Legendary PH and conservationist Robin Hurt on the future of wildlife and hunting in post-Covid Africa.

Photo above: Robin Hurt with his two beloved Bavarian mountain hounds.

The two sleeping giants arrive in square metal containers in a cloud of dust and light. At 2:48 a.m., a flat-faced Volvo crane truck ended its all-night, 500-kilometer trek just inside the gate of a 15-acre boma in the Groot Gamsberg region of Namibia. The female white rhinos aboard have completed an unlikely journey of hope and survival.

As the truck crawls to a stop, the snap and woosh of the air brakes initiate a ballet of human hands, cables, and hydraulics. Piling out of the cab, the transport crew works quickly beneath an array of floodlights telescoped above the truck. Harsh illumination spills down, casting an arc of white on the men and the boma’s grass; beyond it, all else is pitch black. Outrigger arms from the truck’s chassis whirr and extend like an alien insect to find the ground and stabilize the platform. Then, finally, the team attaches the containers by cables, and the crane gently places each on the ground beside the truck.

Three of us watch from the shadows atop a spotting bench in the bed of a Toyota safari vehicle. Mere observers at this point, we’re positioned behind and up a slight rise from the containers. The crew’s animal wrangler climbs atop a container holding what looks like a basting syringe in his right hand. He slides back a panel, and the top half of his body disappears into the darkness of a hatch on the container’s roof. The syringe holds an antidote to the sedative that followed the MD99 immobilizer that downed the white rhino cow from the Gobais region in the east of Namibia—a single drop of which would be lethal to a human.

The wrangler explained minutes earlier he would squirt the liquid into the rhino’s ear, where it would be quickly absorbed, bringing the 4,000-pound animal out of her slumber. The first sound we hear is the flexing crash of the container’s thin metal walls as the wrangler backstrokes his way out of the hatch. The rhino is awake and not happy with her accommodations. The wall slamming continues while an assistant pulls a chain to open the roll-up door at the container’s end. The door flies up with a metallic rip, and the rhino charges out into the light. She descends the ramp and spins her massive body 180-degrees to face the crane truck and the lights. Temporarily blinded and disoriented, she lowers her head and exhales in aggressive, audible blasts that press dust clouds into the light beams crisscrossing her small patch of earth. At that moment, our safari vehicle seems entirely too close and small. As she adjusts to her surroundings and weighs her instinctual options, the lights shining directly in her eyes serve their secondary purpose of obscuring the people and vehicle from which she emerged. How is it possible for an animal weighing two tons to move so fast and change directions as if she were a weathervane hit by a sudden gust of wind? We just witnessed it–African nature at its most remarkable, but at the same time deeply vulnerable.

The two female rhinos will spend ten days in the 15-acre holding boma for observation, and then released to roam freely across 20,000-acres of wilderness. Though a man renowned among clients and colleagues alike for his focus and grit, Robin Hurt was flooded with unexpected emotion, “After all the work and planning, I couldn’t believe it was happening,” he recalls.

Africa was Home

Born in London in 1945, Hurt’s life began amidst the turbulence of World War II. Running the gauntlet of German U-boats on a steamship from Mombasa, his father, Roger, and mother, Daphne, sailed around Cape Horn to England. Hurt’s father, a Lieutenant Colonel in the British Army, was recalled to London to receive the Distinguished Service Order from King George VI of England. Daphne was a Kenyan of British ancestry and gave birth to Robin while German buzz bombs rained down on London. Shortly after the end of the war, Hurt’s father accepted a position in the Kenya Game Department. Kenya was then a colony of the British Empire.

Reared on the shores of Lake Naivasha, Kenya, northwest of Nairobi, Robin began his education in the African bush almost at birth. Though educated in British-modeled boarding schools, a connection to the bush and the difficulties of undiagnosed dyslexia left him constantly distracted from his classwork by what lay outside the school walls. As a child, he spent most days around the family farm exploring with his Maasai friend, Tinea.

