South Africa is now one of the top places to find a big sable antelope.

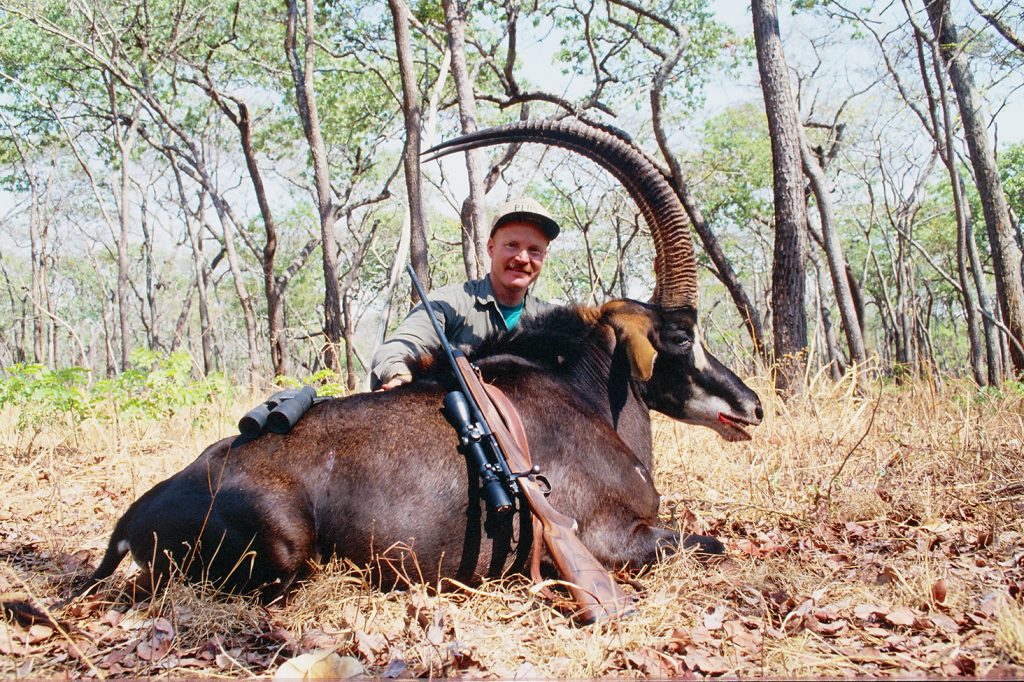

This past June, in big, brushy country in the western Limpopo Valley, my friend Bryan Pettet took one of the most beautiful sable antelope I’ve ever seen. It was 48 inches-plus on both horns, secondary growth six inches up the bases. I never thought I’d get a chance to run my hands over sable horns like that, and especially never thought it would be possible in South Africa.

The magnificent sable has always been a premier animal, for much of my career ranking just behind the Big Five in desirability and value. Hippotragus niger has a large range, from South Africa north through most of Mozambique, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Zambia, and into southern Congo; west across northern Botswana, northern Namibia, and into southeastern Angola. In the north, sables end in southeast Kenya.

The sable is an edge antelope, both a browser and grazer, typically found in savanna woodlands interspersed by grasslands. Sable are herd animals, typically a dozen to thirty females and youngsters, usually with one dominant herd bull. Males are often found singly or in bachelor groups up to a dozen. Large and dark, sables are highly visible when caught in the open, although in shadowed trees they disappear like ghosts.

I don’t consider them especially wary, certainly not to compare with the spiral-horned tribe. If you can locate a good bull, chances of closing for a shot are pretty good. However, densities vary widely and rarely are sables plentiful. Hunting them isn’t usually difficult; finding them in big country can be the real trick and, in woodlands, almost impossible. Against this, sables are somewhat habitual: A group seen in an area is likely to be seen there again. First, however, you must find them.

In 2010 I did a three-week safari in the Rungwa region in central Tanzania with Michel Mantheakis. Rungwa is one of the best areas in Tanzania for a big sable. We were trying to get Ron Bird a lion, which we did on the 21sr day. Before then, we rolled tires for countless miles, looking for tracks and hunting lion bait. We saw a lot of game, but never one sable, which was surprising.

In 2006, at Mahimba in coastal Mozambique with JP Kleinhans, we did a long filming safari. Sable don’t grow big horns there but they aren’t uncommon. Early on, producer Dave Fulson missed a fine bull. No shame, his rifle had come disastrously out of zero. We had time, expected to see Dave’s bull again and he’d achieve redemption. Weeks passed before we saw that bull again, bedded in open grass two hundred yards from where he’d been shot at.

Three races are generally recognized: Common sable (H. n. niger), most plentiful and widespread; Roosevelt’s sable; and the giant sable. The giant sable, H. n. variani, is isolated in small areas in east-central Angola. The giant sable is larger and its horns start where common sable horns end, potentially into the mid-60 inches. Endangered and protected, the giant sable has barely been hunted within hunting living memory.

