Complicated present-day realities conflict with popular perceptions. Can there really be too many elephants?

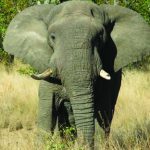

Image above: Elephants in Bwabwata National Park in northeastern Namibia.

The expression on my face in the photos afterward sums it up: still wide-eyed, slightly somber, almost confounded. It isn’t the look of a hunter enjoying what time and effort in the field has finally brought his way; an old Cape buffalo or eland would have had me smiling and perhaps relieved. But I never thought to shoot an elephant.

To a boy riveted by the tales of the old Africa hands, ivory hunting seemed the most romantic and dangerous way imaginable to make a living, and I used to wonder if I’d have the grit to confront and try to kill the largest mammal on land with a chunk of metal the size of a fingertip.

But that was then, and today I try to live in the present. Because they are social, intelligent, evidently thoughtful, and even self-aware, elephants for me abide on a plane above their fellow species of savanna and forest. I have stalked elephants until I could look at them through my sights (and whisper Boom!), but truly killing one seemed beyond the pale—never mind the crazy trophy fees. Once or twice the need to maybe shoot one in self-defense has come up, but the situations evaporated. This time, though, I was asked to do it. Or rather, I was offered the opportunity to do it and I couldn’t say no. It seemed to be a part of safari that few people experience now, and (in the absence of a veterinary team) there was a compelling reason to shoot this one.

An elephant had appeared in the meadow on the far side of the river—the Okavango, in northeastern Namibia. He moved slowly along the high bank until it flattened out and he could step into the water with dignity, and from there he angled out into the current, wading and then swimming. It is commonplace to see elephant and buffalo in that meadow, but this elephant was solitary and massive and center-stage, and he held our attention until he disappeared from the binoculars.

The next morning we came upon him a few miles away, still alone—and bedded down. The Mahango core wildlife area, in Bwabwata National Park, is alive with elephants; it’s unusual to see just one, and I’ve never seen a mature bull anywhere but on his feet. Tracker Gideon hopped off the truck and jogged toward him, clapping his hands. The elephant stood up and moved away, laboriously. In fact, he was limping, heavily favoring his right forefoot. I had to wince, watching him. Jofie Lamprecht, our Professional Hunter, grabbed eight seconds of video and WhatsApped it to the district warden.

An hour and a half later, the warden responded. Jofie studied his phone and turned to me: “Want to shoot an elephant? The warden says, ‘Take him out before he collapses.’ That’s when the vultures will arrive and the predators start eating on him.”

It wasn’t hard to find him again, or to stalk within a few yards. It is a sobering sight, an animal of that size and presence throwing up its head and crumpling to the ground. I didn’t hear the shots, didn’t feel the recoil, and can’t tell you exactly where I put the coup de grâce into the top of his skull from behind. My mind was taken up by the enormity of it all. Then there was a stillness before Jofie and Mike and Gideon and Nadila solemnly shook my hand.

People vs. elephants

A century ago, Africa was thought to have 10 million elephants. When I began to visit, 35 years ago, there may have been about 1.1 million of them remaining. Today there are, reportedly, barely more than 400,000 and everyone “knows” that elephants are “endangered.” I’ve been scolded for killing even one of them.

Yet virtually everywhere in Southern Africa that I’ve stayed has been heaving with elephants. I get to go to prime wildlife country, though, not where agribusiness, mining, or other development is going on, or even where villages are expanding into the bush and families are hacking out room for a few stalks of mealies and a herd of goats. It is elephant habitat that is disappearing—and taking the elephants with it.

Ian Parker, who became an outspoken wildlife consultant after leaving the Kenya Game Department in 1964, reminded me (by email) of some hard truths: “Jonathan Kingdon [author of Mammals of Africa, Vols. I-VI] mapped East African elephant range at three points in time—1925, 1950, and 1975. It had declined progressively by over 60 percent. In a nutshell, elephant and human distributions were mirror images of one another. At 20 people per square kilometer, elephant populations were vestigial. At 40 to the square kilometer they were gone. In 1900 the [human] population of Africa was estimated at ~140 million, today it is 1.460 billion, a 10-fold increase; elephant range has declined in similar proportion and will continue to do so for as long as human increase persists.”