Young Robin wanted to hunt, but his father was strict with firearms, only allowing Robin to carry a rifle on his own when he could prove to be safe and proficient. At age 8, Robin received his first rifle, a .22 caliber Krico. When he grew large enough to handle its weight and recoil, his grandmother, a woman of Kenyan settler stock and nurse in World War I, allowed him to shoot her .256 caliber Mannlicher at targets. When Robin was 12, a rampaging leopard killed twenty sheep, mauled a farmworker, and snatched his grandmother’s Jack Russell terrier off the veranda. Late one night, Robin heard growling outside his bedroom window. The leopard had returned and was twenty yards from the window—surrounded and slashing with razor-sharp claws at the farm’s baying dogs. Robin retrieved the .256 from under his bed, loaded it, and crept back to the window. Opening the window as quietly as possible, he could see the leopard in the full moonlight. As soon as the circling dogs left space for a shot, he fired from inside the house. The big cat immediately jumped and ran into the shadows. Hearing the noise, his grandmother burst into his bedroom, thinking Robin had accidentally fired the rifle indoors. Robin explained he had aimed carefully but was unsure of the shot. His grandmother wisely decided they would investigate in daylight rather than pursue a wounded leopard at night. Robin’s aim was true. They found the leopard stiff and dead 100 yards from the house, and his life as a big-game hunter had begun.

Over his father’s objections, 18-year-old Robin carved a path away from the family’s tradition of a Sandhurst education (the UK’s West Point) and a military career. He elected instead to become a licensed Professional Hunter (PH). Not merely a permit to guide clients for money, an African Professional Hunter license requires both a multi-year apprenticeship and passing a series of exams that cover game identification and hunting techniques, field medicine, firearm safety, and ecology.

Hurt spent weeks in the bush with his father’s Kenyan game scouts throughout his youth. But his formal training began via an apprenticeship with Kenya’s top Hunting Safari company, Ker Downey and Selby (KDS). At KDS, Hurt learned from a legacy of experience that stretches back to the late nineteenth century. One mentor, Harry Selby, made famous to American readers by Robert Ruark’s book, Horn of the Hunter, was himself mentored by Philip Percival, the PH who guided Theodore Roosevelt and Ernest Hemingway.

Over the next several decades, Hurt and his clients explored his native Kenya and neighboring Tanzania and more exotic regions such as the Sudan and Zaire. At that time, the areas were largely undeveloped, and warfare between rival tribal factions could and often did break out. His reputation grew as an intensely focused PH whose clients found the largest animals. Among many awards, he won the Shaw and Hunter Trophy in 1973 for a 54-inch buffalo hunted in Lolgorien, Kenya. Hurt was also the featured PH in George Butler’s documentary, In the Blood (1990). The film traces the steps of Theodore Roosevelt’s famous 1909 safari chronicled in his book African Game Trails. Joined by Theodore Roosevelts IV and V but told through the eyes and narrated by Butler’s teenage son, Tyssen, the film chronicles the family tradition of hunting and examines issues facing African wildlife. The film also features quotes and vintage film clips of then former-President Roosevelt’s safari and a shooting competition with his Holland and Holland .500/.450 Nitro Express double rifle on loan from the Smithsonian Institute and reconditioned for use in the film.

Not always glamour and adventure, the life of a PH and the safari business can be costly and sometimes deadly. When hunting in Zaire (now Congo), Customs officials extorted Hurt, refusing to return a large sum of money held as a surety on his safari vehicles and equipment. The state-sponsored theft resulted in a painful financial loss for the season and the return of deposits to nearly 20 clients whom he could not take on safari. The monetary damage forced Hurt to sell his home in England to cover the losses. Hurt was also severely mauled by a leopard in 1992. Nearly 200 pounds, the high-altitude leopard was significantly larger—both in tooth and claw—than a typical cat of that species. In less than 30 seconds, the leopard put 32 bite holes and two massive claw wounds into Hurt. The mauling crushed his right elbow and severed a large vein in his left leg requiring multiple daily scrubbings to disinfect the wounds. Over more than five decades in the African bush, Hurt has seen many close friends and fellow Professional Hunters killed by dangerous game, poachers, and the accidents that befall those who operate far from modern medical facilities.

But throughout Hurt’s extraordinary life experiences and fifty-nine seasons as a Professional Hunter, one element has remained unchanged—his commitment to supporting and protecting Africa’s wildlife and wild places. “When I began my career as a professional hunter at the age of 18 in 1963, Africa was a sea of wildlife with islands of people. Today, we have the exact opposite. Africa is islands of wildlife facing a tsunami of people.”

In 1990, Hurt founded the Robin Hurt Wildlife Foundation (RHWF) to develop linkages between Tanzania’s sustainable utilization of wildlife, poverty alleviation, and the maintenance of healthy ecosystems. The program, funded by hunter-conservationist money and ideals, turned poachers into anti-poachers by engaging and supporting the local communities to become better stewards of the natural environment. A commitment shared by the family, Hurt’s two sons, Roger and Derek, now run the Tanzania company as well as Foundation.

