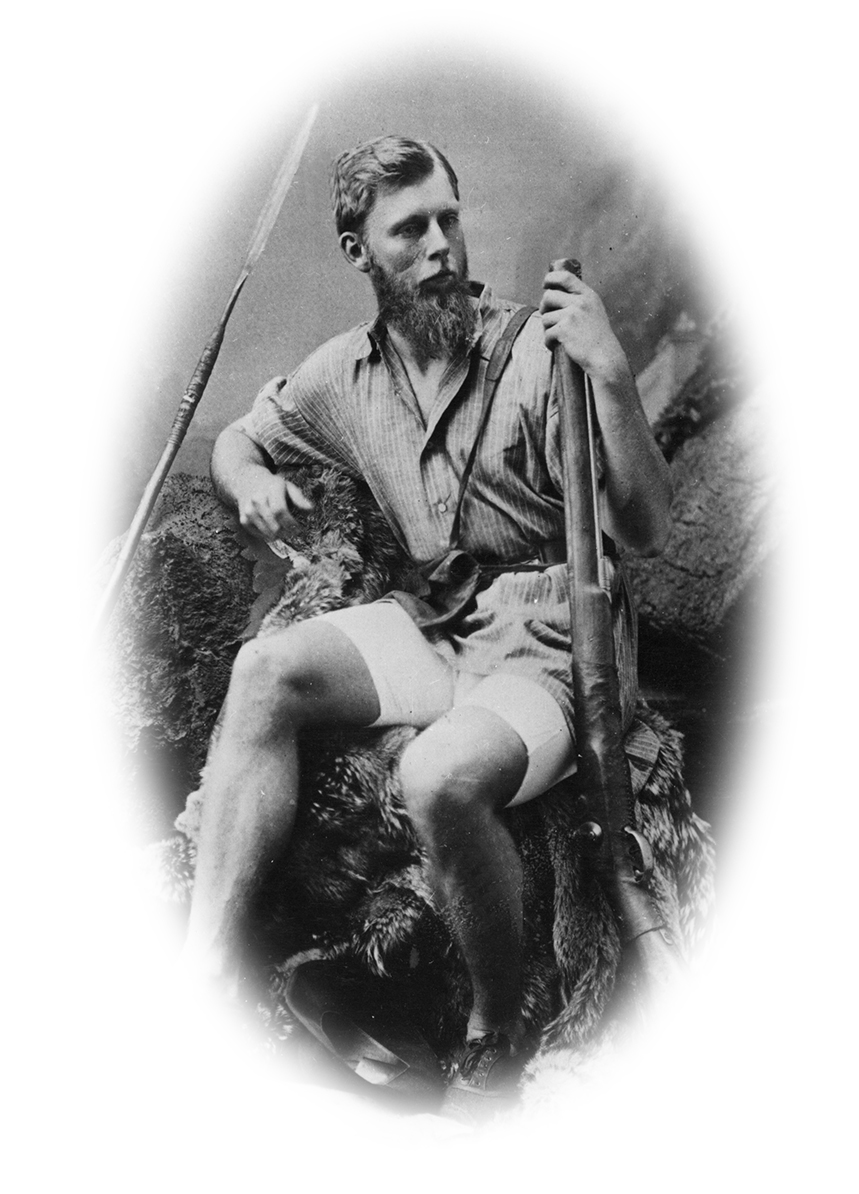

Before he became the most famous hunter of the Victorian Era, Frederick Selous nearly met his end when he ended up lost and alone in the wilderness of southern Africa.

He would eventually become one of the most famous and accomplished hunters of his time and a man of many distinctions, but in 1872 Frederick Courteney Selous was only nineteen years old and had just recently arrived in South Africa. It was his first visit to the continent he had read and dreamed about while growing up in England, and his first venture into the “far interior,” which was largely unmapped and roadless except for a few rutted wagon-track paths. Young Fred’s plan was to explore with three new-met friends, hunt as much as possible, and make money shooting and trading for ivory, which at that time was still considered a legitimate–and sometimes profitable–profession.

On horseback, with ox-drawn wagons full of trade goods and a retinue of native helpers, Selous and his cronies labored their way north from Port Elizabeth, a trek of some months with many delays and hardships. Around mid-August the men followed the wagon track into country ruled by the Matabele tribe although, except for a few scattered Bushmen, the area seemed largely uninhabited. At a place called Shakani, where there were two “pretty vleys” (shallow ephemeral lakes), they stayed for a week. Each day Selous rode out with one or more companions in search of game. He wrote, “we always guided ourselves back by a low range of hills that ran parallel with the [wagon track] road, behind the vleys, and particularly by one single hill that stood by itself.” In modern terms, they were using these hills as a baseline that could be followed to find their way back to camp, and the single rock-mound hill (or kopje) was a landmark that stood out in otherwise homogenous terrain.

