Hunting the elusive Coues and Carmen Mountain whitetails.

It’s early February and I’m in northern Mexico, one of the best places on Earth in late winter. Mornings are brisk, midday sunny and pleasant under a cloudless sky, bright campfire at night. I’m hunting Coues whitetail, the grey ghost of southern Arizona and northwest Mexico. I’ve been at it for three days, haven’t seen a good buck yet. Maybe I will, maybe I won’t, really don’t care. Love the desert mountains this time of year, and these tricky little deer are one of my all-time favorite pursuits.

Like so many of my generation, I first read about them in Jack O’Connor’s Game in the Desert(Derrydale Press, 1939). The Professor made hunting these crafty little deer sound like so much fun. Today we mostly hunt Coues deer by painstaking glassing. In O’Connor’s Arizona days, they were more commonly hunted by riding horseback through good habitat, jumping deer, and bailing off the horse to get a shot. Late in his life, I was fortunate to know great Coues deer hunter George W. Parker. Between 1926 and 1969, Parker put an amazing seven Coues bucks into B&C’s all-time book. George described his early Coues deer hunting just like O’Connor: Jump-shooting from horseback. I don’t know if there were more deer back then, but I’m sure the shooting was even more difficult than they described. Especially since much of their hunting was with iron sights.

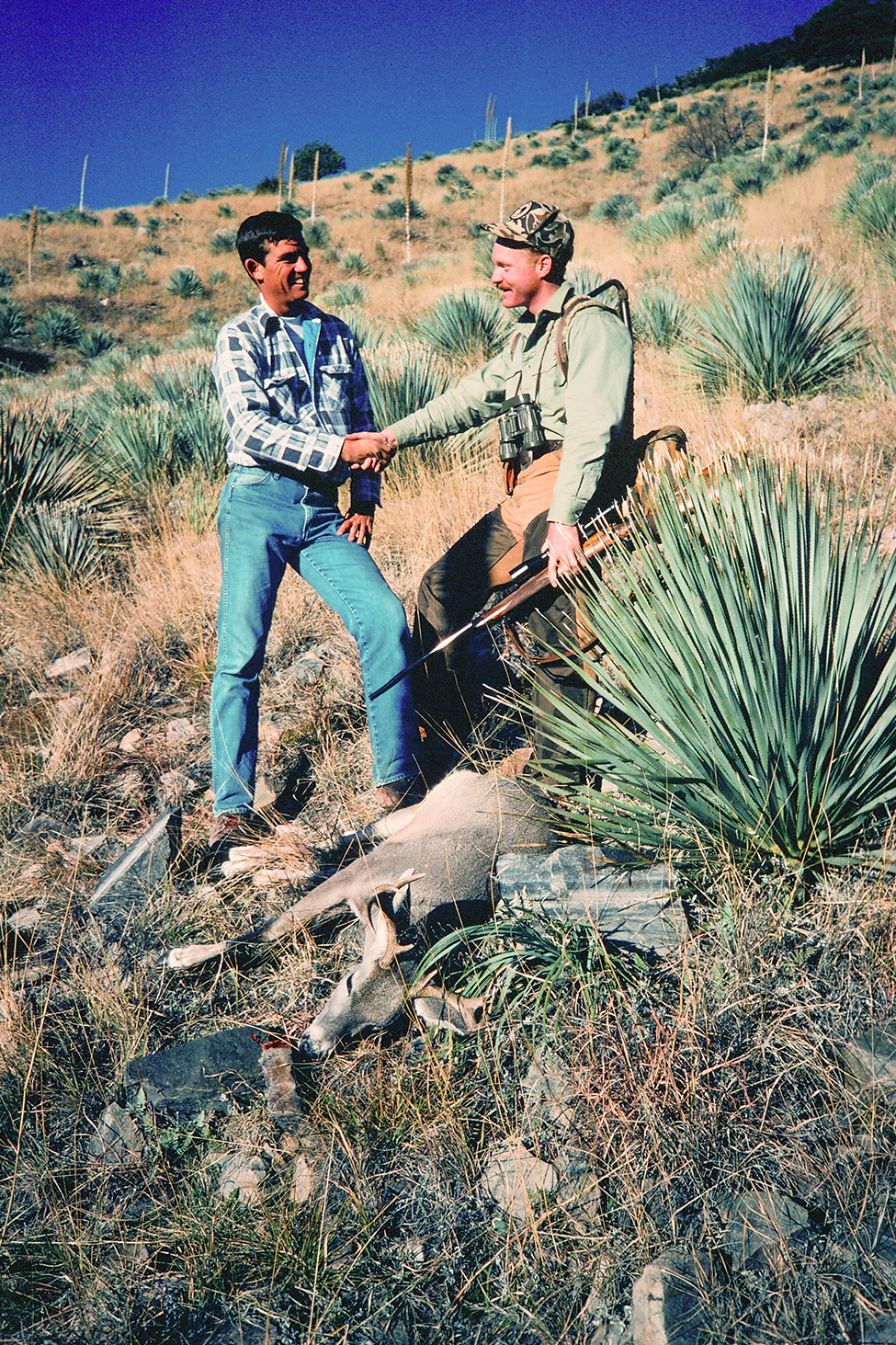

I first hunted Coues deer in the fall of 1978, with Marvin and Warner Glenn out of Douglas, Arizona. Marvin is gone, but the Glenn family is still famous for their sturdy riding mules. Although the Glenns did plenty of glassing, I got my first Coues whitetail just as Parker and O’Connor described. Late in the hunt, we were riding up toward a saddle, Marvin in the lead, when he jumped some deer and vaulted off his mule. I hustled, got a quick shot at a nice buck just as he topped out. I rushed the shot, didn’t hit him well, but we caught him moving around a bowl over the rim and I got in a finisher.

I did more hunts with the Glenns, then studied post-graduate Coues deer glassing under great Arizona hunter Duwane Adams. I loved the Arizona hunting, was usually successful…when I drew. Not drawing drove me to Mexico, often with Kirk Kelso. Several times in Chihuahua, more frequently Sonora. The B&C book suggests that the biggest bucks come from Arizona. Probably true, but Arizona is mostly public land and hunting pressure is greater. I’ve never had huge trouble finding Coues deer in Arizona, including recently on BLM land adjoining son-in-law’s ranch north of Phoenix. However, in Mexico, legal nonresident hunting is on private (or communal/tribal) land. Success is higher, average size better, although Arizona’s top end bucks are probably bigger. Whatever, I love to hunt in northern Mexico. Like the feel of the remote ranchos, love the home-cooked Mexican fare, enjoy the people (I wish my Spanish was better).