In addition to the support of wildlife, the RHWF takes a holistic approach to community engagement. Over the past fifteen years, the Foundation has donated over $3.2 million building 37 schools, 75 houses for teaching staff, and 28 health dispensaries in addition to numerous water pumps, and other life sustaining equipment such as tractors, milling machines and ambulances. More than bricks and mortar, the facilities train and educate the citizens on the value of conservation and the sustainable utilization of wildlife.

Recognizing the critical nature of poaching’s impact on the rhino population across Africa, Hurt’s wife, Pauline, concluded the best way to protect them was to create an organization to help “spread the risk” by moving the rhinos from areas of high concentration near human populations to more remote locations. The rhinos would then freely roam and multiply, protected by professional game guards and hunters away from poaching pressure and human encroachment. From Pauline’s original idea, the Hurt’s leveraged their contacts and influence to found Habitat for Rhinos in 2014. They raised funds to secure concessions and relocate rhinos to their ranch in Namibia. More were added over time, to include a mature bull, “Big Daddy,” who has sired more babies, including two in 2021, bringing the total to eleven. Pauline’s son, Daniel Mousley, is a professional hunter who works with Robin in the Namibian safari operation alongside the rhinos.

The rhinos on the Gamsberg Concession will not be hunted. The long-term goal for the program is to build the herd and ultimately relocate select rhinos to other remote locations managed by like-minded people committed to protecting the critically threatened species. Two full-time anti-poaching guards protect the animals. The guards track the animals daily and scout for signs of human intrusion. Support for the care and protection of the rhinos comes from the proceeds of plains game hunting on the property and donations from hunters. The Hurts also host photographic safaris and tracking the rhinos has become increasingly popular. In addition to protecting the rhinos, Habitat for Rhinos employs numerous locals that support paying guests and the ranch’s facilities.

At the 2020 Dallas Safari Club Convention, the Hurts received the prestigious Capstick Award, in recognition of the success of Habitat for Rhinos, for “long-term support and commitment to our hunting heritage through various avenues such as education, humanitarian causes, hunting involvement, and giving.”

Hurt on The Future of Wildlife and Hunting in Africa

At 77, Hurt retains the visage of a lifetime in the sun and carries himself with the same dignified bearing and direct, precise speech that keeps his clients focused and junior PHs on their toes. I recently spoke with Robin to get his thoughts on the future of African wildlife in the post-Covid environment.

Len Waldron: In a recent speech at the International Council for Game and Wildlife Conservation (CIC), you said Africa is on a cliff edge. Could you explain your thoughts?

Robin Hurt: It’s African wildlife that is on a cliff edge, not Africa itself. The reason I say that is because we have all this negative hunting information being sent around the whole world on the internet. It goes viral. Look at Cecil the Lion; most of that was a misunderstanding. So that’s why we live in such a dangerous time as far as the future of wildlife goes. All this anti-hunting sentiment is based on emotion—it’s not based on realism or science. And that is dangerous because if you stop hunting, like what’s happened in Kenya, the wildlife populations go down. If people do not benefit from wildlife, they will not keep it. It’s as simple as that. Recently, I wrote to Minister Goldsmith in London about this proposed ban on trophies coming into the UK. I said, “If you do this, you are signing a death sentence on wildlife. For example, on places like ours where currently we have wildlife, it will be replaced with domestic animals like cattle, and they are the biggest polluters on the whole planet.” So, I asked, “What do you want? Do you want wild animals roaming there, and we benefit, or do you want domestic animals there?” That’s really what it boils down to. The wildlife will survive forever, provided people benefit from it. But the minute people stop benefitting from wildlife; it becomes cheap meat or a nuisance. If someone’s grandmother is out collecting firewood and killed by an elephant, what are they going to do? They are going to kill it. But if that elephant is a valuable asset, they will think twice about killing it.

You cannot make the whole of Africa into a huge national park. Period. And most of the wildlife actually occurs outside the national parks. It’s those animals that are on the cliff’s edge right now.

Len Waldron: You’ve spent a lifetime supporting the conservation of wildlife. When was that ethos instilled in you?

Robin Hurt: I grew up with it. My father was a game warden. It was mainly from my dad, but also his game scouts. All my early hunting I did with his game scouts.

Len Waldron: What do you think hunter-conservationists have done best?

