Traveling with firearms is usually not a problem… until it is.

Traveling with sporting firearms isn’t getting any easier. On the one hand, this is understandable; ours is a strange world these days, and people are nervous. On the other hand, although some airlines and airports have unique rules, the basics haven’t changed. Follow the rules, have the paperwork, allow plenty of time, and you shouldn’t have trouble.

Within the United States the basics are the same: Your firearms must be unloaded, and, if possible, disassembled. These days, we add trigger locks. Firearms and ammunition should be separated, and firearms should be in a secure hard case with all the lock holes filled with locks. Ammunition may be in checked bags, no more than five kilograms (eleven pounds). In Europe and within South Africa, a separate ammo case must be locked and checked separately.

Airline rules can change, however, and not all carriers allow firearms. Check the websites carefully or use a gun-savvy travel agent. Within the U.S., New York City’s airports are problematic: When checking in and out, the Port Authority must inspect firearms. Theoretically transit is OK, but recently there have been checked gun cases pulled for inspection. If possible, it’s best to simply avoid JFK or La Guardia if you are traveling with firearms. If it’s unavoidable, have your ducks in a row and allow plenty of time.

There really isn’t much paperwork required, but you better have it and know the rules. In Italy we had our consular permits, easily obtained.

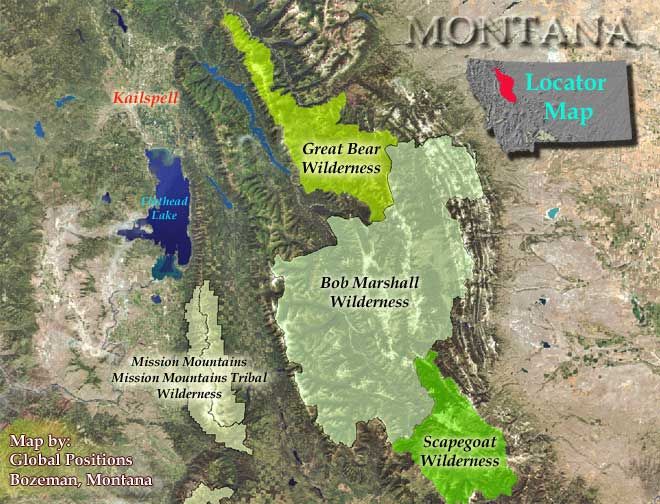

International destinations vary. Some airlines refuse to transit firearms through the U.K. Again, it’s theoretically possible, but best to avoid. Always consider the “what-ifs,” such as delayed or cancelled flights. Gun-friendly connections in Europe include Amsterdam, Frankfurt, and Paris; in Asia, Dubai and Istanbul. Some of these airports require advance police clearance. I’ve done this in Amsterdam and Dubai; their systems work, but this is another step that takes planning and time.

Ticket agents have every right to determine whether you will be allowed to transit and will be allowed entry at your final destination. So, where possible (and for sure where required) insist on having your permits e-mailed to you before departure. Print them and have them ready. In many key destinations, including Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, you get your gun permit on arrival—but you can print and fill out the form before you go and have it ready. If you run into a problem, keep your cool. Take as many deep breaths as necessary to stay polite, and ask for a supervisor. Above all, ensure you allow plenty of time to check in and plenty of time for connections. Two hours is minimal, and three is much safer.

Little of this is new, but it’s good advice, so I’m still wondering why I didn’t take it on my last trip! The more complex your itinerary, the more chances for error, which is how I nearly got into trouble this last go-around. Donna and I had planned two back-to-back hunts in Europe, first a roebuck hunt in Italy for both of us, then an ibex hunt in Spain, with only Donna hunting. After Spain she was going home and I was going on to Mozambique. All three outfitters have good rifles available, but we opted to take our own. In Mozambique the actual permit is issued on arrival, but your outfitter needs the details in advance. Italy and Spain have similar rules: Their consulates gather info (invitation letters, firearms specifics, passport photo, current U.S. hunting license, etc.) and issue authorization.

Although foreigners hunting in Italy is new, their Consulate was responsive and efficient; we had Italian temporary permits in less than a week. Spain has the largest outfitting industry in Europe, so the process should be routine, but our nearest Spanish Consulate (in Los Angeles) ignored both phone calls and e-mails until it was too late. Our Spanish outfitter, Pablo Carol, told us such things have happened before. The police might issue permits on arrival; the worst case scenario was they would keep our firearms locked up until we departed. Note: I do not recommend traveling with firearms without full clearance, but at this point we were stuck, so took our chances.

