Photos by Tweed Media International

Steep green hills and sturdy garron ponies are the backdrop to a magnificent red stag hunt in the Scottish Highlands.

The two ponies, tied nose-to-tail, were small and sturdy, with shaggy manes and placid demeanors. Our tweed-clad ponyman, recognizing my interest in all things equine, let me hold the halter rope and pet the lead pony’s nose beneath the long forelock. I noticed its packsaddle, a different type from any I had ever seen.

“Aye, some of these saddles are more than a hundred years old. They dinna make many of them anymore,” Alistair, head stalker at Drummond Estates in Perthshire, Scotland, had told me earlier.

A hunt for red stags in the Scottish Highlands is steeped in tradition, most of which has changed very little in more than a century. Your guides—called stalkers—still wear tweed from head to toe, although they’ll pull on a high-tech rain jacket when necessary. Each guide has his own “beat,” or section of the estate, which he knows like the back of his hand. You’ll cover ground—lots of it—on foot. And you’ll limit your shot to 200 yards, belly-crawling through the long grass and using dips and folds in the terrain for cover on the windy, treeless hillsides as you try to get within range of a mature stag.

One of the few things that haschanged in the Highlands in the last century is the method of game recovery. Traditionally, game was taken off the hill on the back of a sturdy Highland pony, also called a garron. These days, most of the places you’ll hunt in Scotland use more expedient—and lower-maintenance–Argos to transport game (the slopes of the Highlands are far too close to vertical to allow the use of ATVs or other wheeled vehicles). But a few estates, Drummond among them, still take stags off the hill the old-fashioned way—lashed to a hundred-year-old saddle on the back of a pony originally bred for this specialized task. The ponyman, typically leading a pair of garrons (one to carry the stag and one to keep the other pony company), follows the stalkers all day, at some distance, with his charges.

“What a cool job you have,” I said to Jack, our ponyman.

“Aye,” he grinned. “I canna believe someone pays me to do this!”

A moment of bonding with a Highland pony.

So far on this hunt, I hadn’t given the ponies much work to do, other than haul our lunches and a Thermos of hot tea to the rugged summit of a ridge. I wasn’t sure if this height was high enough to be classified a “munro”—a peak over 3,200 feet—but our two-hour hike up that morning sure had felt long and steep enough to classify. Now we were taking a break at the top, huddled behind a jumble of rocks in an attempt to escape the incessant, gusting wind. It had been spitting rain on the way up, and we were socked in with fog here at the top. It was exactly as I had imagined Scottish weather would be.

This gray, frigid perch was a full one-eighty from the luxurious accommodations I had left that morning. I was staying at the world-famous Gleneagles Resort, built in the 1920s to host the well-heeled for a traditional Scottish country holiday of golf, shooting, stalking, and fishing. In recent years it has hosted the Ryder Cup and even a G7 summit, but Gleneagles remains true to its roots and still offers stag-stalking excursions on nearby estates, including this one. The hotel provides a driver to whisk you off to your adventure and pick you up at the end of the day, as well as sending along a magnificent lunch of roast beef sandwiches and Scottish eggs, which I was now wolfing down and following with gulps of hot tea. The combination was finally beginning to counteract the damp Highland chill.

The fog was beginning to lift, too, just as our stalker, Paul, had hoped it would. As the sky cleared, we got to our feet to continue the hunt and I was treated to a big reveal, the reward for the steep climb that morning—a stunning panorama of grassy hills, rocky cliffs, and a marshy green valley far below.

The wind, however, refused to abate. It swirled around us maddeningly as we moved along the ridgeline, glassing the slopes below for deer. Stalking in the wide-open Highlands is all about using the terrain, so you’re always hiking up and down, going around knobs and points and finger ridges. The deer, including a few huge herds of forty or fifty animals, were mostly tucked into the hillside directly below us to escape the wind, and despite our best efforts on every stalk the tricky winds swept our scent to the deer almost every time.

