected to use Hornady’s Outfitter load with 225-grain GMX bullets. This ammo features sealed, nickel-plated cases that are able to withstand moisture and the monolithic GMX bullet performs reliably even when shooting large game with heavy muscle and bone. With a muzzle velocity of 2,800 feet per second, the Outfitter GMX bullet generates over 3,900 foot-pounds of energy at the muzzle. At 400 yards the bullet is still traveling over 2,000 feet per second and generates over a ton of energy at that distance.

Topped with a Leupold VX-6HD 2-12×42 scope, this versatile rifle setup is ideal for heavy or dangerous North American game to a quarter-mile or more, making it the ideal setup for hunting Arctic grizzlies.