Take careful precautions to avoid run-ins with grizzlies if you’re hunting in their stomping grounds.

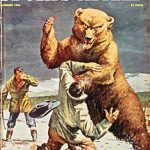

Photo above by Vic Schendel

Hunters are most likely to experience bear problems in three broad-category situations: while looking for game, while camping, and while handling, dressing, retrieving, or transporting downed animals. The primary rule when hunting in grizzly or polar bear country is to always be alert for bears, and/or to “stay bear aware.” That these maxims are practically clichés by now is unfortunate, because clichés tend to go right through people’s ears, or at most receive a gratuitous nod. “Stay bear aware, right, got it. Will do.” The advice is good, but a bit too pat and vague to be very helpful.

A biologist friend likes to be a little more specific. He tells Montana hunters, “Think grizzly, and think defensively. Assume that grizzlies are in the area, and that an encounter is very possible. Anticipate scenarios and how you will handle them. Have your self-defense deterrents within reach, and know how to use them in a hurry. Practice with gun and bear spray before you go hunting. Know the guidelines for handling different types of encounters.”

That’s an excellent start, but to really lower the odds of bear trouble in the key situations, we need to delve into more concrete details.

In grizzly country, for instance, “being alert for bears” means not only scanning for actual animals near and far, but also looking closely for evidence that bruins are in the vicinity. Bears tend to leave plenty of sign. Claw marks raked into tree bark; tufts of hair stuck in the bark of “rubbing trees” and fence wire; berry bushes bent, broken, and imperfectly stripped of fruit; logs torn apart (by grub-seeking bruins); digs where a bear has unearthed roots or ground squirrels; large, oval bedding depressions in grass or other vegetation; half-buried carcass caches; and of course scat and tracks. Several scat piles in one fairly small area can signal that you are near a bear’s bedding site.

Fresh tracks are important sign, of course, and it’s worth knowing how to distinguish a grizzly print from a black bear’s. Griz tracks are not necessarily larger, but the claws are usually longer than the toe marks, and the toe marks are jammed tightly together on a fairly straight line. Black bear toe marks are spaced apart and form a noticeable arc from large toe to small, with claw marks seldom longer than the toes. Remember, the idea here is to avoid bear trouble before it happens, so if you are encountering fresh grizzly sign or an abundance of sign, the smart move might be to change course or leave the area entirely and find another place to hunt.

Be especially alert and ready to defend yourself when hunting in the following high-risk conditions: In thick, heavy cover (where a large percentage of sudden grizzly charges occur); along noisy waterways, especially in tall cover; and on high-wind days. If you are hunting along and suddenly pick up the whiff or stench of a dead animal, don’t investigate. Back up and move well away to avoid the possibility of running into a carcass-defending griz, which could very well react with a defensive charge.

If you see a bear that hasn’t yet seen you, move out of sight quietly and leave the vicinity. If you see or meet a bear that sees you or approaches, stay calm, don’t call out or yell, don’t run or try to climb a tree, but do stand your ground and prepare your deterrent and/or weapon. If the bear doesn’t approach, slowly move back and away. Stop if the bear comes forward and stand your ground with weapons ready.

For hunters in grizzly country, one of the most potentially dangerous situations occurs after a game animal is down. This should be considered a prime-risk, red-alert time, and treated as such. (The risk is even higher if you are alone.) Have your bear spray at hand and your rifle or sidearm loaded, with a round chambered, and within easy reach. If possible, move the carcass away from thick brush and into the comparative open. If you are alone, stop, stand, and survey the surroundings every few minutes. Stay attuned to natural sounds around you, such as rustling brush, the crackle or crunch of leaves or twigs, alarm-chattering squirrels or scolding birds–any of which might signal an approaching predator. With partners, one person stands armed (with both spray and gun) and ready while the other does the field-dressing. If both people are needed to move or lift the carcass, at least one should keep surveying the surroundings during the effort, loaded weapon(s) within reach. When the gut pile is removed, it should be immediately placed on a piece of tarp or thick plastic drop-cloth and skidded as far as feasible (100 yards if possible) from the carcass. Bears will almost always go for a gut pile first. If you must leave the carcass, or part of it, for later retrieval, mark it with a stick and bright flagging tape. On the return trip, glass the flagged stick from a safe distance. If it has been disturbed, you know a bear might have found the meat. (Even better, attach a motion-detecting alarm device like a Critter Gitter to the carcass. The high-pitched alarm and flashing lights will ward off bears and other scavengers.) Whenever possible, pack rather than drag out game meat. Dragging leaves a scent trail bears can follow. Make plenty of noise while hauling out meat, to help alert and hopefully drive off any bears in the area.