By late afternoon we had come to a hilltop crowned with enormous peat “hags,” which look like giant, grass-capped mushrooms of soft peat moss. These provided excellent cover for stalking a herd with several mature stags, but the deer were restless and spooky. We ran from vantage point to vantage point, crawling on hands and knees to peer around the hags, until my pant legs and gaiters were smeared brown with peat mud. When a chance finally came and I settled belly-down behind the rifle, all the deer were facing us, and then, as one, the herd turned and headed directly away at a trot, providing no shot opportunity. And that was the end of my first day of stag stalking. A GPS phone app showed we had hiked eighteen miles.

Fortunately, there was more to come. After a magnificent meal at Gleneagles’ high-end Strathern restaurant that evening—naturally, I ordered wild Highlands stag in a red wine sauce—and a good night’s sleep in the luxurious bed, I was back at the estate the next morning as the stalkers gathered their gear and saddled up the ponies. Although it was still windy, it was a bluebird day, with clear skies and plenty of sunshine.

This morning my guide was Alistair, the estate’s head stalker. The head stalker is awarded the estate’s best “beat,” so I felt pretty confident as we headed out. We trekked upward along the edge of a small clearcut, topping the ridge in about an hour and a half, and began to glass the surrounding hillsides. I could see our ponyman, Jack, shadowing us with his two charges, just specks on the slopes far below.

The blue sky set off the green hillsides, covered with lush tall grass. The scenery got even prettier when we started spotting deer. There were several large herds of hinds and young stags feeding along the lower slopes, and we covered plenty of ground just as we had done the day before, working our way along the heights and studying the herds through our binoculars.

In the early afternoon we spotted a large herd—some forty or fifty deer—with several mature stags. Alistair and I were able to belly-crawl to the edge of the slope and I rested the rifle, a borrowed Sauer 404 in 6.5 Creedmoor, on my daypack, studying the restless herd below. The stags on the near edge of the herd were just within our 200-yard limit, but they were milling restlessly, and the stag I wanted never stepped clear. We watched them for fifteen minutes or so before the entire herd began to move away from us; soon they were five or six hundred yards distant.

We wormed our way back from the edge and then then jogged around the back of the hill and up the next couple of rises until the herd came back into view. It looked as though they had finally relaxed, with about half the deer bedded down in the tall grass. We were well inside our range window this time, so I got comfortable in a prone position behind the scope once again. Alistair explained which stag he wanted me to shoot, but it was bedded, facing away from us. I wasn’t worried; I’d wait for the right opportunity and be ready when the stag stood. It was comfortable lying there on the soft hillside, bathed in warm sunlight with the cool breeze washing over us.

Twenty minutes later, as if responding to some prearranged signal, the entire herd, including my stag, stood up and moved off, straight away from us, and vanished over a rise. Once again, I never had a shot.

Though frustrated, I had to admit I was impressed. The wide-open country and the large numbers of deer had caused me to assume that stag stalking in Scotland wouldn’t be particularly difficult. I was quickly learning how wrong I had been.

I was afraid we had blown our last chance; the afternoon was wearing on, and the big herd had seemingly vanished. We went around the crest in the direction the herd had gone and dropped down again off several fingers, searching in vain. How could several dozen coppery-red deer simply vanish on a wide-open, green hillside?

Alistair, however, was not one to give up, no matter the odds. Since the deer were not above us or on our level, there was only one place they could be—far down below us, tucked in somewhere on the lower slopes. To my amusement, he sat down and began sliding down the steep slope on his butt, so I followed suit. It was easy and fun, riding the soft, slippery grass down the hill like kids on a slide. We slid a couple of hundred yards, with Alistair stopping occasionally to peer directly below us with his binocular. Then we’d resume our slide. Finally he stopped, flipped onto his belly, and crawled to a slight lip in the hill. He looked back at me and motioned me to join him. I slithered up beside him like a snake.

When I peered over the lip, I was astonished to see the deer, looking surprisingly relaxed, some 180 yards straight down below us. The rifle was resting once again on my daypack, and I studied the herd through the scope as Alistair talked me skillfully onto the right stag—not an easy task in such a large group of deer. At first, other stags were standing too close or behind him, but eventually he stood clear. My opportunity had come at last.