Yet, paradoxically, in many of their shrinking ranges—the parks, reserves, hunting concessions, and other conservation areas, and the less-accessible corners that have not yet been hard-hit by humans—elephants are multiplying, sometimes well beyond capacity, and human-elephant conflict is intensifying, despite uncommonly high tolerance by some rural African people. Ecologists are warning us that elephants can bring their own, and other species’, demise with them. They can eat trees, after all.

The recent KAZA survey

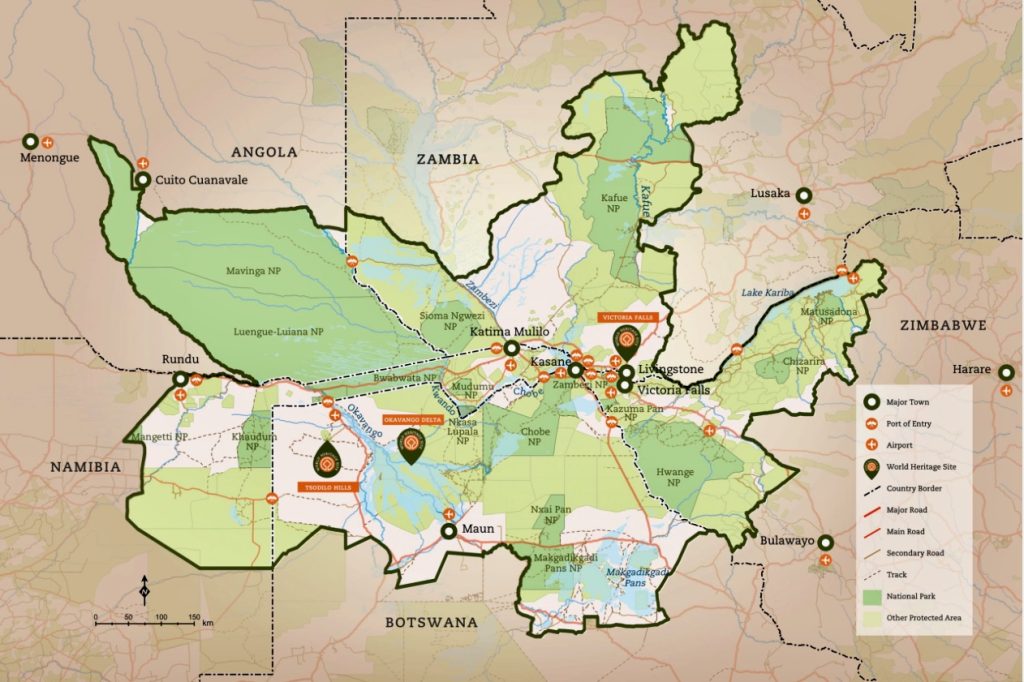

In 2022, an aerial survey of KAZA, the Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Conservation Area—201,000 square miles, 128,640,000 acres, across parts of Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe—found 227,900 elephants, likely more than half of Africa’s remnants.

Aerial wildlife surveys are notoriously difficult, especially in Africa, but this is 10,930 more elephants than were counted there in 2014-15. Is this a real increase or due to survey variations or migration? In any case, the “carrying capacity” of KAZA has been bumped up by large sums of conservation money—spent, for example, on drilling artificial water holes and opening up migration corridors—so the region may be able to sustain more elephants for longer than previously possible. However, the survey also found slightly more elephant carcasses this time; Darren Potgieter, the survey coordinator, said this would be studied, and cautioned that “factors such as aging populations, improved sampling methodologies, environmental conditions, and poaching could all be at play here.” But wildlife biologists now point to elephant deaths in KAZA due to drought and disease and to vegetation destruction, which may signal elephant overpopulation. Climate disruption surely plays a role too.

Some breeding herds and bulls migrate across KAZA, but the new survey found by far the most elephants within Botswana: 131,909. (Also 3,840 in Zambia; 5,983 in Angola; 21,090 in Namibia; and 65,028 in Zimbabwe. Yes, these add up to 227,850, not 227,900.) This is 1,970 more than the earlier survey found in Botswana—and about 120,000 more elephants than Botswana was thought to have c. 1960, when safari hunting began to develop there.

