A forty-year dream of taking a bighorn sheep leads to the hunt of a lifetime in Idaho’s Salmon River Country.

I first became obsessed with bighorn sheep when I was a young boy. Every year my family would pack up our camper and head west from our Iowa home to the Rocky Mountains for a vacation. When I was about ten years old we found ourselves in Yellowstone, hiking up to the summit of Mount Washburn. I was ahead of the rest of my family, just trucking up the hill. I topped a small rise when a noise quickly caught my attention. I lifted my head and there a few yards away stood a mature bighorn ram. I ran down the mountain and yelled to my dad, “Dad! Dad! Bighorn sheep! Thousands of them!” I dragged my dad up the mountain to the rise and there stood, well, not thousands, but three bighorn rams. I was hooked.

After moving to Idaho in my late twenties I began putting in for bighorn sheep draws in several states, only to endure nineteen years of “sorry” letters. I was preparing to put in for the Idaho draw in 2016 when my fourteen-year-old son, Logan, said “Dad, I want to put in for sheep this year.” I decided to put us in together for the draw, figuring maybe Logan’s new blood would buoy my chances. Still, there are only four tags available in the unit I put us in for, and I knew the odds of being drawn for two of them were very slim.

A couple of months later I received a message from one of my friends that he had drawn an Idaho mountain goat tag. I congratulated him and then remembered the sheep draw. I punched in my number on the Fish and Game website, closed my eyes, took a deep breath, and hit “enter.” I slowly opened my eyes and was met with “Congratulations!” I was in disbelief. I punched in Logan’s number and saw, “Congratulations!” It was unbelievable–we had both drawn once-in-a-lifetime bighorn sheep tags!

Since the unit was right by our house in Idaho’s Salmon River country, Logan and I began taking the entire family on our nightly scouting trips. I felt fortunate to be able to share this experience with my family, but scouting with a two-, four-, six-, and eight-year-old in tow does have its challenges. We had a ball, though, and having the kids bugging me throughout the day–“Dad, is it time to go sheep scouting yet?”–warmed my hunter’s heart.

The sheep scouting crew.

I also asked my rancher neighbors to keep their eyes out for rams. My friend and neighbor Preston Cutler told me a spot to check, and the next night we headed out. I unloaded my crew of young sheep scouts and began to glass. I had barely put up my bino when I spotted six rams. I set up the spotting scope and could see there were two small rams, three medium rams, and one that dwarfed the others in both body size and horn. We watched, took pictures, and filmed them until we started running out of light.

Every night for a week we went back, but we never saw the rams again. I decided we should try the other side of the mountain. After getting to the top of the mountain I got the kids situated and began glassing. Nothing. I glassed for over an hour and we were just getting ready to head out when something caught my eye. I put the scope on it, and sure as heck it was a ram. I soon found the other five. The big ram was still with the band and I got a better look at him. Definitely a shooter, and three other rams in the band were as well, though they were not of the big ram’s caliber.

I scouted other areas but didn’t find anything of interest. On one scouting trip about three weeks before the season, on my own and several miles back in the middle of nowhere, I wrecked my motorcycle on a wet log in a rainstorm and wrenched my knee. I thought I had broken my leg at first, but after gathering myself soon realized it was my knee and that I could put no weight on it. I struggled to get the bike upright and carefully made my way out to my truck. My hunt was in peril and I began to think about how I could get Logan on the rams without me. I even wondered if I could get permission to forego my tag until next year. Twenty years of trying to draw, and now this. No way. I bought a knee brace and decided I would have to tough my way through it.

Four days before the season opener, Logan and I backpacked in to our camp at 9,500 feet and about a mile from where I had last seen the rams. The next day we set out to find them, in hopes of keeping an eye on them until opening morning. After setting up in a nice spot and glassing for a couple of hours, we heard a commotion below us and saw the rams disappearing into the small timber in the head of the drainage. I feared we had blown it. I hoped they had only caught a bit of our wind in the fickle mountain drafts.

