How a conservation-minded cartoonist helped save America’s waterfowl.

In the 1930s, the Dust Bowl was taking a tremendous toll on ducks and their habitat. Poaching, a lack of law enforcement, and draining of wetlands had been causing waterfowl populations to decline for years, and now the drought in the Midwest dried up the remaining breeding habitat. As waterfowl populations fell precipitously, sportsmen began to realize that dramatic action on the federal level would be required to stem the losses.

Ideas had been floating around for some time about how to restore duck habitat and how to pay for it. As early as July 1921, an editorial appeared in Sports Afield, advocating the institution of a Federal Hunting License for waterfowl and migratory birds. It decried the loss of wetland habitat and noted: “Surely no man who hunts migratory game birds would balk at paying 50 cents a year, the money to go into a special fund to ensure his sport…” The money, the editorial went on to suggest, would be specifically used for “the better enforcement of the Federal game laws and the purchasing of suitable marshes for public shooting grounds and refuges. With this much money available each year, the Government would be able to acquire large tracts of land for refuges, and the question of the preservation of our migratory game birds and the sport of hunting them would be settled for all time to come.”

Enter Jay Norwood Darling (1876-1962). He was born in Michigan but his family soon moved to Iowa, where he spent much of his life and became an avid duck hunter. While in college, he began signing his drawings with a contraction of his last name—D’ing—earning him the nickname Ding. Ding drew editorial cartoons for the Des Moines Register and the New York Herald Tribune between 1917 and 1949, and he won the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Cartooning twice, once in 1924 and again in 1943.

Ding’s love of hunting led naturally to an interest in conservation, which became a frequent topic of his cartoons. He was also instrumental in several conservation initiatives in his home state of Iowa, including a move to change the state’s wildlife agency from a political entity to a nonpartisan commission—making Iowa the first state to do so. In 1934, despite the fact that Darling was a staunch Republican, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him to a blue-ribbon Committee on Wildlife Restoration to study the problem of rapidly declining wetlands and waterfowl habitat. His committee came up with several ideas, but in the heart of the Depression, there was no money to fund any of them. So Ding decided to develop and expand on the federal license idea, which had been floating around duck camps for some time, as reflected in the early Sports Afield editorial.

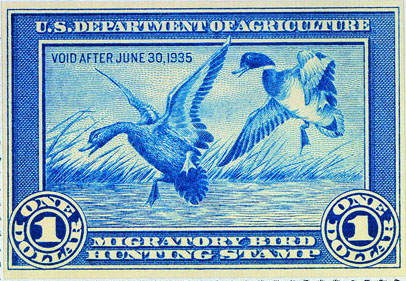

The result was the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, better known as the Duck Stamp Act. Passed in 1934, the act required anyone over the age of sixteen who wanted to hunt waterfowl to purchase a federal duck stamp in addition to the already-required state hunting license. The cost of the first stamp was $1.

A crucial part of the Duck Stamp Act was that revenues from duck stamp sales did not go into the general federal treasury—they went directly to a Migratory Bird Conservation Fund, and a minimum of 90 percent of this revenue had to be used for the purchase, development, and maintenance of refuges for waterfowl. (Today, the law requires 98 percent.)

In the ensuing eighty-three years, the Duck Stamp has been one of the most successful conservation programs the world has ever known. Since its inception, it has netted more than $800 million and enabled the acquisition of 5.7 million acres of wildlife habitat. Anyone can buy a Duck Stamp, but the majority of stamps are purchased by hunters.

Ding himself created the first Duck Stamp artwork at Roosevelt’s request, drawing a couple of mallards landing on a pond to illustrate the inaugural stamp. The yearly duck stamp competition went on to become the only art contest sponsored by the federal government. There is no monetary prize involved, only great prestige for the winner.

Even if you’re not a duck hunter, buying a Duck Stamp (they now cost $25) is still one of the best things you can do to help ducks, geese, and other wildlife.

Ding’s contributions to wildlife conservation weren’t finished just yet. He was soon named head of the U.S. Biological Survey, forerunner of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. He didn’t have much in the way of staff to work with, since the fledgling agency only had twenty-four law enforcement agents to cover the entire country. Ding worked closely with local law enforcement and sportsmen, however, and was surprisingly successful at curtailing poaching. In addition, Ding put in place several laws that are still on the books today, including making it illegal to bait waterfowl, use live decoys, and hunt with shotguns capable of holding more than three shells.

Ding was elected to membership in the prestigious Boone and Crockett Club, and after his retirement in 1935, he went on to become president of the National Wildlife Federation. Appropriately, he has a National Wildlife Refuge named after him—the J.N. Ding Darling NWR on Sanibel Island in southwest Florida, which is known for harboring exceptional populations of migratory waterfowl.