The “gray ghost” is widespread in Africa, but some regions are better than others.

With attractive gray hide, bright white vertical body stripes, and those magnificent spiraling horns, the greater kudu is among Africa’s most striking antelopes, and perhaps the most eagerly sought. Everybody who goes on safari wants a greater kudu!

First, you must seek them where they live. After the bushbuck, the greater kudu is the most widespread of the spiral-horned antelopes. Except for an isolated pocket where CAR, Chad, and Sudan meet, the greater kudu is primarily an animal of East and Southern Africa. It is found from Eritrea and Ethiopia down through Kenya, Tanzania, and Mozambique; then on west through Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Namibia, and down through much of South Africa. Even in parts of this region where the kudu is not native, it has been widely introduced.

There are many choices for a kudu safari. However, kudu densities vary widely. Although they need water, they do fine in arid country but, as browsers, they are primarily creatures of thornbush and woodland. They love hilly country, are rarely found in open grasslands, and never in swamps.

The several races of greater kudu are visually identical, but there are size differences. Rowland Ward recognizes four regional groupings: Western, Abyssinian, East African, and Southern greater kudu. SCI echoes these, but adds Eastern Cape greater kudu because the kudus of South Africa’s Eastern Cape region are shorter in horn, and this population is geographically isolated.

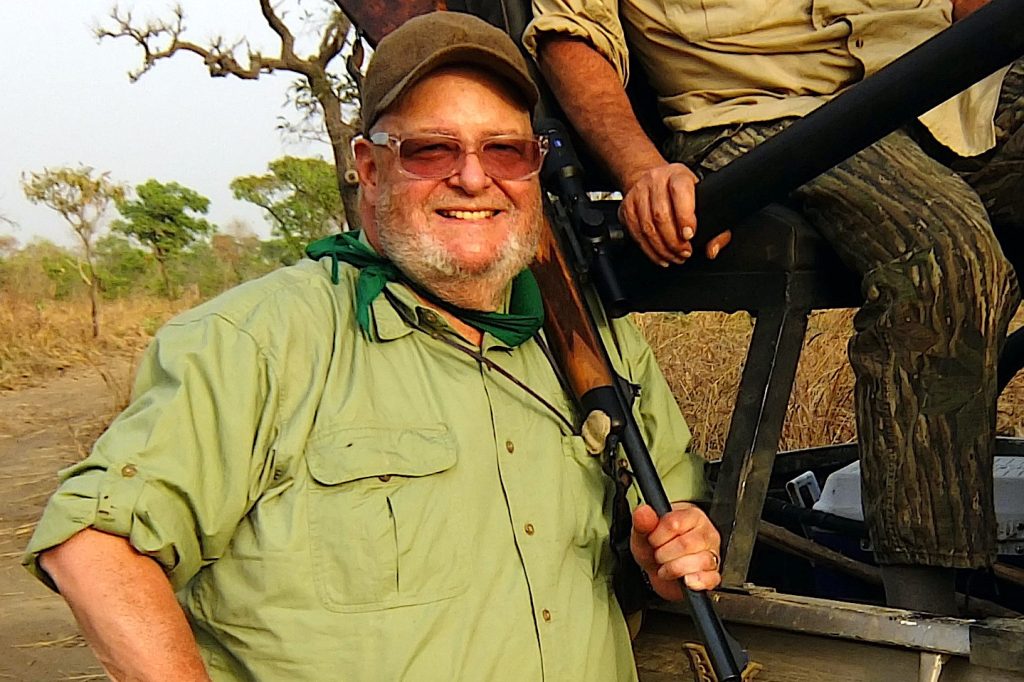

The Western greater kudu, also isolated, is the smallest. I hunted this kudu in southeastern Chad. I saw my bull silhouetted on a skyline and he looked like a giant. When I walked up to him, I wondered where the rest of the animal had gone! He was a third smaller than all other kudus.

The Southern greater kudu grows the largest horns. RW’s Top 10 Southern greater kudus are alllarger than the current world record for any other greater kudu! Most African hunters desire a kudu and, of course, everybody wants a big kudu. If you peruse RW’s listings, you will instantly note that seven of the Top 10 southern greater kudus were taken in South Africa. More on this in a moment.

Kudu populations have changed, and African hunting has changed. In his landmark work Big Game Shooting in Africa (1932), Major H.C. Maydon wrote that Eritrea was “the best kudu grounds” in Africa. Maydon took an awesome 55-incher in 1927. Obviously, he found kudus plentiful then, but no longer. Greater kudus are on license in Ethiopia, but populations are scattered and thin on the ground. Today, an Abyssinian greater kudu is harder to come by than a mountain nyala.

When we read older accounts, we get the idea that kudu hunting is difficult and chancy, the kudu often described as the “gray ghost.” On his 1933 safari in Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Ernest Hemingway struggled for a greater kudu, and finally prevailed. Twenty years later, also in Tanganyika, Robert Ruark struggled harder, and never got his kudu. Most safaris before 1970 took place in East Africa. Both Kenya and Tanzania produced some fine heads, but the greater kudu was never a common antelope in either country.

