At seventy, should you look back upon your “lasts?” or plan your “nexts?”

Photo above: Every hunt that leaves you with a multifaceted memory is a successful one. And there inevitably comes a time when there will be more memories than hunts. (c)Trail’s End Media

With apologies to William Shakespeare and his “seven ages of man,” I have my own list.

Mine starts with nineteen, when we arguably become men—women, of course, become women far sooner—nineteen is the ideal age for, according to the late poet-novelist-hunter Jim Harrison, a poet or a warrior. Twenty-one is, well, twenty-one. Twenty-seven lives under the shadow of all those who died at that age, an uncanny percentage of rock ’n’ rollers: Hendrix, Joplin, Morrison, Cobain, Winehouse. Thirty-three carries its own scriptural omen. That takes us to forty, the old age of youth or the youth of old age. Fifty is simply more of the same, except the mountains are, in general, growing steeper.

Sixty-five is a watershed, the twenty-one of senescence, when you believe you may have gotten away with something. Then, only a few years after, many of us realize we have escaped not a thing.

King James’s translators of the Testaments told us that the days of the years of our lives are threescore and ten. And by the time you read this, if I am still here—there being no guarantees for the span of a lifetime for any of us—that’s where you’ll find me, smack-dab up to my ears in seventy. In the abstract, with a gaggle of active, vital, and oh-so-witty nonagenarians and more than a few centenarians paraded before us—to cast shame on the rest of us for not living up to an ideal?—seventy is no longer considered so old, or a sell-by date. But it is.

“Look at me,” the old man—apparently not yet seventy—said to Robert Ruark’s boy in The Old Man and the Boy. “Here you see a monument to use. I’m too old to fall in love, but I ain’t old enough to die.”

It shows maturity to recognize that being seventy is to be aged. What is not maturity, though, is throwing in the towel.

Last fall, out of concern about the introduction of the Omicron variant of COVID into the U.S., the Biden Administration banned travel from eight southern African nations, five of them—South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Namibia, and Mozambique—holding the bulk of African hunting. U.S. citizens could still travel there, and were technically not prohibited from returning home. But travel to and from the U. S. and southern Africa was made more restricted and onerous. A friend of mine, in his seventies, emailed me that he was all set to attend a hunting convention and book his last safari. Now—what a mess!

What struck me was not so much the situation’s being a mess, but that he had settled on going on his “last safari.” Last. If it is the last cigarette or the last sequel to Fast & Furious, last is a fine word. But last joined to safari or hunt does not in any way spark joy, unless, of course, you’re a vegan or animal-rights zealot.

Last hunts happen for reasons other than personal ones, of course. At seventy, I can remember the last tiger hunts in India, and wanting to go on one badly. At the time of the hunting ban in 1972, the tiger population on the subcontinent was eighteen hundred. After more than thirty years without licensed hunting, there were about a quarter fewer of the big cats. A ban on jaguar hunting followed—as explained in a 2015 Forbes article, bringing jaguar trophies into the U.S. is banned because “the population compared to lions is next to nothing.” As a matter of fact, according to one 2018 scientific paper, the jaguar population across its range is estimated at 173,000.

Safari hunting was closed in Kenya in 1977. Big-game populations then fell there by two-thirds, and the move was apparently judged by the government to be such a rousingly successful conservation strategy that the ban has been extended to bird shooting, too.

Californians voted out licensed cougar hunting in 1990. It is against the law now to bring back to that state even a mountain lion taken legally in another. The wildlife authorities in California today approve more than two hundred depredation permits a year for the taking of cougars that are preying on livestock—far more than the number of hunting licenses that would have been issued. And in China, which once had an exceptional variety of big game, hunting by foreigners has been closed for almost twenty years, and extinction threatens much of that country’s big game due to there being no legal hunters in the field to create an incentive for conserving them. Lifespans are not the only things not guaranteed. Hunting countries can vanish, as well.

In some ways, those lasts—which are out of our individual control and could conceivably be reversed—are easier to take than the kind of lasts that were meant by my friend and his final safari. At seventy, I see my own lasts.

I am not yet ready to give up the hope of going back to Africa, or to stop pursuing deer, pronghorn, or elk. I could hunt another black bear, but I have taken enough. Another grizzly or brown bear hunt is probably no longer in my future, although polar bear, even if I cannot return with the hide, still has—for an agglomerate of personal reasons—a shaving of hope. I know I will never again climb a sheep mountain, or run with hounds giving chase through the woods. I might hunt from an elevated box blind or hochsitz, but I may never again use a climbing stand.

I grow old; I grow old. But it’s not about wearing the bottoms of my trousers rolled, but of learning to strike a balance, to know my limitations. Not every type of hunting was always open to me; it’s just that now there are fewer. I simply have to pick and choose more judiciously these days. And I can live with that.

I can because I began building memories early, by taking chances. Nobody hunts in Kenya any more, but I risked more money than I should have and hunted there, meeting black rhino in the wild because I went there when I did. The same with China. Just four years ago, I saw the way Burkina Faso could be and is no longer.

I slept out in the Idaho snow with the riding-mules’ hobbles clanging in the dark. In Canada, I watched the biggest whitetail I ever saw slowly cross an old logging road only yards from me and was so excited that I forgot to let off the safety as it dissolved into the forest. Glassing for mule deer on a peak at the edge of Yellowstone, I saw a grizzly sow and her half-grown cub, some distance away, but close enough to alter the entire character of the landscape. In the Northwest Territories, I watched another grizzly, a golden one, its fur so deep it moved in pleats, out on a tundra flat, uprooting a willow bush, probably to get at a single vole. Flying over Alaska in a Super Cub, I looked down to see a caribou cow standing still, belly-deep in a pond, a pack of gray wolves bedded patiently in a circle surrounding the water.

