He may be common, but he’s one very classy antelope.

Thanks to Chevrolet, the impala is probably Africa’s most recognized antelope. Reddish tan, with white underparts and attractive lyre-shaped horns, the impala is a classic and classy little antelope. In much of East and Southern Africa the impala is the most common antelope, and for many of us he was our first African animal, treasured forever as a shoulder mount. Usually available, plentiful, and inexpensive, impalas will feed the camp, provide baits for your leopard hunt, and offer many hours of great hunting.

Of course, that depends on where you are. In East Africa, impala don’t occur west of Uganda, and in that area kobs are the most common antelopes. In Southern Africa, it depends on the habitat. Typically creatures of dry thornbush, impalas don’t occur in true desert, so in the Kalahari, Karoo, and Namib deserts, the most common antelope is the springbok. Apparently, impalas also don’t like country that’s too wet. When I first hunted coastal Mozambique, I was surprised that impala were rarely seen. There, the common reedbuck is the most common antelope.

Although not found everywhere, the impala is one of Africa’s most widespread antelopes. Scientifically, he is Aepyceros melampus, just one species within that genus. His English name came first from Tswana in 1802, palla or red antelope. Impala comes more directly from Zulu, mpala, first used in English in 1875. Science has identified possibly six subspecies, not all substantiated. Across their huge range, we hunters identify just three races: East African, Southern, and black-faced or Angolan impala. In the British lexicon, males are usually referred to as rams.

The primary difference between East African and Southern impala is horn size. The East African impala averages larger in body, but at their best, horns pick up where Southern impalas leave off. Horn length of 24 inches is always exceptional for Southern impalas, while big East African impalas can go up into the high 20s, occasionally beyond.

Record books have to draw a line somewhere, so we reckon the East African impala ranges as far south as the Selous Reserve. I suppose. Impalas are common in the Selous, but are rarely large in either body or horn. Even in Tanzania’s Masailand, big impalas are scarce. Over the years, by being within their designated range, I’ve shot several impalas that were classified as East African. However, the only impala I’ve ever taken that was big enough to be a proper East African impala came from Kenya on my first safari. With Kenya now closed to hunting for 47 years, good luck on that.

Right now, the best East African impalas are coming from east-central Uganda. However, impalas are spotty in that country. They don’t occur in Karamoja in the far northeast, nor in Murchison Falls Park in the northwest, or points north. In three Uganda safaris, I have yet to see an impala.

The black-faced or Angolan impala has a distinctive black stripe running the length of its nose. Technically confined to northwestern Namibia and adjacent Angola, this impala is considered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service to be endangered, so the US does not allow importation. This ruling is unfortunate, since it reduces its value and hinders its management. Realistically, it seems a silly ruling; I’ve seen impalas with full-on black face stripes well outside of the designated range. The black-faced impala is probably the same size as the Southern impala but, combining little hunting with restricted range, the sampling is so small that hunting records suggest it doesn’t grow as large as its southern cousin. In 2011, on purpose, I shot a “real” black-faced impala, which is now mounted in Dirk de Bod’s lodge in central Namibia.

In Southern Africa, big impalas are where you find them. Like most common and widespread animals (whitetails, warthogs, roebuck), exceptional impalas are few and far between. Well-watered areas in South Africa, such as KwaZulu-Natal and the Limpopo Valley, tend to produce big impalas, but they aren’t plentiful. If you see an impala approaching mid-20 inches, you’d better take him.

If you can! The impala is a wary, nervous antelope, always difficult to stalk. The only saving grace: Impalas are highly territorial, depositing their round dung in middens. A big ram seen in a certain area will almost certainly be seen there again.