Robin Hurt: That is a very good question. To be honest with you, I don’t think we have done enough to promote what we do. That’s why in my speech last night (accepting the Capstick award), I said it’s time we put aside these differences with anti-hunters and get together and talk about conservation—and find a middle road. We can’t be at loggerheads the whole time because that is bad for wildlife. I believe in working with people rather than against them. The biggest problem is that some people don’t want to listen, even if you have all the facts. But I take the time to talk with people. I’ve talked to people who are so dead anti (anti-hunting), and then after I have explained that I am a manager of wildlife and not a killer of wildlife, they begin to realize.

I am really adamant that this term “trophy hunting” has got to stop. We don’t go hunting just for the bloody trophy. And I use the word “bloody” because that is the result. We go hunting for the chance and the chase, for the camaraderie, for being up close and personal with dangerous animals—it’s not just to hang something on the wall. The trophy is a treasured memento of all those things. We are not communicating well with people who do not understand hunting. We are managers of wildlife. The term ‘hunt’ has become a nasty word. We are perceived to be evil people. Another problem is that antis are humanizing wild animals–we use wild animals to live on.

Regarding poaching—there is a lot of misunderstanding amongst the general public in defining poaching and legal hunting. It’s a common mistake to place both under the same umbrella. A poacher is the illegal, un-selective user of wildlife—simply a thief bent on the extermination of wildlife for a quick reward. The legal hunter, on the other hand, is the legal steward and manager of wildlife. His or her very existence and way of life depends wholly on healthy wildlife herds and their sustainable use—a use set by careful management quotas.

It is not legal hunting that has led to the decline in elephant and rhino numbers. It is entirely due to unchecked commercial poaching fueling the demand for these illegally obtained products.

Len Waldron: Is there an a-ha moment when speaking with anti-hunters that you find some begin to understand an alternate point of view?

Robin Hurt: Yes, it’s very simple. They have got to understand that if you take hunters out of the bush, there is no income coming into those places, and people are not benefitting from the wildlife, so they won’t keep it. There’s not much difference between a farmer who farms cattle or sheep and a hunter that looks after wildlife. They are both managers–some people choose to manage domestic animals, I choose to manage wild animals.

Len Waldron: We were there together when the first rhino came out of the container onto your property. For me, it was a surprisingly emotional moment. I remember it vividly. Can you describe what was going on in your heart and mind when you saw it, having seen what has happened to rhinos over most of Africa?

Robin Hurt: It was a hugely emotional moment. I could hardly believe that this had actually happened and that we had been responsible. We did it to give back. I have earned my entire livelihood my whole life through hunting and the use of wildlife. So, we want to give back. We give back in many ways through our community projects and now with the rhino projects. If I didn’t have the love for the animals, I wouldn’t do it. And that’s what a lot of anti-hunters don’t understand. They say, “how can you love an animal and, at the same time, kill it?” But it’s the same with a shepherd or a cattle herder—he loves the animals, but he uses them.

Len Waldron: What have the rhinos taught you since they have been on your property?

Robin Hurt: They’ve taught me lots of things. First, I’ve always known they were extremely dangerous animals, but I didn’t realize how far they move in a night. They walk 15-20 kilometers a night, huge distances. And that’s the way they are. If you are following tracks the next day, you are following tracks that might be six or seven miles from the rhino. Also, the births are geared mostly towards male calves because the males fight and kill each other for the right to breed—so we are hoping for some female calves in the future.

Len Waldron: What do you think the most critical steps are in the next several years for African conservation?

Robin Hurt: The biggest threat we have is too many people. The big difference between my boyhood in Kenya and now is we had islands of people surrounded by wildlife. Today, we have the exact opposite—islands of wildlife surrounded by people. And that’s becoming a tsunami of people drowning those islands of wildlife. And that is why it is so crucial that people benefit from wildlife.

Len Waldron: 2023 will be your sixtieth season. If you were talking to your eighteen-year-old self, what would you tell him?

Robin Hurt: When I got my license (Professional Hunter) in 1963 at the age of eighteen, a lot of my mother’s and father’s friends said I was crazy to pursue this—there was no future in it. That was 59 years ago. I say to young people—there is a future in it. Do things properly and do it ethically. Do not do any of the canned hunting that goes on. Do not do any put and release hunting. Hunt naturally and hunt ethically. And if you do that, you’ll always have it. And again, take time to talk with people who don’t understand hunting.

Len Waldron: How as the Covid pandemic impacted African hunting and wildlife?