I saw a herd of javelina moving though the cactus across a canyon in Arizona, and when it proved hopeless to get the friend I was hunting with onto the animals—“Where?” “Right there!”—I went ahead and killed a boar with my .220 Swift. I wounded a blue wildebeest in the Waterbergs and trailed it over hot miles of ground with a dog named Jock. We finally jumped it, and Jock was on it in a blur, clamping onto its muzzle. I had to wait to take the killing shot until the bull shook the little dog off into the air. In the sunset among tall trees in the Central African Republic, I sat on a termite hill, drained, looking at the marvelous carcass of a giant eland on the ground as the tracker danced and chanted, and lions began to roar.

I have these memories not only because I was able to put myself in the times and places to find them, but because I made them–the way you frame and side a house. I carpentered them in my mind, and they last, another important meaning of the word. Many hunters seem to remember the taking of the animal, but not much else: not the light, the weather, the travel, the sounds and the voices, how it was to sleep and to awaken in a wild place, the food, the people, the friends. It is as if those hunters read the final page of a mystery and all they know about the book is who done it.

Every hunt that leaves you with a multifaceted memory is a successful one. And there inevitably comes a time when there will be more memories than hunts. I can’t tell you that you have to make any certain number of memories, because as philosopher Ortega y Gasset said, “I am I and my circumstances,” and not everyone’s circumstances are the same. And quality is very much more important than sheer quantity. I am saying, though, that while you should not be reckless, you should not be afraid to take a chance on having a “bad” hunt, at least once in a while. What’s the option—just because you think it wouldn’t turn out perfectly, not to have gone hunting at all? To have nothing to remember when memories, one day, could be all that you have left?

The other consideration is not to wait too long. The late hunting broker, Jack Atcheson, Sr., had as the slogan for his company: “Go hunting now while you are physically able,” which as slogans go is a pretty sound one. But there is also a case to be made for going when you are mentally capable.

There is a dichotomy to hunting and growing old. Geezers tend to become more hesitant about any number of things, and hunting can be one of them. The converse, though, is that the old have less to lose. Many things are paid for, children have been raised, spouses have gotten the better part of you–or they are happy to see you go, the Japanese having a saying that a good husband is healthy and far away. Even if logic tells us that we have experienced lasts, we don’t have to declare them absolutely so, ahead of time.

At seventy, I am going to do my utmost to think of nexts, to come by new memories, not merely to recycle the old. Is that being realistic? You tell me.

The rest of the Bible verse reads that if by reason of strength we can reach fourscore years, yet most of them are labor and sorrow; for it is soon cut off, and we fly away.

Not to cast doubt upon the Bible, but perhaps that is not the way it has to be, that the next ten years are to be gained solely through labor and sorrow. The only way to find that out is to live those years to the best of one’s ability. And when we do at last fly away, we will have at least carried on as long as we could, as well as we could, spreading our wings.

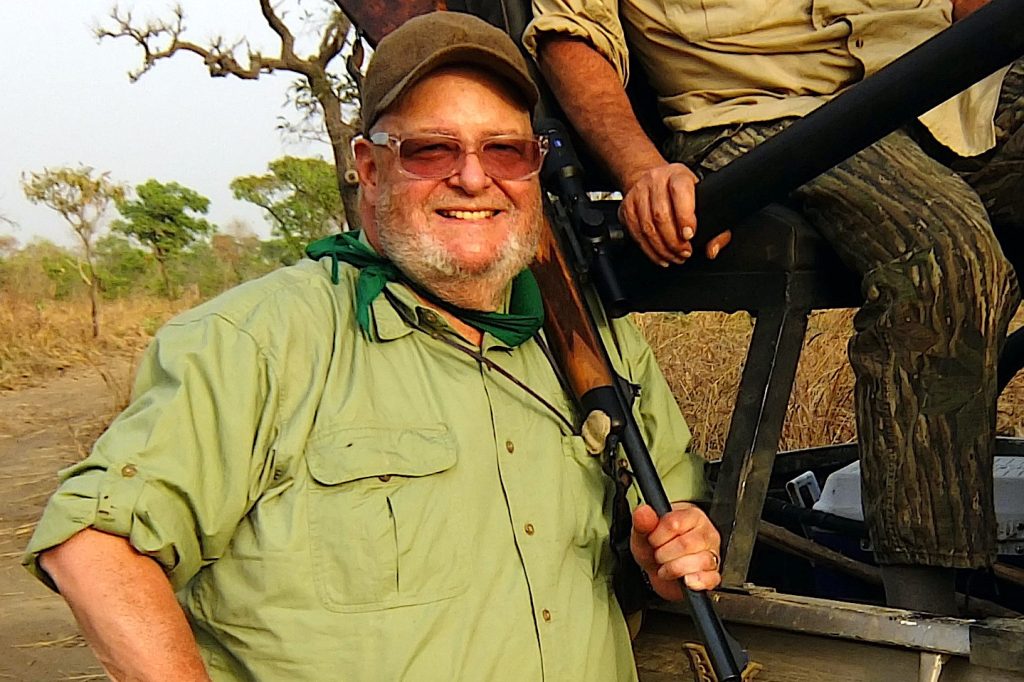

Photo by Thomas McIntyre