After a tense while we started spotting bits and pieces of the rams feeding on the far side of the trees. The big ram appeared and led them out into a shale slide where he began scraping out a bed. Eventually seven rams worked their way out to the slide and bedded down for the afternoon. We watched them for about five hours as they slept, fed in a small opening with scattered trees, and bedded down again. I was a real treat to enjoy the day with my son in the presence of such majestic creatures high in the mountains. As long as they stayed here, we had an ideal plan for opening morning.

Then all hell broke loose. Rams came busting out of the trees in full panic-flight mode. Down the shale they ran, into the bottom of the drainage, and they were gone. I told Logan I didn’t know what happened, but I guessed that one of them had run into a mountain lion, for we knew no other humans were anywhere near. Dejected, we headed back to camp.

Once in camp we started thinking about what to do. We decided to take the chance that they had only moved one canyon over, and decided to glass not far from camp the next morning.

Up at daylight, we headed to a small island of about five trees looking across into the drainage where the kids and I had spotted the rams a couple of weeks prior. We got comfortable and started glassing as soon as it was light. Logan spotted the rams first in the shale slide across from us. We watched the rams from this spot for twelve hours that day, never leaving the shade of our tree island. I was thrilled and proud to see the patience and maturity Logan showed on this long day. One thing of note was that one of the smaller rams was missing, which seemed to lend credence to my mountain lion theory. Tomorrow was the opener and we had them in the perfect spot. We glassed until we could sneak out in the dark and headed back to camp to prepare for opening morning.

I gave Logan first pick of the rams and he chose a wide three-quarter-curl ram. I chose the big, over-full-curl ram, the leader and king of this band. There was another full curl ram that was pretty but thin-horned, and another that was almost a twin to Logan’s ram, and three smaller rams. Now if our plan would only work!

We were up well before daylight on opening day, excited to be sheep hunting. We moved into our spotter’s nest from the previous day and waited for it to get light enough to see. We soon spotted the rams on the same shale slide where we had left them, but they were higher than they had been the night before. All good so far. Now if they just would move down the slide, we could easily move into a shooting position. As we watched, they instead moved up over the top and back into the drainage they had run from two days before.

Logan and I packed up and headed across a large saddle and across the shale slide to where the rams had crossed. We moved to where we had tree cover and crept over the ridge edge. Nothing. Not a ram in sight. Slowly we sneaked down the ridge to try to find a place to glass from. Then we heard shale sliding, and froze.

Down the ridge to our left were the rams, digging in the shale, just 200 yards away! Slowly we crouched and scooted to a bit of cover and a shooting position. I slid up to a downed log and Logan was to my left. The ram I had chosen was perfectly broadside and in the clear, but the ram Logan had chosen was still obscured by brush. We had decided if the opportunity occurred for both of us to take our rams, we would count to three and both shoot. This would be easier said than done, however, especially with the pressure and excitement of a once-in-a-lifetime ram in the cross hairs.

We waited and waited for an opportunity at both rams until they fed down the slide and out of sight. Had we just blown the only chance we would have at these rams? Should one of us have taken the shot? We stayed put in our position for hours, hoping the rams would return. The sun was beating down on us, cooking us where we sat, with no shade available.

A few hours into our sit, a small ram appeared in the clearing directly below us. Anxiety was at a high again as we got into position, hoping the big rams would follow the smaller ram out into the open. Another small ram appeared, and then they disappeared and the wait was on again. The wind was swirling toward where we thought the rams were bedded. We debated whether to move down the ridge or get out of the drainage completely to keep from spooking the rams.

Eventually Logan stood and crawled up on a log to stretch and instantly exclaimed, “There they are!” The rams were working back toward us across the same slide where we had found them then lost them earlier. We got into position again and they disappeared into a narrow band of timber where we should be able to see their movement in any direction. Nothing. Another few hours passed and with the fickle winds we decided to move to keep from spooking the rams. Just as we stood, we spotted them again in the same shale slide but this time feeding back up toward where we had missed our opportunity nine hours prior.