Another prime time and location for bear trouble is while camping, and in a camp, “bear trouble” can mean more than personal safety. Anyone who has returned from a morning’s hunt to find tents, sleeping bags, packs, camp stove, lanterns, and miscellaneous other (expensive) gear torn, clawed, bitten, crushed, or carried off knows a thing or two about bear problems. I’ve also seen boats, rafts, and even a float plane wrecked or damaged by marauding bruins. (We’re talking about all three kinds of bears here: black, brown, and polar.) Camp-raiding night bears are another, more startling and serious, kind of problem, and the rare camp-invading predatory bear should be considered a possibility.

Start by positioning your camp wisely. Of course you want to be a good distance from any known bear trails or travel routes. Bears also use human trails, game trails, river and stream banks, and lake shores as travel and foraging lanes, so it’s best not to set up camp too closely to such thoroughfares. Whenever possible, choose a clearing for your tent site and avoid camping close to thick cover.

Everyone has heard the basic rule: “Keep a clean camp in bear country,” but not everyone realizes what a clean camp really means these days. First comes a sub-rule: Don’t sleep where you cook and eat. Ideally, the cook site should be about 100 yards from the sleeping tent, but this isn’t always realistic. Sometimes 100 feet or less is the best you can do, and that can suffice if the cleanup is scrupulous. Locate your cook site so that you can see an approaching bear while cooking or eating. (Try not to cook or eat near thick cover, or where your view of the surroundings is blocked.) Note the wind direction and remember that a bear is more likely to approach from downwind. Never leave food unattended (even if it’s sizzling in a pan). Despite being large, even cumbersome animals, bears have a way of suddenly appearing out of nowhere, especially when there are edibles to be had. Don’t try to burn or bury leftover food or garbage. What’s left behind in the fire ring or covered underground is enough to attract a bear. Ursid noses are unbelievably acute. They can smell sardines inside an unopened tin; they can pick up meat, fish, or bacon odors from as far as ten miles away, given the right atmospheric conditions. Bears have been known to break into a car and tear out the backseat to get at a food-laden ice chest locked in the trunk.

They also have a peculiar sense of what constitutes “food.” One hunter’s backpack was carried off and torn apart by a black bear because the pack contained a tube of toothpaste, which the bear ate down to the cap. Scented soaps, toiletries, and sunscreens can also attract bears. Inside a tent, crumbs from a candy bar or sandwich, a pack of chewing gum or mints, can be and have been enough to draw in a scent-following bruin. All such items, including canned goods, garbage, game scent, and clothing permeated with blood or food aromas, must be separated from the camp and either hung out of reach in bags or locked up in bear-proof storage containers. For secure tree-hanging, the bagged items should be suspended at least fifteen feet from the ground, and at least eight feet away from tree trunks. Locked bear canisters can be kept on the ground. But remember, although they are “bearproof,” they are not scent-proof. In other words, to a bear they still smell like food. So a bear can should never be kept inside or near a tent. Place it on level ground at least 100 feet away. A covering of clean pots and pans can serve as a bear alarm.

One way to make safe camping much easier, especially for hunters who have game meat or hides to protect, is to use portable electric fencing. Initially, the purist woodsman in me balked at the idea of such contraptions in the wild, but I’ve come to see the sense and value of an electric fence in certain situations. Some modern units weigh less than ten pounds, take about twenty minutes to set up, and have a very good track record at keeping out bears, including large grizzlies, even when game meat or a carcass is lying within the perimeter. (I do know of three cases where polar bears have broken through electric wire and attacked humans. True security while sleeping out in polar bear country usually involves rotational night-watches with armed guards, even when fences are used.) For an excellent review of how electric fencing works and the best ways to use it, check out biologist Tom Smith’s article, “Protecting Your Camp from Bears: Electric Fencing,” available on the Alaska Department of Fish and Game website: adfg.alaska.gov.