Army surgeon and naturalist Elliott Coues “discovered” his small, grey deer in the Department of Arizona during the Apache Wars. So different from the “Virginia deer,” it was believed a full separate species well into the Twentieth Century. Today, Odocoileus virginianus couesi is accepted as just one of (arguably) thirty-eight whitetail subspecies, twenty-nine in North and Central America. In Boone & Crockett’s Records of North American Big Game, only the Coues deer is singled out with separate category. Fine by me, but it’s important to appreciate that this special treatment is based on tradition and taxonomic error.

The Coues deer is not the only whitetail subspecies unique to the American Southwest and northwestern Mexico. The other is the Carmen Mountain whitetail (O. c. carminis), after the Sierra del Carmen range in western Coahuila. This whitetail is not nearly as well-known as the Coues. Safari Club International’s record-keeping system now recognizes it, along with several other Mexico-unique whitetail races, and it’s part of the collection of all of Mexico’s deer, a most difficult task that many Mexican (and a few crazy Americans) strive for.

The carminis, or del Carmen, locally called “fantail” in Texas, is essentially the whitetail of the Big Bend region, the huge Park itself, and peripheries in both Mexico and US. As O’Connor’s writing drew me to Coues deer, it was early reading that drew me to del Carmen, When I was young and only dreaming about this stuff, Hal Swiggett wrote a story about hunting whitetail, desert mule deer, and “fantail” in West Texas. Wow, three kinds of free-range deer in one area? The Carmen Mountains whitetail went on my bucket list, right next to Coues.

Today I know that, even as big as Far West Texas ranches can be, it’s unlikely to have two pure whitetail strains in one place. Almost all whitetail races have broad hybrid zones. Still, the Carmen Mountains whitetail is a real and unique Southwestern deer. In Texas, found in and around the Big Bend National Park. In Mexico, del Carmen has perhaps the smallest range of any of Mexico’s whitetails, restricted to western Coahuila.

North and east, they bump into Texas whitetails; west and south, into Coues deer. Carminis and couesi are both smaller races, hunting conditions much the same, low densities in country with spikey plants, crumbling rock offering terrible footing. Although I’ve done much Coues deer hunting, I know less about del Carmen. However, being that guy, interested in the unusual, I’ve hunted them in both Texas and Coahuila.

We think of them as similar, but this is a disservice to both deer. There are similarities, also differences. Compared to northern whitetails, both have larger ears and outsized tails, for heat dissipation in their warm climate. When raised in alarm, it’s that big, luxurious tail that gives the Carmen Mountains deer its nickname “fantail.”