The ram Logan had chosen was feeding broadside in a clearing but my ram was behind a rise with only his horns visible above the rise. This began a frustrating game of peek-a-boo which went on for half an hour. One ram would present a shot but the other would be obscured, then vice versa. I had known that pulling off a double would be difficult, but this was almost more than we could bear. The rams split, with several going high on a course that would bring them out into the shale in the open, and our two rams coming over the small rise and feeding directly toward us.

Our emotions were on a roller-coaster ride as we had to watch both groups of rams and hope the wind wouldn’t betray us. Our two rams continued to feed toward us, head on, neither offering a shot, now at thirty yards and closing. They stopped just before the trees directly below us. I had the cross hairs on my ram, directly between his shoulders. But Logan had no shot at his ram. This was it. Another few moments and we would be spotted at close range by these rams and blow them clear out of the country.

Suddenly Logan whispered, “Dad, the pretty full-curl ram is broadside. He’s beautiful. I am going to take him if you have a shot on your ram.”

I asked if he was ready and he nodded yes. I whispered, “One . . . two . . . three.”

The mountain exploded with the report of two rifles as one. My ram dropped in his tracks and began rolling down the shale slope. I instantly turned to Logan and asked what happened.

He said, “I’m not sure. He ran straight down the slope.”

We gathered up and moved just a bit to where I could see my ram piled up against the only boulder on the shale slide–he was down for sure. We headed over to where Logan’s ram had been standing. Nothing. I began looking for hair and blood to confirm any sign of a hit and sent Logan down to follow the obvious tracks on the shale. Now I was feeling an odd mix of elation and worry.

Logan reappeared and said, “Nothing. I missed.”

My heart sank. What should have been a moment of complete euphoria–a crescendo and the culmination of a challenging day–now turned to guilt. I was thrilled to have cleanly taken my ram but at the same time overcome with sorrow that Logan didn’t get his.

Then Logan said, “You know, Dad, I’m actually glad it worked out this way. I would have loved to have gotten that ram but at least it was a clean miss and I got to share the experience of you getting your ram, and plus now our hunt isn’t over, which means we get to spend more time together on the mountain like this.”

I’ve never been more proud of my son than that moment. I gave him a big hug and tears welled up in my eyes. I was so proud of his maturity and his respect for the animal and the hunt, and thrilled that he still relished time spent with his father. We headed down the slope to check out the fallen king.

Upon reaching my ram, we were both wearing ear-to-ear grins. I put my hands on the magnificent horns and thanked the ram for giving his life. I have judged many sheep in my life, but I had misjudged this ram. Knowing most of the rams in this unit averaged 14 to 14½ inch bases, I had guessed he would score in the low to mid-170s. But as I ran my hands over this warrior’s battle gear and counted the growth rings on the over-full-curl horns, I knew I had underestimated him. He was truly an exceptional ram and befitting a once-in-a-lifetime tag. He was nine years old, with a Roman nose and scars from years of hard-fought battles.

James Reed with his beautiful bighorn ram, taken in Idaho’s Salmon River country.

We sat, absorbing the moment. The mountains were silent now and almost reverent. We snapped pictures, and as the light was fading from the sky I told Logan to prepare for a long night on the mountain. We were both nearly out of water and dehydrated from the long sit in the unrelenting sun during our ten-hour wait. As I dressed the ram, Logan gathered wood for a fire and scouted out a flat spot to camp for the night. He found a nice little bowl about fifty yards above us, which would provide shelter from the wind and be a safe spot to have a fire all night in the shale, and most important, keep us from rolling down the mountain while we slept.