Leaving Shakani, they continued northward, and after a four-hour trek reached Lemouni Pan, a large, open piece of ground surrounded by thick forest and scrubby brush. During the dry season it was almost destitute of water. August is mid-winter at that latitude, and though the sun was hot during the day–as hot as summer in England, Selous thought–the nights “were intensely cold, and tea left in the kettle was often frozen.”

Just before dawn one day, being completely out of meat, Selous and two companions decided to ride out on horseback in search of game. “So, hastily drinking a cup of hot coffee, we saddled up our horses and started.”

This would be his first serious mistake: taking off for the hunt with no thought of preparation and adequate equipment–not even a compass, or food and water, or a coat and blanket, or matches. After all, they were only going out for a half-day jaunt.

Early that morning they came upon some hartebeest, and wounding one, went on a long chase after it, finally losing the animal in thick woods. Thinking they were riding parallel to the main wagon track, they continued on until afternoon, seeing no game. About to give up and head back to the road, they spotted several giraffes in the distance, “their heads appearing amongst the tops of the trees. We at once started in eager pursuit, hoping to secure some steaks for supper, as giraffes are splendid eating … and their fat is a luxury that no one can properly appreciate till he has lived for a time on nothing but the dry meat of the smaller antelopes.”

Selous and his friends galloped toward the herd of about twenty animals, which took off with their gliding gait. “At a hard gallop, they can spin along for miles, and so we found today. After an hour or so [of chasing them on horseback at top speed] the giraffes separated and I found myself lying on my back, with my right leg nearly broken, by coming violently into contact with the trunk of a tree.” When Selous managed to rise, the giraffes were gone, and so were his companions.

Thinking they too must have given up the chase, he fired a signal shot and immediately heard an answering report to his right. He rode in that direction for some distance “and shouted with all my might,” but received no reply. He fired another shot, without effect. His horse was worn out from the hard chase, so he unsaddled for a time and attempted a third signal shot. He “listened intently for an answer, but all was silent as the grave; so, as the sun was now low, I saddled up again and struck a line for the wagon road, thinking my friends had already done the same thing.”

He kept riding, very slowly, on his spent, thirsty horse, as the sun sank on the horizon and finally disappeared. The moon was bright but the temperature was lowering fast. “Still thinking I must be close to the road, I kept on for a couple of hours or so, when, it being intensely cold, I resolved to try and light a fire and pass the night where I was. Having no matches, in endeavoring to get a light I had to make use of my cartridges, of which I had only three remaining.” He broke one of these open, rubbed some gunpowder into a piece of linen torn from his shirt, dropped it into the muzzle of his rifle and tried to ignite it with the percussion cap. He managed to get a bit of dry grass smoldering, but “could not for the life of me make it flare, and soon had the mortification of finding myself, after two more unsuccessful attempts, just as cold and hungry as before, and minus my three cartridges to boot. Were the same circumstances to occur again, no doubt everything would be different; but at the time I was quite a tyro in all forest lore.”

It was now very cold. His clothing consisted of a hat, shirt, trousers, and light shoes. Using his hat for a pillow, he pulled the saddle over his chest and hoped to “fall asleep and forget my cares; vain indeed, for the bitter cold crept in … from my feet upwards, til I was soon shivering from head to foot as if my very life depended upon it.” After two hours of this he could bear it no longer and struggled, stiffly, to get up. He ran back and forth in the moonlight until he was reasonably warm again, then lay down. In this manner he passed the long, frigid night.

At dawn he saddled up and rode, very slowly, on his poor horse, which was too fatigued and dehydrated to move faster. Coming near a high tree, he climbed it to look for a recognizable landmark. But “on every side the country was covered with forest, and in the distance were several low ranges of hills, yet nothing seemed familiar to my eye.” Spotting a lone kopje, he rode for it, passing “three beautiful gemsbuck, which allowed me to come quite close to them, though they are usually very wild; but they had nothing to fear from me, as I had no cartridges, and so could do nothing more than admire them.”

Then it struck him: he must have already ridden across the narrow wagon-track road last evening in the moonlight, when it would have been easy to miss. He became so sure of this he turned his horse around and rode back in the direction from which he’d just come. This is typical lost-person behavior, changing or reversing course on a sudden whim, filled with doubt and anxiety-based impatience, wanting to locate something recognizable, to once again feel safely re-oriented. Very often this leads people to change course just before they are about to reach the very place–the trail or turn or fork or road–they are seeking.

Selous kept on until midday, but there was still no road. “I began to think that I was in stern reality lost in the veldt, without even a bullet to obtain food for myself, and no water within heaven knew what distance away, except the far-apart drinking-places along the road. And where was that road–was it behind me or in front?”

