Does a Cape buffalo really weigh 2,000 pounds?

Photo above: PH Paul Smith, Boddington, and Wayne Holt with Holt’s awesome Zambezi Valley Cape buffalo, taken in 2005. Not weighed (as usual), this remains one of the largest-bodied Cape buffaloes Boddington has seen, and it had exceptional 45-inch horns.

One ton of black fury: so is Africa’s Cape buffalo often described. Or, if you prefer more drama, “a ton of black death.” It’s not unusual for we hunters to exaggerate the size of game animals. Nobody ever took a black bear weighing less than 300 pounds, though the actual average is a third less. Similarly, all male leopards approach 180 pounds, though an average tom is less than 150 pounds.

I’ve raised eyebrows when I’ve suggested that a big Alaskan brown bear in autumn weight could reach 1,500 pounds. All these weights are possible. North Carolina and Pennsylvania black bears have been officially weighed in above 700 pounds, and I’ve seen leopards tip good scales above 200. These are unusual, outsized animals, which occur in every species.

Lacking access to good scales, we don’t often weigh game animals, and rarely recover large animals whole, so weight is just a guess. Antlers, horns, and skulls don’t lie, which is why record books rely on those measurements. Actual weight doesn’t matter much, except that the curious among us like to know how big animals get.

Despite the legend, I have always questioned the possibility of a Cape buffalo reaching a full ton. Few are properly weighed, but I’ve seen many on the ground. I’ve always figured 1,400 to maybe 1,600 pounds for a mature southern Cape buffalo bull. No science, just experience. This is where I got my theory that an outsized brown bear is similar in weight.

As for “black death,” “fury,” and the occasional reference as Africa’s most dangerous game, there is no doubt the Cape buffalo is strong, tenacious, and can be deadly. I’ve lost friends to his tribe. Robert Ruark is credited with saying “use enough gun.” He didn’t coin the phrase; it was the title for a posthumous collection. Good advice. Ruark also wrote that he’d seen buffalo taken “as easily as a cow in a pasture with a .30-06.” Today, usually not legal, but Ruark hunted various jurisdictions before caliber minimums. Wherever, generally unwise. Let’s stick with “enough gun” as the wiser course. Combining common sense with legality, I’ve seen few buffaloes taken with light calibers. However, I’ve seen a lot of bulls succumb to a single well-placed shot.

After millennia of being hunted by lions, it seems to me the African buffalo is perpetually ready to launch. We often talk about its instant surge of adrenaline. Don’t know if that’s medically true, but it makes sense. A well-placed first shot that the buffalo is physically unable to shake off seems critical. Failing that, all bets are off. According to all witnesses, the buffalo that killed great Zimbabwe PH Owain Lewis took eighteen hits from .375s on up before giving up.

The first shot, three days earlier, was not in the right place, and we can surmise that many of the seventeen bullets that followed also were not. Even so, that’s a bunch of foot-pounds. Jack O’Connor wrote of a buffalo that took fourteen hits. I’ve never seen anything like either incident, but I’ve seen buffaloes shrug off multiple good hits. However, many more have gone down readily to a single well-placed bullet.

My rule: Place the first shot as well as possible. If the buffalo is still up and additional shots are safe and possible, keep shooting until he’s down. After that, an insurance shot is situational. If you’ve heard the death bellow and there is no movement as you approach, not always. However, I’ve heard credible accounts of a buffalo getting back up after the bellow. So, approach cautiously from side or rear, never frontally, prepared to fire again at the slightest movement.

Like all other creatures, buffaloes have different character, some more aggressive than others. A few will circle and lie in wait; others seem to prefer flight to fight. You never know, and this is more relative to attitude than to body size.

That said, the old adage “the bigger they are, the harder they fall” is probably true. If my average weight of 1500 pounds is correct, then a one-ton buffalo weighing twenty-five percent more should be harder to stop. I guess.

The American bison is a heavier animal, with large bulls averaging about a ton. The Asian water buffalo is also bigger, bulls running to 2,200 pounds and more. We know the bison’s reputation. I have taken water buffaloes on four continents. They are unquestionably larger than Cape buffaloes. I’ve seen them hard to put down, but in my experience, never as aggressive nor as quick on their feet. I wish I had experience with gaur, the Indian bison. Largest extant bovine, up to 3,000 pounds, legendary for tenacity.

I’ve never seen a gaur in the wild, nor a whole bison or water buffalo on good scales, but I know they appear visually bigger than Cape buffaloes. Regardless of species or size, all the big bovines are dangerous. It only takes one with an attitude. Just last year, the great Mexican hunter Mario Canales Sr. was killed by a water buffalo in Argentina. The smallest African bovine, the little dwarf forest buffalo, has a wicked reputation.

So do the smaller savanna buffaloes. In Burkina Faso, they take great pains to recover game whole, back to camp at max speed. There, they take weights and measurements for the game department. So, among few buffaloes I’ve seen properly weighed, I know that my West African savanna buffalo weighed 471.6 kilograms. That’s 1,037.5 pounds. The folks there told me it was a big bull. The West African savanna is the second-smallest race, and references confirm that it’s a third smaller than the southern Cape buffalo.