I finished up with the ram about midnight, laid the meat out on the big boulder, and spread the life-size cape out on a fallen tree to cool. Logan had a fire going and we had intended to cook some sheep loins over it but we were both too exhausted and dehydrated to eat. Logan was soon asleep and I simply lay there looking up at the stars, enjoying the moment and time on the mountain. I looked at my son, who, I thought, had transformed into a man on this hunt. I looked at the magnificent ram’s horns, dimly lit by the flickering firelight. I looked at my old friend Orion in the clear night sky, and thanked him for being there on another great hunt.

I knew I was in for a long, chilly, uncomfortable night, but as a tear ran down my cheek, I knew in truth the night wouldn’t last long enough. Then it occurred to me: We still had another sheep tag to fill.

Leave a Comment

Incidents from an Elephant Hunter’s Diary: This book of W.D.M. Bell’s newly discovered, never-before-published short stories is a delight. Once again the legendary hunter marches through the wilds of Africa, traversing a land untouched by modern civilization in search of adventure and ivory.

Incidents from an Elephant Hunter’s Diary: This book of W.D.M. Bell’s newly discovered, never-before-published short stories is a delight. Once again the legendary hunter marches through the wilds of Africa, traversing a land untouched by modern civilization in search of adventure and ivory. taken on the Dark Continent includes elephants, buffalo, the big cats, spiral-horned antelopes and dozens of other magnificent animals. Top five SCI and Rowland Ward trophies as well as historic, unlisted, and little-known trophies are included—read their fascinating stories here.