Del Carmen is larger than the Coues deer and can grow larger antlers. This might seem misleading, because their range in Texas is harsh and dry, almost certainly reducing body size and antler growth. In western Coahuila the country changes dramatically. The Sierra del Carmen range has significant forest, and grassy valleys below are popular for breeding horses. Western Coahuila’s softer country has potential for larger deer.

Visually, the Coues deer is very grey, while the Carmen is brown. It also seems to me that Carmen antlers are more typical, straighter lines and smoother curves, while Coues antlers seem to often form in kinky curves and are rarely perfectly matched one side to the other. In both size and appearance, it seems to make sense that Carmen deer are more like the Texas whitetails they adjoin, while the more distant Coues deer show greater differences.

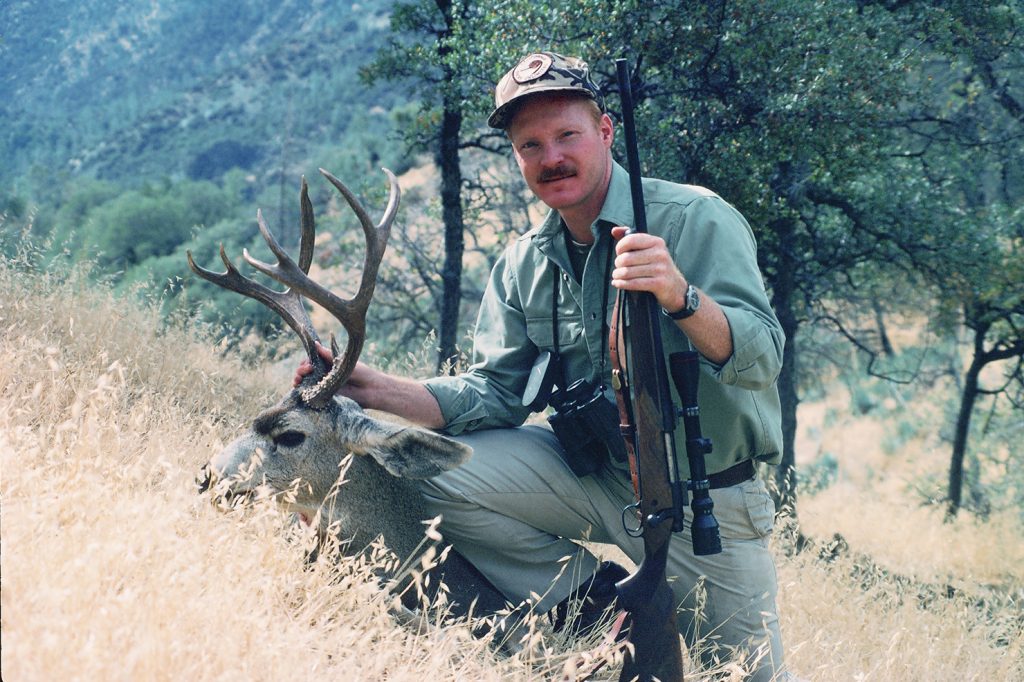

My first hunt for del Carmen was with Steve Jones in the Chinati Mountains west of Big Bend. In Texas the fantails share their country with free-range aoudad, so this was a marvelous combo hunt. Lots of aoudad, fewer deer. One afternoon we glassed up a nice eight-pointer. We had him in the spotting scope, waiting to see what he did before making a move. He was walking along a little rimrock far below us and I guess he stepped into a bedded aoudad ram that materialized into the field of view, one of the most amazing sights I’ve seen through a lens. The buck dropped off the rim and out of sight, so I slipped down and shot him.

I went into Coahuila with New Mexico outfitter Jess Rankin. Much different, better-watered country. We saw few deer, although we took a nice buck. Depends on where you are; Mexican friends tell me some ranches have high numbers. One thing the area did have: Plenty of black bears, killing horse foals on that ranch. Among Mexican hunters, it’s axiomatic that black bears and Carmen Mountains whitetails go together.

Whether carminis or couesi, intensive glassing is the primary technique. Small deer, thinly dispersed in big country. Patient glassing with the biggest and best optics. I’d almost call glassing the only technique. Except: In some situations, waiting over water sources can be effective. I’m at Buelna Ranch in Sonora with my friends, brothers Andres and Santiago Santos. We spend some time at waterholes here. Also, unusually, in this area whitetails are often found out on the desert floor as well as in the hills. So, we do some cruising from high racks for both whitetails and desert mule deer. Still, glassing remains the preferred method. This afternoon we’re going to climb a ridge and glass an enticing canyon until dark. There’s lots of sign–must be a big buck in there. Maybe today will be the day.