Slightly smaller in body and horn, with mature bulls typically having a reddish tinge, Roosevelt’s sable is found from Kenya’s Shimba Hills south along the coast. Named in honor of Kermit Roosevelt, it was long thought the Roosevelt sable stopped in Kenya. Recent DNA research proved Roosevelt’s sable continues south through coastal Tanzania, including Selous Reserve.

Roosevelt’s sable probably progresses into Mozambique. Her coastal sables are smaller, with reddish tints. I believe Roosevelt’s sable persists at least as far south as the Zambezi, but that DNA research has not been done. When I shot “Fulson’s sable” at Mahimba, I gave myself credit for having a roosevelti, but it wasn’t technically true. Later, I shot a big sable in the Kilombero Valley, so can claim I have a “proper” Roosevelt’s sable.

I’ve taken good common sables, in Mozambique, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, and Zambia, but never a monster. Both sexes grow similar horns, curving up and sweeping back to sharp tips that sables know how to use. Males are larger in body, with horns that are usually longer and always thicker. Young sables are tan, darkening with age. Some females get very dark, but only mature bulls achieve that jet-black coat, offset by white belly and brilliant white face mask.

Sable horns continue to grow, but growth slows with age, and at some point tip wear exceeds growth. Maximum horn growth is probably about seven years. Older bulls show a smoother “secondary growth” at horn bases, below the well-defined rings. Male mortality is high from fighting; in the wild, old sable bulls are uncommon.

At full maturity, a sable bull’s horns may be just 34 inches. In most areas a mature bull with 38-inch horns should be considered good. The Holy Grail is a bull with 40-inch horns; the Rowland Ward minimum for common sable is even bigger at 42 inches. Both are tough marks to meet, depending on area. Where I hunt in coastal Mozambique, the Marromeu complex, sables have prospered, now among the more common large antelopes. The quota is large, but horn length rarely extreme. Years back, a young PH brought in a 45-incher, unheard of in that area, just one out of hundreds taken. Every year, the skinning shed sees a handful of bulls with 40-inch horns, but in this region, good mature bulls are usually in the 36 to 38-inch class. Those are nice sable bulls.

They do get bigger in some areas. Rowland Ward lists an astonishing thirty-five sable bulls of 50 inches and larger. Of these, twenty-six are recorded from Zambia. Of the rest, three from Zimbabwe, two from RSA, one from Zaire, and three of unknown origin.

Throughout my lifetime, western Zambia has been the best place for big sable. My personal best came from Mumbwa in Kafue in 1984. At 43 inches, it was a great sable. Hunting in Kafue in 1996, Bob Petersen took a huge bull. Not 50 inches but close. Wish I’d put a tape on it.

Western Zambia clearly has the genetics. However, it’s iffy. Big country with ideal habitat, sables present but not common. Not every hunter will get a monster, and many won’t see a shootable bull. Northwest Zimbabwe, especially Matetsi, is also known for big sable (one 50-incher in RW, taken in 1978). I saw gorgeous sables there back in the 1980s, but no monsters. Par for the course when hunting sable, even in great places.

RSA produced the RW world record (55 3/8 inches) in 1898, and another 50-incher in 1980. Genetics are thus present, but until recently I considered South Africa a poor choice for sable. From the late 1970s South Africa’s game ranching industry took off slowly, then accelerated like a freight train. Exceptional breeding bulls existed, but sables were found on few properties. Available bulls were scarce, quality mediocre, and prices exorbitant. Safaris have long been costly in Tanzania and Zambia. Combining availability, cost, and success, Zimbabwe was the best place to hunt sable. Then Mozambique came back, since 2000 also a good choice for a sable safari. In Namibia, numbers were similarly low and prices high, but quality was excellent. A decade ago, I considered Namibia a better choice for sable than South Africa.

South Africa’s sables were sort of like her buffalo: I missed the sea change. Under my nose, game ranchers have been hard at work for decades, breeding valuable sables for both quality and numbers. It didn’t happen suddenly, but a tipping point was reached. Sables are now widely available in South Africa, quality has increased, and prices have dropped. Right now, South Africa offers Africa’s best opportunity for a great sable bull. Yes, it’s true that most aren’t strictly free range, also true that extra-large bulls are costlier. It’s still the best and most affordable destination for sable.

In June 2024 I was hunting in western Limpopo with Jose Maria Marzal’s Chico & Sons. We were mostly hunting buffalo, with several hunters coming in sequentially. Along the way we saw sables, including one exceptional old bull. Just because I didn’t want him doesn’t mean I didn’t appreciate him. We saw him twice and took photos.

A couple weeks later, my friend Bryan Pettet took his buffalo on that property, and then he suggested he might be interested in a big sable. We knew where such a sable lived. The two times we’d seen him he was alone, and we knew he might not be easy to find. He wasn’t. But on a hot midday, we glassed down from a rimrock and there he was in some brush near a small waterhole, one of the places we’d seen him before. The stalk was on, Bryan made a fine shot, and I was able to run my hands over those wonderful horns. The fable of the sable has changed.