The Italian authorities at the Rome airport were wonderful; in five minutes we were on our way with sincere wishes for good hunting. Spain’s Guardia Civil was also wonderful. We brought all the paperwork for the consular permits, and they almost issued them, but it was late and an officer with enough rank wasn’t present. We could come back the next day, or they would keep our firearms until departure. Rather than lose a full day of hunting, we chose the latter option and Donna shot her ibex with a borrowed rifle.

In Spain Donna obviously did fine with a borrowed rifle, in this case a very heavy .338 Lapua. Donna isn’t very tall; borrowed rifles are usually too long in the stock, so she always prefers to bring a rifle that fits…but sometimes there’s no choice.

Back at the Madrid airport, we collected our gun cases and ammo with no problems. Donna made her midday flight to the States, and I had an evening flight on Iberian Airlines to Johannesburg connecting onward to Beira on South African Airways. And that’s where the real trouble started.

Iberian Airlines refused to check my bags onward to Beira. In part it was a travel agent error, with the Iberian and SAA tickets not properly linked. But it was more than that, in that Iberian maintained they had no baggage forwarding agreement with SAA—even though I had it in the fine print on my itinerary. They further maintained that firearms could not be transferred, only checked point-to-point. This is not true, but no amount of discussion would sway them. Rather than keep trying and wind up getting arrested, I took my deep breaths and accepted my fate: I was going to South Africa, even though that was not my final destination.

Here’s where complacency compounded the error. I’ve gone “in transit” through Johannesburg’s O.R. Tambo airport many times. I know the drill and how long it takes, so I had allowed a tight connection of just 90 minutes, much shorter than I recommend. It should have been fine, but now I had to enter South Africa, collect my bags, get a temporary South African permit, recheck at SAA, and exit South Africa. There was virtually no chance I’d make my flight to Beira. I did have all necessary phone numbers. I called my Mozambique outfitter, Mark Haldane, and told him I was likely to miss the Beira flight and thus the charter from Beira to camp. Turns out he had been in Johannesburg and would also be on the Beira flight. I called travel agent Barb Wollbrink several times. She was unable to fix the Iberian problem, but she called Henry Durrheim of Rifle Permits in Johannesburg. The South African gun permit process is simple and I often do it myself, but with time so critical, I’d have a better chance with a permit service.

Recognizing the upcoming hassles and unnecessary costs, this was probably the most stressful flight I’ve ever made, but we left Madrid precisely on time. With long flights this often means an early arrival; we landed a half-hour early, so now there was a chance! I was quick off the plane, but the immigration line was long. My duffel was on the carousel when I got there; I threw it on the trolley and trotted for the exit. One of Henry’s folks was waiting, so we dashed to the police office, where my rifle and ammo cases were waiting. October is past peak safari season and nobody else needed a permit. I filled out the form, secured the permit, and we headed for the SAA desks.

Haldane was at the gate and we were exchanging progress reports—the Beira flight was delayed ten minutes. This just might work!

At SAA I got much-needed help: The young ticket agent told me that she didn’t think I could make the flight…but she was willing to try. “Sir, can you run?”

Oh, yes! First to the police kiosk, drop the rifle and ammo, then to the security line. Amazingly, that young ticket agent met me there and steered me through diplomatic clearance! Saying, “Sir, now we must run,” she grabbed my computer bag and took off on ridiculously long legs.

Huffing and puffing, I managed to keep her in sight…barely! The bank of gates for most African flights is down a long set of stairs flanked by up/down escalators. The young lady hit the crowded down escalator. I hit the stairs and passed her…just as they were calling my name on the loudspeaker. I shouted my name and spotted the gate as I flew down the stairs. The boarding area was empty, the bus outside full—but Haldane was at the door, chatting up the gate agents, a delaying action that probably kept those doors open for extra moments.

Amazingly, all my luggage arrived on the plane with me. Clearance in Beira was no problem and the charter flight was waiting. Before noon the next day I shot a fine old buffalo bull, so I guess I had the last laugh!

I will never travel on Iberian Airlines again. However, in retrospect, my travel agent was trying to save me money, so I accepted a risky itinerary. I know better, so it was really my fault. An extra overnight in Johannesburg, a new charter flight, and the loss of at least one hunting day would have been costlier. Delays happen anyway; so long as you have communications it’s always possible to “make a new plan”—but with all international travel, and especially with firearms, it’s wise to play the “what if?” game.

Just the day before I lost an all-day battle with Iberian Airlines and had to enter South Africa, get a gun permit, and recheck onward to Mozambique. Against major odds it worked, I made the flight, and early the first morning took a fine old buffalo. I got the last laugh—I guess—but it was much too close.