The trigger on the Sauer 404 had been adjusted to require only a light touch, and I squeezed gently as soon as I was steady on the stag’s chest. The entire herd bolted, but my stag lagged behind, staggered, and fell.

I took my eye off my fallen stag only when I realized the rest of the herd was passing right by us at fifty yards, unaware of our presence, making their way back up the hill in a stately procession: hinds, young deer, and stags of every size. It was a magnificent sight.

Alistair bounded joyously ahead of me down the near-vertical slope, while I picked my way carefully to where my stag lay. Long winters and low forage make life tougher for stags in the Scottish Highlands than it is in some other parts of the world where red deer occur, but my stag was in beautiful condition, with a sleek copper coat and fine, tall antlers with good mass and four points on each side. A strip or two of velvet still hung from the lower tines.

Diana Rupp admires a fine Highland stag taken on the second afternoon of the hunt.

Alistair handled the gutting—which the Scots call the gralloch—and at last it was time for the Highland ponies to get to work. Paul had come up to help, and I held the halter while he, Alistair, and Jack heaved the stag up onto the pony’s back and tied it skillfully to the saddle hooks. They then lashed the stag’s head along its back so the antlers would not gouge the pony’s flank. Through it all, the garron stood placidly, a veteran of this task, and its companion watched, switching its tail as if knowing that it was getting off easy this time.

Jack led the ponies down toward the valley in the orange glow of late afternoon. Cooling temperatures and a yellow tinge to the grass signaled that despite the calendar reading late August, fall had already come to the Scottish Highlands. But the real proof was in the century-old scene on the slope below me: three hunters in traditional tweed with two sturdy ponies, one bearing a fine Highland stag, all of us heading home from the hill.

Gleneagles Resort

Gleneagles Resort

Since opening its doors in June 1924, Gleneagles has been one of Scotland’s most iconic hotels and sporting estates. Set beneath the Ochil Hills, in the heart of Perthshire, the 850-acre estate epitomizes Scotland’s natural beauty. In addition to 232 sumptuous bedrooms and suites, the hotel boasts nine restaurants and bars, including Andrew Fairlie, Scotland’s only two-Michelin-starred restaurant, and the opulent American Bar, featuring cocktails inspired by the Roaring 20s. There are three championship golf courses, an award-winning spa, and a sporting clays facility with instruction available.

Gleneagles now also offers deerstalking, the most traditional of the Scottish country pursuits. Hunters spend a day in the magnificent hills accompanied by a stalker who knows the ground intimately and will show guests how stealth, field skills, and an understanding of the wild deer can take them within range of these majestic beasts. Guests are provided with a delicious picnic, as well as clothing, optics, rifles, and ammunition, as well as transport to and from the hotel.

Price is £1,095 ($1,400) per person per day for stag, £750 ($980) per person per day for roe deer or red hind. Rooms at Gleneagles start at £520 ($680) per night based on double occupancy, and include a full Scottish breakfast each morning and use of The Health Club facilities. For more information, visit www.gleneagles.com.

Gear For Stag Hunting

A Sauer 404 rifle in 6.5 Creedmoor, topped with a Leica scope and loaded with Hornady’s 143-grain ELD-X Precision Hunter ammunition, was the ideal tool for a Scotland stag hunt. Suppressors are standard equipment when hunting in this part of the world and my rifle was equipped with one.

Leica’s Geovid Range 10×42 is an excellent binocular, and its rangefinding capabilities are impressive. I had no trouble ranging stags several hundred yards away despite frequent mist and fog, and the LED readout was bright and sharp, as was the optical quality.

I wouldn’t have handled the damp, windy conditions of the Scottish Highlands nearly as well without my Swazi Shikari Coat, which is 100 percent waterproof and windproof and an ideal layer for any hunt in similar conditions. Swazi gaiters were also invaluable; without them my pant legs would have quickly soaked through after hiking through the tall, wet grass.—D.R.