Botswana’s elephant numbers

No one knows just how many elephants Botswana actually can absorb, but in 1991 its Dept. of Wildlife and National Parks decided that “no more than 55,000 elephants could be sustained without habitat degradation” and recommended “adaptive management.” Botswana is now the epicenter of concern about elephant overpopulation, and some observers are sounding the alarm about “desertification.” Botswana’s 82-page 2021-26 Elephant Management Plan notes the “undesirable impact” that elephants can have on their habitats, and that in some areas canopy trees are being killed by elephants faster than they can re-grow, but adds that “impacts on other species, loss of biodiversity, effects on essential processes and on the ability of the ecosystems to sustain the elephants may all be disputed due to lack of evidence.”

However, “elephant-induced vegetation change” in Botswana has been formally studied since at least 1993 and probably earlier. The best layman’s discussion of the situation I’ve read is a long article (“Elephants: A Crisis of Too Many, Not Too Few”) by Dr. Brian Child that I prepared for the April 2020 issue of the e-zine Conservation Frontlines.

Dr. Child has a PhD from Oxford in wildlife and livestock economics; he grew up in Botswana and Zimbabwe, where his father was a national park ecologist and director. In short, to curb the destruction of vegetation in Botswana by elephants, and the resulting impact on other wildlife, he proposes a return to the nation’s successful and apparently sustainable commercial “conservation estate,” which from about 1960 to 1990 derived employment, revenue, hides, ivory, meat, clothing and artifacts from game—all while wildlife numbers rose steadily and elephants apparently were kept in balance. The nation has taken a step in this direction by building a $15 million multi-species abattoir in Tsabong, to support game farming and hunting. (Can it process elephants?)

Managing elephant populations

Maintaining elephant numbers is one thing; reducing a large surplus is entirely another. Ivory poaching has decreased and become almost negligible, at least in reducing overall elephant numbers; and safari hunters (Botswana may also allow “citizen hunters” to take elephants at sharply reduced fees) likely could not take off enough elephants even to blunt their average annual replacement rate of about 5 percent, much less bring present populations down to ecologically healthier levels. Foreign hunters in Botswana and Zimbabwe, where elephant numbers are highest, presently “harvest” about 500 elephants annually; simply to begin to flatten elephant population growth, these hunting numbers would have to increase approximately 20-fold.

The villagers who now descend upon an elephant kill with pangas and ecstatic cries might begin to roll their eyes and say, “What, elephant again? How about a nice hippo instead?” Trophy fees would have to drop dramatically, to put elephants within reach of more hunters, and hunting companies might see this as more work and risk for less pay—or new operators might arrive, setting off turf battles and causing problems through inexperience. The off-take could not all be bulls, either, for this would drastically skew herd dynamics. Inevitably, in some areas photo-tourists would encounter more elephant kills, with the opportunity for more social-media friction between hunters and anti-hunters.

Regardless of these market conditions, elephant populations must be managed. Botswana’s elephant plan does not mention culling. Culling is still included in South Africa’s National Norms and Standards for the Management of Elephants, updated in 2008, but to my knowledge it has not been carried out there—or anywhere else—since 1994, in Kruger National Park. From 1960 to 1991, Zimbabwe reportedly culled or hunted 46,775 elephants. Following the Trans Africa Drought of 1977-81, South-West Africa (as Namibia was then) said it culled 570 elephants to reduce pressure on black rhinos and roan antelope in especially dry areas.

Culling is not a one-time adjustment; elephant births may increase afterward because more food is available, and the need for culling becomes ongoing. Culling can be effective and inexpensive, but it does have drawbacks and logistical challenges.

Leaving tons of carcasses to rot in one spot can lead to outbreaks of disease, and heaven help the national park whose visitors come upon a charnel ground of 40 or 50 elephant carcasses, old and young, male and female, piled together and reeking in the sun. To prevent social disintegration, entire family groups are wiped out together. Selectively killing a few “problem” animals, as every elephant-range country does occasionally, is not culling in this sense; nor is generally illegal “retaliatory” killing by rural people who’ve been harmed by elephants.