Robin Hurt: Covid has had a terrible effect on the entire safari industry. For most operations, this has meant 18 months of no work, and most of the hunters returning are cancellations from before. But the demand is huge, and people are returning. We managed to keep our employees and focus on improving our operations and property. We chose to pull in our horns and focus on improving our operations and property. Others were less fortunate, especially if they had debt to carry.

As for the wildlife, it is good if not better. We didn’t see an upsurge in poaching—it remained the same as before. In Namibia, we have seen consistent rains which have changed the landscape after several years of drought.

Len Waldron: You have a third book coming out. Tell us about it?

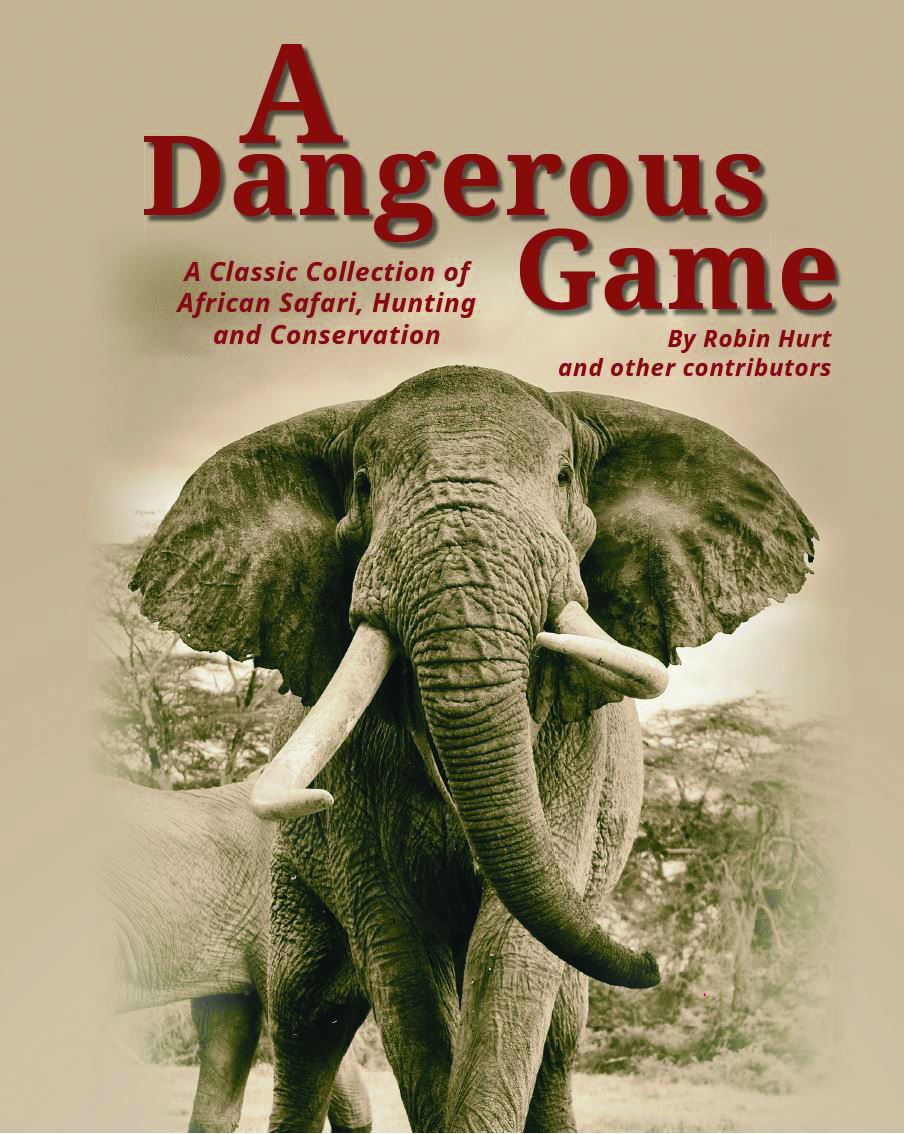

Robin Hurt: Its title is A Dangerous Game; it’s a large book featuring over forty guest writers and my own stories covering the hunting of dangerous game in Africa. The stories are first-hand accounts and images going back to the early 20th century and many untold stories such as early hunting in the Central African Republic.

Robin Hurt’s second book A Hunter’s Hunter, was released in January of 2020 by Safari Press. His third book A Dangerous Game, is set for release at the 2023 Dallas Safari Club Convention. Click here to order it.