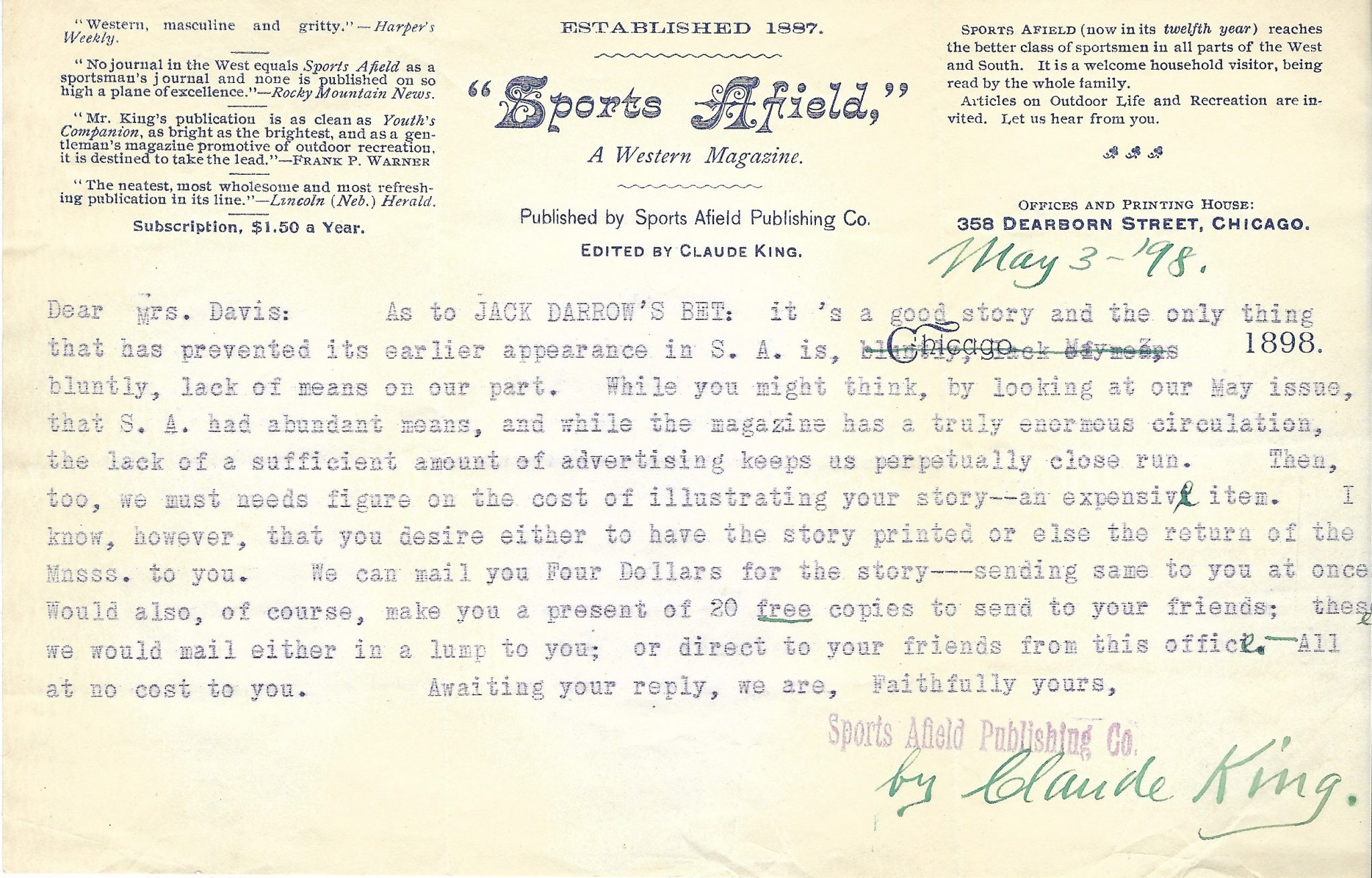

taken on the Dark Continent includes elephants, buffalo, the big cats, spiral-horned antelopes and dozens of other magnificent animals. Top five SCI and Rowland Ward trophies as well as historic, unlisted, and little-known trophies are included—read their fascinating stories here. Celebrating 130 Years of Sports Afield: Just in time for Sports Afield’s 130th anniversary, the magazine’s staff has assembled a complete history of the publication. The book features more than 400 beautiful handpainted covers, all digitally restored. A historical overview of the magazine on a decade-by-decade basis and period articles from each era complement the covers displayed in the book and give readers a glimpse of the sporting life in America through the years.

Celebrating 130 Years of Sports Afield: Just in time for Sports Afield’s 130th anniversary, the magazine’s staff has assembled a complete history of the publication. The book features more than 400 beautiful handpainted covers, all digitally restored. A historical overview of the magazine on a decade-by-decade basis and period articles from each era complement the covers displayed in the book and give readers a glimpse of the sporting life in America through the years. sheep and goats. Since then he has hunted on five continents and eleven countries. Come travel with Latham as he hunts the Rockies, the Caucasus, Siberia, and New Zealand. Here is a mountain hunter who has done it all and tells the stories well.

sheep and goats. Since then he has hunted on five continents and eleven countries. Come travel with Latham as he hunts the Rockies, the Caucasus, Siberia, and New Zealand. Here is a mountain hunter who has done it all and tells the stories well.

Craig Boddington has been named the 2017 Weatherby Award winner. The Weatherby Award is a prestigious hunting award that is based on these criteria: the number and quality of the collected species, the amount and type of conservation effort put forth by the individual throughout his/her lifetime, and the hunter’s personal character, hunting ethics, and integrity. It takes dedication, sportsmanship, a high level of ethics, and over-the-top hunting accomplishments to win this award. Craig, as the 61st Weatherby winner, has joined the ranks of the privileged few ever to attain this pinnacle in the hunting world.

Craig Boddington has been named the 2017 Weatherby Award winner. The Weatherby Award is a prestigious hunting award that is based on these criteria: the number and quality of the collected species, the amount and type of conservation effort put forth by the individual throughout his/her lifetime, and the hunter’s personal character, hunting ethics, and integrity. It takes dedication, sportsmanship, a high level of ethics, and over-the-top hunting accomplishments to win this award. Craig, as the 61st Weatherby winner, has joined the ranks of the privileged few ever to attain this pinnacle in the hunting world.