Seeing another kopje, he climbed it for a look around. “A most bewildering prospect it was–a vast ocean of forest on all sides, as far as the eye could reach; but nowhere could I make out a landmark to guide me in the least.” He did see, in the direction from which he’d just come, a thin line of blue smoke curling up from the trees–which he took to indicate a wood fire made by a native who could probably guide him to safety. So he remounted his beleaguered horse, turned it around once again, and rode back in the direction of the smoke, now believing that the road had in fact been behind him. Recounting this later, Selous interjects, “I may here say that as I afterward found out, I never had crossed the road in the night, but must twice have turned and ridden away when within but a short distance [of it].”

Nearing where he thought the wood fire should be, he climbed a tall tree and searched, but could find no trace of smoke or human. Discouraged–and probably more worried and frightened than he admits in his narrative–he tried to keep his spirits up by imagining “how I should enjoy a cup of tea and a damper with my companions round the campfire.” (A frequent tactic of survivors is using pleasant imaginings and other goads to restore motivation while staving off panic and despair.) But “as the sun dipped lower and lower in the western sky, my spirits sank with it, and at last when it finally disappeared, I had to prepare for a second night on the bare ground, without food, water, fire, or blanket.”

Since his depleted horse had eaten nothing all day, he decided to hobble it with rawhide thongs rather than tie it to a tree, hoping the animal might forage during the night and gain some strength for the next day. “It was full moon, and fearfully cold, from which, in addition to hunger and thirst, I suffered intensely, almost shivering myself to pieces; but everything has an end in this world, and so had this most intolerably long winter’s night.”

At the first streak of dawn he tried to rise, but his legs were numb with cold. Eventually he restored enough circulation to stand, look around, and realize his horse was gone. Though tightly hobbled, the animal was so parched it must have hopped and shuffled off in search of water, despite the crippling restraints. Selous tried tracking it for a short while but the ground was so hard and dry he couldn’t find adequate spoor. Now he was lost and unequipped–and on foot. It had been forty-eight hours since any food or liquid passed his lips. But “all that day I walked as I have seldom walked since, only resting at long intervals for a few minutes at a time, devoured by a burning thirst and growing sensibly weaker from hunger.”

Near sunset he climbed a steep hill, pausing every few steps to pant and rest, only to reach the top and see “nothing but range upon range of rugged, stony hills.” Exhausted, he settled in for another frigid night. Now he was frightened, thinking he “was doomed to die of starvation and thirst in the wilderness, my fate remaining a mystery to all my friends.”

Instead of panicking, however, Selous’s thinking shifted, “a feeling that it was too hard to die thus like a rat in a hole, and though things certainly looked desperate at present, I still felt some gleam of hope that they would eventually come right.”

The cold was not so intense up on the mountain as it had been on the floor of the plain, “nor did I feel the pangs of hunger to any great degree; but my thirst was now intolerable, my throat, tongue, and lips being quite dry and swollen, so that it was very painful to swallow.”

When he awoke atop the hill he saw that he “commanded a view over a vast extent of country. Suddenly I fancied I recognized a certain detached kopje as the one with which I was well acquainted, close to [the] Shakani vleys.” He felt certain that if he could reach that kopje he would be saved, although it was very far away. He took off walking for it and marched all day, stopping periodically to climb a tree and relocate the landmark, which he couldn’t see from ground level. Though fatigued and weak, he wouldn’t rest for more than a few minutes at a time. At last, just before sundown, he was nearing the Shakani kopje when he saw two native men walking ahead. He called to them as much as his parched throat would allow. They led him to a small kraal consisting of three crude huts. He asked for water, but the old Bushman there would not give him any. “Holding a giraffe’s intestine full of the precious fluid under his arm, [he] said, ‘Buy the water!’” This infuriated Selous, but just then a boy came in carrying a large calabash of fresh goat’s milk. Selous offered his only tradable item, his clasp knife, which the boy accepted. The milk was an indescribable treat, and “about the very best thing I could have taken in my state.”

By the next afternoon he was back with his friends, eating heartily and very glad to be sleeping once again under warm blankets. “Thus terminated an adventure which, had it not been for a sound constitution, might have terminated me,” he wrote. He also noted that it was having the low range of hills and the kopje landmark “well impressed upon my mind” that had probably saved his life.

As for his horse, which he assumed had died of thirst or fallen prey to lions or hyenas, the hobbled animal had somehow managed to return to the native village where had Selous purchased it. Though in tough shape, its legs cut by the leather thongs, the horse–like young Fred Selous–had found a way to survive.

Author’s note: This account can be found in Selous’s A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa, (originally published in 1907, reprinted in 2019), an absorbing memoir of hunting, exploration, and natural history in southern Africa.