In 1988, hunting with Michel Mantheakis in Tanzania’s Masailand, I shot a beautiful 52-inch kudu; the way the trackers carried on, you’d have thought it was a hundred-pound tusker! Twenty years later, also with Mantheakis on Tanzania’s southern border, we saw lots of greater kudus, and I took one of my best. There are kudu hotspots in East Africa. However, the primary reason the old accounts make kudu hunting seem so difficult is that they were hunting them in the wrong parts of Africa.

The Southern greater kudu is far the most numerous and, in much of Southern Africa it is the most common large antelope. It’s still the gray ghost, never easy to hunt, but your chances are better if you hunt where there are lots of them!

So, let’s take a little tour around Southern Africa. The current world record, an astonishing bull, 73 inches around the curl, was picked up in Mozambique by Dr. Carlo Caldesi. Must be a great place for kudu, right? Yes…but not everywhere. Most of my Mozambique hunting has been near the mouth of the Zambezi. Kudus are on license, but the area is too wet; I’ve never seen a kudu there. Farther inland, on the Kruger boundary, around Gorongosa National Park, up the Zambezi, and north around the Nyasa Reserve, kudus are fairly plentiful and quality is good. A kudu is a normal part of a safari bag for hunters willing to put in the time.

Pretty much the same applies to Zambia, although I’ve never taken a kudu there. My sense is that kudus, though widespread in Zambia, are rarely plentiful, but quality is good. In 1996 in the Kafue, campmate Gary Williams took a monster 58-incher, one of the biggest kudu bulls I’ve ever seen on the ground. In July 2021, in Luangwa North, son-in-law Brad Jannenga got a nice bull without extreme effort. We saw quite a few kudus, including a bigger bull that gave us the slip. Although I’ve done six safaris in Zambia, I’ve never invested time in hunting kudu because, like most people who hunt that country, other game was a higher priority. Make kudu a priority, put in the time, and Zambia should produce.

Botswana is a sleeper destination for kudu, with ideal habitat except in the depths of the Kalahari. In the 1980s, when elephant hunting was closed, Botswana competed with Zimbabwe in the “buffalo-and-plains game” market. A nice kudu was routinely part of the bag.

In the Okavango in 1985, PH Ronnie MacFarlane announced one morning: “We’re going to go to a river I know of and get your kudu.” We arrived at midday and the area was teeming with kudus. I think I saw fifty bulls!

Today, with hunting in Botswana reopened, overpopulated elephants are the biggest draw, but don’t overlook the excellent plains game hunting, especially on some of the huge private ranches.

Zimbabwe is a small country, but awesome for kudu. I shot my first kudu there in 1979, in the southeastern Lowveld with Barrie Duckworth. Zimbabwe also showed me the biggest kudu I have ever seen. Brittany and I were hunting buffalo with Andrew Dawson along the Chewore River in the Zambezi Valley. This monster was casually browsing along the far bank. He was over the magical 60-inch mark, just a question of by how much. But neither of us had a kudu on our licenses!

The Zambezi Valley produces big kudu bulls, but that’s not where I would look because all antelopes are fairly thin on the ground. Instead, I’d consider the Matetsi blocks, or the big conservancies in the south, where densities are higher. Mugabe’s land grab ruined a lot of carefully nurtured habitat, but much remains, and a good kudu is probably Zimbabwe’s top specialty.

In Namibia, the Southern greater kudu is the most widespread large antelope. Most of Namibia is arid, but densities are probably highest in central Namibia and the north, which is better-watered and with the dense thornbush that kudus love. With limited dangerous game, Namibia is primarily a plains game destination, with a good kudu routinely a part of the bag.

Unfortunately, Namibia has been periodically hit by a disease that especially impacts kudu and eland. Often called “rabies,” scientifically it may not be, but kudu populations in some areas have been seriously reduced. The kudu is one of the slowest-maturing antelopes, requiring twelve years for maximum horn growth. Recovery takes time and, in some areas, numbers and selection are not what they might have been a few years back.

As with any pandemic, some areas have been hit harder than others. Namibia has plenty of kudus, and good bulls. On a ten-day plains game safari, I still expect hunters to take a good kudu, but in some areas they might have to hunt harder.

Let’s return to South Africa, which dominates RW’s Top 10…and accounts for a shocking thirty-one of the Top 50 RW Southern greater kudus. This suggests South Africa must be the best place, especially if you’re looking for an exceptional bull. Maybe. South Africa has the genetics. And the country has not had the same problems as its neighbors: no disease like Namibia; no long civil war like Mozambique; no land grab like Zimbabwe.

There is a fly in the ointment, caused by the great game-ranching industry that, in my lifetime, took South Africa’s wildlife from rags to riches, and made the country Africa’s top safari destination. Prices for big kudu bulls have skyrocketed, not only among hunters, but for breeding stock. When discovered, big kudu bulls are often captured and taken to auction. This happens mostly in the north, where the biggest kudus live, and where game ranching is most intensive. This does not apply to all areas and operators, but it’s widespread enough to be a concern.

Northern South Africa remains excellent for big kudu bulls—at higher prices—but don’t overlook the Eastern Cape. You are unlikely to get a 54-inch kudu there—these kudus are smaller—but kudu densities are high, and trophy fees are lower. If I wanted a good chance at a nice kudu bull, I’d think about Eastern Cape. Now, if I wanted a really big kudu bull, then I’d do serious research, and I’d plan on hunting hard.