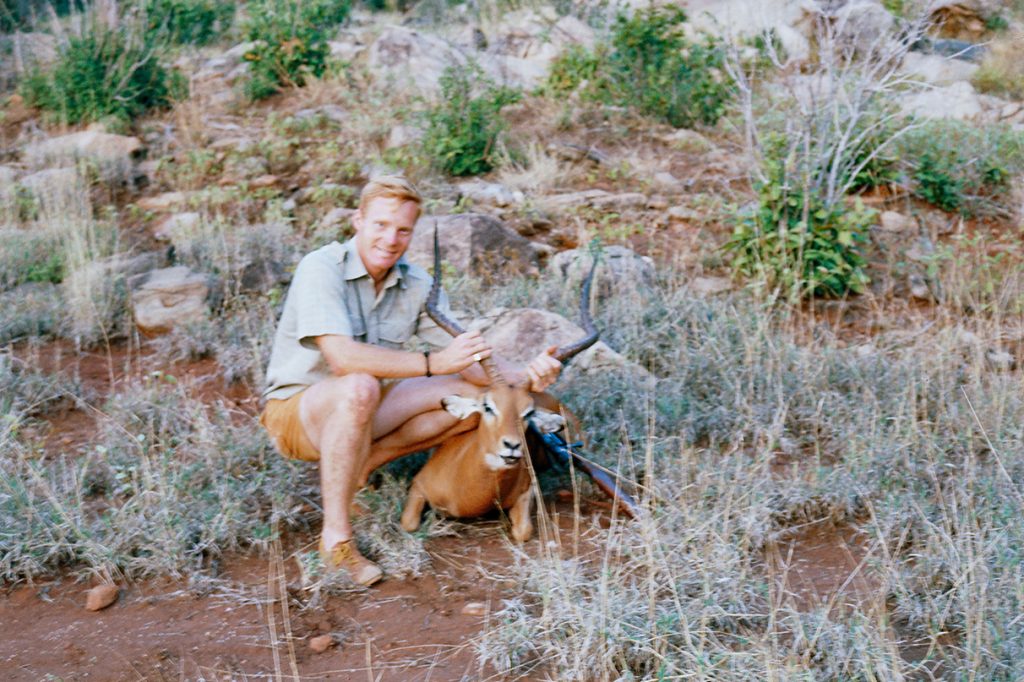

Males often congregate into bachelor herds, but a group of females will usually have one dominant male. This is probably the best opportunity to find a big boy. However, the more eyes and ears there are, the more difficult it is to approach, sort, and get a shot. My big East African impala was taken near Tsavo National Park. That area is generally too dry for the biggest impalas, and they weren’t plentiful. We’d seen this big male with a group of females and made several stalks, but there were too many animals, and it was too thick to sort him out.

On our last try, we caught them coming one at a time through a narrow opening. I focused on the gap, while PH Willem van Dyk watched them coming, tolling them off one female at a time. A tiny field of view was all I had. When Willem said, “The ram is coming now,” I was ready. I briefly saw the horns, but I was looking for the shoulder, found it, led it a bit, and pressed the trigger.

An East African impala male might exceed 150 pounds. Southern rams run smaller. Either way, they are not large antelopes. However, perhaps because they seem constantly keyed up, to my thinking the impala is one of Africa’s toughest antelopes, pound for pound. Shot placement matters with everything, but it is especially critical with impala. Hit an impala wrong, and you’re likely to have a long day. As my old friend and Tracks Across Africa producer Tim Danklef likes to say, “If impala were as big as buffalo, we’d all be dead.”

Even when you hit an impala properly, expect it to run. Back in 1988, hunting with Michel Mantheakis in Tanzania’s Masailand, I shot an impala squarely behind the shoulder with a 7mm Remington Magnum. It took off as if nothing happened and ran a solid 200 yards. We found it stone dead, after little blood. We Americans love our behind-the-shoulder lung shots. Like most African PHs, Mantheakis prefers center-shoulder shots, and he suggested I should have shot farther forward. The behind-the-shoulder lung shot is fatal, but a central shoulder shot often works faster. I’ve remembered that ever since. Given a choice, I go for the shoulder shot.

I suppose the reason impalas are so keyed up is because they are primary prey for leopards. Everything loves to eat impala venison, us included. As table fare, impala is tough to beat. I’m not big on organ meat, but fresh impala liver is mild and sweet–excellent. Although I’ve shot few big impalas, I’ve taken many average ones for leopard baits and camp meat. They are a classic African animal, and they are always great fun to stalk.