In Kruger Park, in northeastern South Africa, where roads are good, the carcasses were taken in closed trucks to abattoirs that canned the meat for sale in markets. The BBC News pointed out that these contractors and distributors could not gear up for the work without some assurance it would continue—another factor in an overall culling plan. (But in Botswana, trucking elephant carcasses out of the Okavango Delta, for example, is impossible; those animals would have to be intercepted elsewhere along their migratory routes—if even feasible.)

Reportedly, the canned meat sold well. If CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, were to lift the counterproductive ban on regulated trade in elephant ivory, the economic—in addition to the ecological—incentive for culling might be even stronger.

Besides the C-word, other controls

Would it be strong enough to enable KAZA countries to shrug off the subsequent firestorm of protest by international animal-protection groups? And at least the threat of a tourism boycott? Candidly, this is what politicians and bureaucrats fear most about culling elephants—videos on social media, followed by accusations of a return to “apartheid-era” or “colonialist” thinking. In 2021, a news report that Zimbabwe’s Parks and Wildlife Authority was considering culling elephants drew instant condemnation from a group that equated culling with extinction.

So what’s a nation with too many elephants to do? Recently Namibia and Zimbabwe sold a few hundred live-caught elephants to China and Middle Eastern countries for zoos. The goal was not to reduce elephant numbers but rather to raise some much-needed cash for conservation. The animals were captured and moved under veterinary supervision, but nevertheless an international public outcry followed.

Relocating elephants in-country—away from villages, for example—has been tried too, with little success; elephants tend to return. As well, the cost is prohibitive; in 2018, Zimbabwe reported that capturing and moving 100 elephants cost about $400,000, an unsustainable expense.

Fertility control for elephants has been studied extensively, beginning with the reproductive physiologies of cows and bulls and proceeding to the social aspects of breeding among different age classes, and then gestation and lactation periods and intercalving intervals among cows. My favorite part is comparing NDVI, the Normalized Differential Vegetation Index, to fecal progesterone metabolite concentrations during estrus and in pregnancy, and how these vary in the wet and dry seasons.

Briefly, then, it’s not just a matter of darting elephants with a vaccine—which hasn’t been developed yet, or tested—from a helicopter. Even if it were, the effects of contraception on elephant behavior have not been determined. (The behavior of animals that weigh tons is consequential.) The final considerations are methodology and costs, which are, respectively, complex and high. The impacts of birth control are not immediate, either; population numbers will begin to go down only when the mortality rate finally exceeds the birth rate. A cow elephant’s gestation period is nearly two years.

Meanwhile, in Namibia . . .

To return to the nation where this story began: With respect to wildlife, and especially elephants, Namibia may be unique. Its Constitution mandates the “maintenance of ecosystems, essential ecological processes and biological diversity . . . and utilization of living natural resources on a sustainable basis for the benefit of the Namibians, both present and future.” (“Sustainable use” has become code for “hunting.” Namibia strongly supports managed hunting, for a variety of reasons.)

Not only has Namibia’s total elephant population approximately tripled, to about 24,000, since independence from South Africa in 1990, but thanks partly to the nation’s communal conservancies, its elephant-distribution range is actually expanding; no habitat shrinkage there. (Only northeastern Namibia lies within KAZA; The nation has elephants in the northwest too, which add to the 21,090 counted in the 2022 survey.)

This is not to say that elephants are not a concern in Namibia—human-elephant conflict is worsening—but that, in the second-least-densely populated country on earth, there is still room for elephants and people to prosper. And, overall, Namibia sincerely appreciates its elephants; they draw visitors.

Namibian hunting operators are presently allowed to export 93 elephant bulls per year. The nation’s 119-page National Elephant Conservation and Management Plan 2021/2022 – 2030/2031 contains but one sentence that could refer to culling: “Other ways of reducing overconcentration of elephants (lethal removal, translocation) are used as means of last resort.”

In June 2021, I returned to Bwabwata National Park, in Namibia’s Caprivi District, for the first time in 16 years. Lions roared along the river almost every night, something I’d not heard in 2005; I also saw many more elephants than in 2005. In June 2023, when I shot the injured tusker, we came across even more elephants than in 2021. This is likely coincidental; but it was clear that, in two years, more of the baobab trees had been attacked—the bark stripped away and the trunks splintered—by elephants. With their enormous canopies and root systems, their fruit and their ability to store moisture, baobabs are fundamental to the semi-arid savannah ecosystem; and they may live for centuries—if unmolested.