This little buffalo did try to live up to the reputation of its breed. It shrugged off a well-placed 300-grain .375 bullet at eighty yards, turned, and came straight in like a torpedo. He shrugged off the second, frontal shot, went down reluctantly to the third, and needed yet a fourth.

All buffaloes look big on the hoof, and big when you walk up to them. Except my one and only dwarf forest buffalo. Nice bull, fully mature. When approached, I wondered where the rest of him had gone!

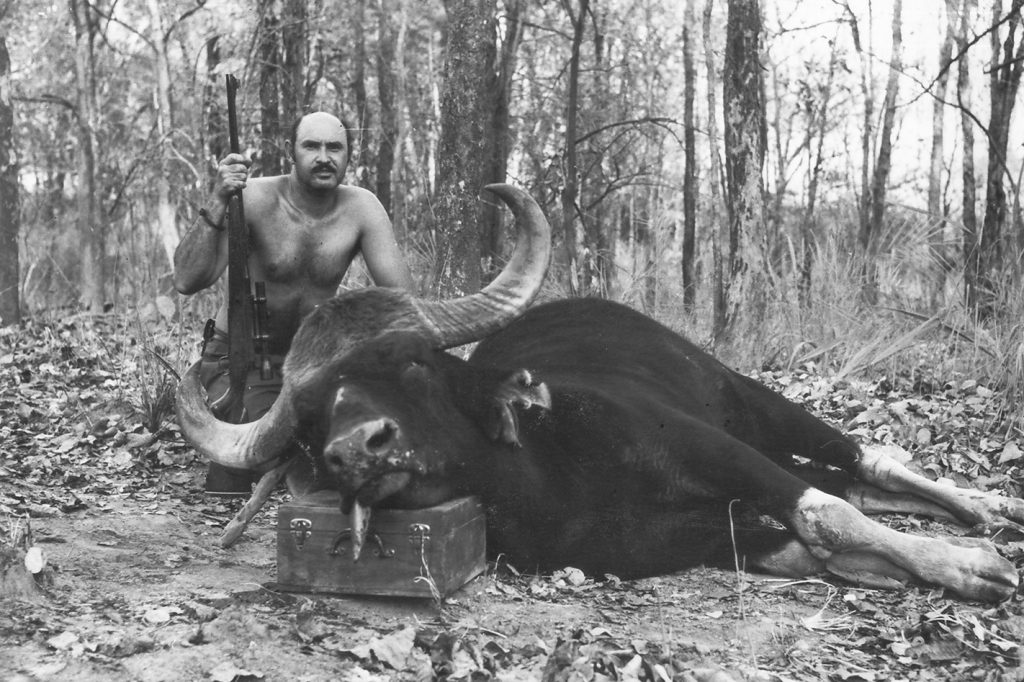

Otherwise, they all look big, dark, and menacing. For sure, some look bigger than others, and we comment, but rarely have the opportunity to weigh. My first “big” buffalo, taken in Zambia in 1984, looked like a tank, but I lacked experience to compare. After tracking two big-footed Zambezi Valley bulls for nine days, Wayne Holt’s 2005 bull was a giant in all ways: Big bosses, 45-inch spread, visually huge body. But, with no means to weigh whole, who knows?

Just now (May 2023), hunting in Limpopo with Jose Maria Marzal (Chico & Sons Hunting Safaris), my friend Jim Gent shot a wonderful buffalo. Heavy bosses, good shape, fairly wide. We guessed it at 42-inch spread, spot-on. The bull was walking alone, nothing unusual until we walked up to it. Then it got bigger and bigger, easily the biggest buffalo I’ve ever seen. Jim made a great first shot with a .375 at seventy yards, obviously hit hard but not down, so another, Almost down, back up, solidly down to his third shot. No drama, no distance covered, but a mountain of a buffalo.

All animals vary, individually and regionally. I think of the Cape buffaloes we hunt in coastal Mozambique as “normal,” whatever that is. I think mature bulls in the Zambezi Valley are a bit larger. I don’t have much experience with Limpopo buffalo. Originally, they came from Kruger, known for big buffaloes. The South Africans have been breeding disease-free buffalo for decades, so today’s buffaloes are healthy and well-fed. Stands to reason they get big, but I’ve never seen anything like this guy, visually as large as any water buffalo bull I’ve seen.

Even though he broke the winch, we managed to get him loaded whole. Nope, couldn’t weigh him, no scale big enough. In South Africa, much game meat goes to local markets. The butchery weighed the recovered meat. At 891 pounds (minus head, skin, innards, and lower leg bones), the heaviest this outlet had seen. References suggest that large bovines lose nearly two-thirds body weight from live to hanging carcass. Working the math backwards, live weight was at least 2,300 pounds.

So, after all these years, I stand corrected. An African buffalo can be “2000 pounds of black fury.” Lest anyone think super-buffalo are being bred, a couple days later I shot a good bull in the same area. Fully mature, big-bodied, horns only slightly smaller. Visually, my bull appeared “normal,” but obviously smaller. Recovered meat was 222 pounds less. Working backward again, live weight would have been possibly 1,600 pounds, about what I’ve always considered normal for a big-bodied southern bull.