Leave a Comment

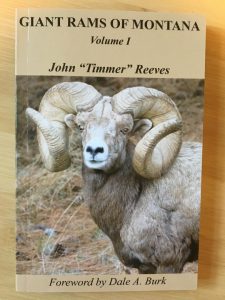

nyone who is fascinated by bighorn sheep, and especially big rams, will be intrigued by this fascinating new book by Butte, Montana, author John “Timmer” Reeves. Giant Rams of Montana, Vol. 1, is a 272-page softcover book containing a collection of stories and full-color photos of the largest bighorns ever taken in Montana.

nyone who is fascinated by bighorn sheep, and especially big rams, will be intrigued by this fascinating new book by Butte, Montana, author John “Timmer” Reeves. Giant Rams of Montana, Vol. 1, is a 272-page softcover book containing a collection of stories and full-color photos of the largest bighorns ever taken in Montana.

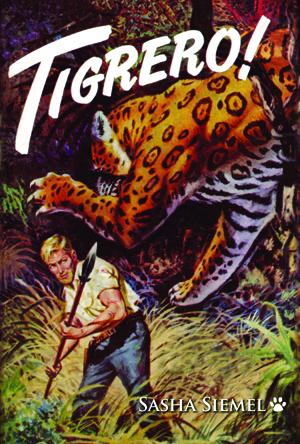

One of the most interesting hunters of the twentieth century has been nearly forgotten today, but Sasha Siemel’s exploits live on in his excellent book, Tigrero! His hunts for the fierce jaguars in the jungles of Brazil—armed only with a spear—will leave you breathless. He guided many notables, including Theodore Roosevelt Jr., on expeditions and hunting adventures in the South American jungles. Siemel was so famous in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s that he appeared in liquor advertisements, Hollywood films, and even in a full-length feature article in the New York Times. His autobiography was published in 1953, and this new edition has been revised and expanded to include new stories by Siemel and a large selection of photos and illustrations.

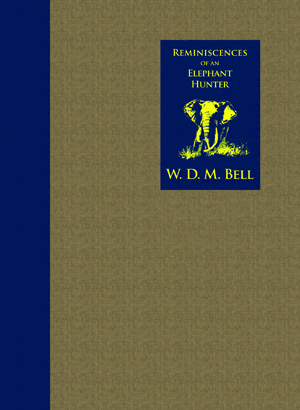

One of the most interesting hunters of the twentieth century has been nearly forgotten today, but Sasha Siemel’s exploits live on in his excellent book, Tigrero! His hunts for the fierce jaguars in the jungles of Brazil—armed only with a spear—will leave you breathless. He guided many notables, including Theodore Roosevelt Jr., on expeditions and hunting adventures in the South American jungles. Siemel was so famous in the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s that he appeared in liquor advertisements, Hollywood films, and even in a full-length feature article in the New York Times. His autobiography was published in 1953, and this new edition has been revised and expanded to include new stories by Siemel and a large selection of photos and illustrations. Readers who have enjoyed Walter “Karamojo” Bell’s other books—especially his classics Karamojo Safari and The Wanderings of an Elephant Hunter—will not want to miss two brand-new volumes of this great hunter’s writings. Compiled over the last several years from long-lost manuscripts left by Bell upon his death, both books have all the adventure, description, and riveting writing style Bell is known for. Incidents from an Elephant Hunter’s Diary is a collection of his never-before-published short stories, exploring Karamoja, Uganda, and the French Congo. Reminiscences of an Elephant Hunter is the complete autobiography of Bell, recounting his full life story, as well as more great adventure stories he wrote over the years, and an interesting section of letters and records from Bell’s varied and adventurous life. It’s a treasure trove for anyone interested in this exceptionally fascinating man.