The lessons of Tsavo

The worst elephant boom-and-bust of modern times was the Tsavo die-off of 1970-73 in Kenya, when elephant overpopulation and drought turned 8,000 square miles of woodland into a moonscape. Poachers and native hunters as well as the drought were blamed, but the reality was that elephant “conservation” had been too successful within Tsavo National Park. According to Peter Beard (The End of the Game), “A director of the Tsavo Research Team estimates that thirty thousand elephants died there from starvation, constipation, and heart disease—all attributable to density and mismanagement.”

Concerning the evident increase in elephant numbers in Bwabwata National Park and their impact on the baobab trees, Dr. Malan Lindeque (former Permanent Secretary of Namibia’s Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism) told me that he doesn’t think a Tsavo scenario is likely there because BNP is part of KAZA—an interconnected system that enables elephants to move from the park into adjacent Angola, southwestern Zambia and Botswana. In other words, there’s still room. I didn’t ask for his thoughts on what Botswana should do with its 130,000-plus elephants.

Harking back to Dr. Child’s comments about Botswana’s “conservation estate”: By 1980, a company called Botswana Game Industries was buying hides, furs, ivory, and other raw materials from more than 5,000 local Batswana hunters and refining them into millions of dollars’ worth of wildlife products. After diamonds and cattle, BGI reportedly was Botswana’s largest revenue producer.

Ian Parker was a shareholder in and consultant to the company; in 1983, he told me, he advised management to change course: “I’d been tracking the success of the animal-rights movement worldwide in convincing a gullible public that it was ethically wrong to buy wildlife products.” Since BGI couldn’t afford an equally powerful counter-PR campaign, Parker felt it best to bow to the inevitable and switch over to processing cattle hides. But today, Parker says, African nations that heed foreign animal-rights groups and anti-hunting politicians have only themselves to blame.

A different standard for Africa

Ironically, while hunters kill enormous numbers of animals across North America, Great Britain, and Europe, some uninformed or misinformed citizens of those countries have let themselves be convinced that it is proper to demand that nations thousands of miles away cease the killing of their wildlife, however damaging, dangerous and over-abundant it may be. Is this not neo-colonialism? And did these Western countries not wipe out, or nearly, some of their own megafauna before learning basic conservation lessons?

Legislation to ban the import of hunting trophies has come before the British Parliament three times in recent years. In March 2024, six African nations sent delegations to London to protest the proposed ban on the grounds that it would reduce funding for wildlife conservation (including anti-poaching patrols to protect elephants) and severely impact people that rely on hunting for jobs, revenue, and meat.

Botswana’s Assistant Minister for State President offered to send 10,000 elephants to London’s Hyde Park so that Britons could “have a taste of living alongside elephants, which are overwhelming my country. In some areas, there are more of these beasts than people. They are killing children who get in their path. They trample and eat farmers’ crops, leaving Africans hungry. They steal the water from pipes that is flowing to the people. They have lost their fear of humans.

“Elephant numbers, just like those of Scottish stags, have to be controlled. Hunters in the Highlands pay to shoot deer and put their antlers on their walls. So why is Britain trying to stop Africa doing the same?

“Botswana is the most successful country in the world at looking after elephants, buffalo, and lions. We don’t want colonial interference from Britain.”

Well-managed hunting can be a significant component of conservation, particularly in funding and incentivizing it. Culling, or cropping—of deer, wolves, bison, and any number of invasive species, from cane toads to feral housecats, rats to mink—is routine in the Western world, and springbok, impala, and other antelope are still periodically thinned in Southern Africa. But all this cuts little ice with people who believe the best way to conserve charismatic animals is to, well, not kill them.

Killing elephants in particular has become taboo, and even many sensible, experienced hunters say they would not do it; they may grasp the need, but it’s a personal choice. Why are elephants different? We know why; I said it myself, in the third paragraph: They are intelligent, social, thoughtful, self-aware. Elephant-range states face stark choices.

About the author: Silvio Calabi is a retired publishing executive and a lifelong conservationist and hunter. He lives on the coast of Maine and in the mountains of Colorado.