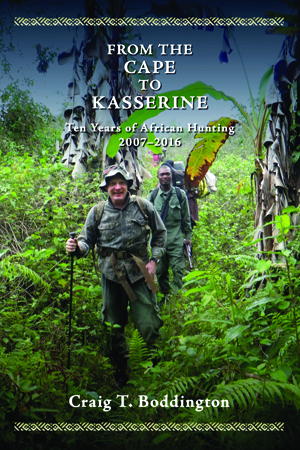

Readers who have enjoyed Walter “Karamojo” Bell’s other books—especially his classics Karamojo Safari and The Wanderings of an Elephant Hunter—will not want to miss two brand-new volumes of this great hunter’s writings. Compiled over the last several years from long-lost manuscripts left by Bell upon his death, both books have all the adventure, description, and riveting writing style Bell is known for. Incidents from an Elephant Hunter’s Diary is a collection of his never-before-published short stories, exploring Karamoja, Uganda, and the French Congo. Reminiscences of an Elephant Hunter is the complete autobiography of Bell, recounting his full life story, as well as more great adventure stories he wrote over the years, and an interesting section of letters and records from Bell’s varied and adventurous life. It’s a treasure trove for anyone interested in this exceptionally fascinating man. Arguably the most famous hunting writer alive today, Craig Boddington has penned numerous books that are always interesting and entertaining reads, full of know-how and advice gleaned from his unparalleled hunting and shooting experience. Craig has now been hunting in Africa for more than forty years, and every ten years he has written a book chronicling the most recent decade of his adventures. His latest is From the Cape to Kasserine, detailing his hunts from 2007 to 2016, and it does not disappoint. From driven wild boar in Tunisia to elephants in Botswana, buffalo in Mozambique, lions in Tanzania, and offbeat trips to Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Liberia, he explores both popular and little-known hunting destinations and takes us along for a most enjoyable ride.

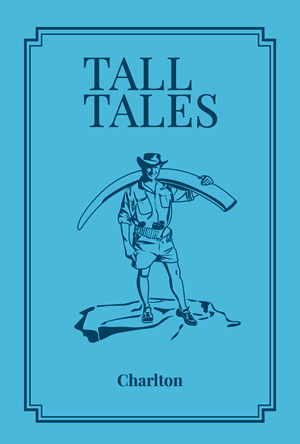

Arguably the most famous hunting writer alive today, Craig Boddington has penned numerous books that are always interesting and entertaining reads, full of know-how and advice gleaned from his unparalleled hunting and shooting experience. Craig has now been hunting in Africa for more than forty years, and every ten years he has written a book chronicling the most recent decade of his adventures. His latest is From the Cape to Kasserine, detailing his hunts from 2007 to 2016, and it does not disappoint. From driven wild boar in Tunisia to elephants in Botswana, buffalo in Mozambique, lions in Tanzania, and offbeat trips to Ghana, Burkina Faso, and Liberia, he explores both popular and little-known hunting destinations and takes us along for a most enjoyable ride. If you’ve ever watched professional hunter Buzz Charlton’s hair-raising elephant-hunting DVDs, you know this Zimbabwe PH is a fearless and personable character. In his new book, Tall Tales: The Life of a Professional Hunter in the Zambezi Valley, Charlton tells stories of his twenty-five years guiding safari hunters in the field. His stories range from his learning days as an apprentice PH—some of the funniest tales in the book—to adventures with clients of every imaginable stripe. Known for tackling crop-raiding elephants and ornery tuskless cows in the thick jesse of the Zambezi Valley, Charlton has had plenty of adventures, and he recounts them well.

If you’ve ever watched professional hunter Buzz Charlton’s hair-raising elephant-hunting DVDs, you know this Zimbabwe PH is a fearless and personable character. In his new book, Tall Tales: The Life of a Professional Hunter in the Zambezi Valley, Charlton tells stories of his twenty-five years guiding safari hunters in the field. His stories range from his learning days as an apprentice PH—some of the funniest tales in the book—to adventures with clients of every imaginable stripe. Known for tackling crop-raiding elephants and ornery tuskless cows in the thick jesse of the Zambezi Valley, Charlton has had plenty of adventures, and he recounts them well.

Gleneagles Resort

Gleneagles Resort