Great ideas for fun things to do before and after your safari in South Africa.

In the past when a non-hunter went on safari, there usually wasn’t much for the companion, or observer, to do except trail along with the hunter, sit in camp with a good book, or, where available, go with a camp employee to visit villages or shop.

Times have changed, though, and these days there is a wealth of opportunities for adventure in Africa. This article will take a good look at some of them. South Africa is a common destination for hunters, so we’ll start there and cover some of the side trips, mini-vacations, and travel destinations in that country. We will also discuss how hunting lodges have changed over the past decade or so.

Then and Now: Hunting Lodges I went on my first African safari in 1995. I stayed in a tent in the bush where the shower was operated by a young boy filling a five-gallon bucket with water that had been heated over an open fire. To wash, you called “shower” and the bucket was lowered down by rope and pulley, then filled with water that smelled of the wood in the fire. The bucket had a shower head attached to the bottom, and you showered by turning on the valve, getting wet, shutting off the shower head, soaping, and then turning the valve back on to rinse off. The tents were tastefully furnished with a bed, a dresser, and that’s about it. Mine was additionally adorned with a bright blue spider that lived up high where the sides joined the roof. My wife didn’t care much for this decoration, but I managed to calm her nerves by saying, “Don’t worry about him living up there. ‘Course you might want to be a little concerned when he’s gone.” For some reason, it got very cold in the tent that night.

Meals were cooked on a 3’x3’ steel plate placed over one corner of the fire pit. The cook could do anything from fresh bread to kudu steaks on that plate – and it all tasted wonderful. The food’s taste wasn’t harmed at all by the few ashes that managed to collect on whatever was on the menu.

These days, things have changed. Bathroom facilities are much improved. Safari camps are more likely to be lodges, and have much more for a non-hunter to enjoy. There are guided day trips to local villages and towns, animal viewing and photography, dancers around the campfire, swimming pools, and the food service is excellent – even the steel plate is gone. South Africa South Africa offers something for everyone. It’s modern cities have excellent dining and a thriving art scene. There are diamond mines to visit, vineyards to sample, mountains to climb, and huge game reserves like 7,523 square mile Kruger National Park (3.5 times larger than Delaware.). There are seventeen different regions in South Africa, and we’ll see what each one has to offer. We’ll look at half of them in this post, and then cover the remainder in a later one.

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula. It’s a 19,000-acre section of Table Mountain National Park. Contrary to common thinking, the Cape is not the southernmost point on the African continent. That honor belongs to Cape Agulhas, 90 miles southeast. The Cape of Good Hope is home to numerous animals, including the bontebok, red hartebeest and eland. Chacma baboons are the animals most associated with the Cape, and are a major tourist attraction. There are miles of hiking trails and many beautiful deserted beaches. The Cape is the legendary sailing waters of the Flying Dutchman, a storied 17th-century ghost ship crewed by long-dead sailors. It is cursed to sail the ocean forever.

Cape Peninsula

When in Cape Town a round-trip drive down Cape Peninsula makes a great side excursion. The trip takes you along the False Bay coast where you can visit Kalk Bay, a small fishing village, and Boulders Beach, a sheltered beach between granite boulders near Simon’s Town. The beach is home to jackass penguins that live on the protected beach. The rugged coastline along the peninsula is one of the most scenic in Africa. Take a drive along the Misty Cliffs, located between Scarborough and Witsands, where you can windsurf or kite surf. Don’t forget the sunblock.

Horses and camels can be rented at Noordhoek Beach. Sometimes whales are visible, and seals and otters are common. There are many cottages and B&Bs to stay at, and there are a number of cottages available inside the Cape Point Nature Reserve on Olifantsbos Beach. While there, hike the shipwreck trail in company with the local bonteboks. Checkout the remains of a Dutch coaster that wrecked there in 1963.

Dolphin Coast

The Dolphin Coast (North Coast) on the northern coast of South Africa is located less than one hour north of Durban in KwaZulu-Natal Provence. It’s on the Indian Ocean, and is bordered by the Tongaat River near Ballito and the Umhlali River. It’s known for its large pods of bottlenose dolphin right offshore.

Durban and KwaZulu-Natal

Durban has some of the most beautiful beaches in the world. They extend all the way to the Dolphin Coast to the north, and down the Sapphire Coast into the Eastern Cape. KwaZulu-Natal has two World Heritage Sites – the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg Park and iSimangaliso Wetlands Park. It’s also the location of the battlefields of the Anglo-Zulu and Anglo-Boer wars. Historical sites include Isandlwana, Blood River, and Rorke’s Drift.

Mpumalanga and Kruger National Park

Mpumalanga (where the sun rises) is South Africa’s wildest province. It consists of both Highveld and Lowveld. The southern half of Kruger National Park is in the latter region. Other major tourist attractions include the Sudwala Caves and the Blyde River Canyon. Kruger National Park and surrounding private game reserves are home to all of the Big Five – Cape buffalo, elephant, leopard, lion, and rhino. Stay at one of the game reserves and you are guaranteed luxury accommodations, excellent service, and lots of African animals just outside your door.

Noordhoek

This area is a suburb of Cape Town approximately 22 miles to the south of the city. It can be reached from the spectacular coast road, Chapman’s Peak. It has a picturesque shoreline and a long pristine white beach. The century-old wreck of the steamship Kakapo is on the southern end of the beach.

South Coast

The South Coast area of KwaZulu-Natal is a popular destination that stretches all the way from Amanzimtoti beach just outside Durban down to Port Edward. Its 125-mile length encompasses the vacation towns of Margate, Palm Beach, Ramsgate, Scottburg, and Trafalgar. The area has some of the country’s finest beaches backed by natural jungle and palm trees. There are numerous nature reserves, trails, swimming activities, including snorkeling and diving, and two of the country’s best golf courses.

Setting up Side Excursions while in South Africa

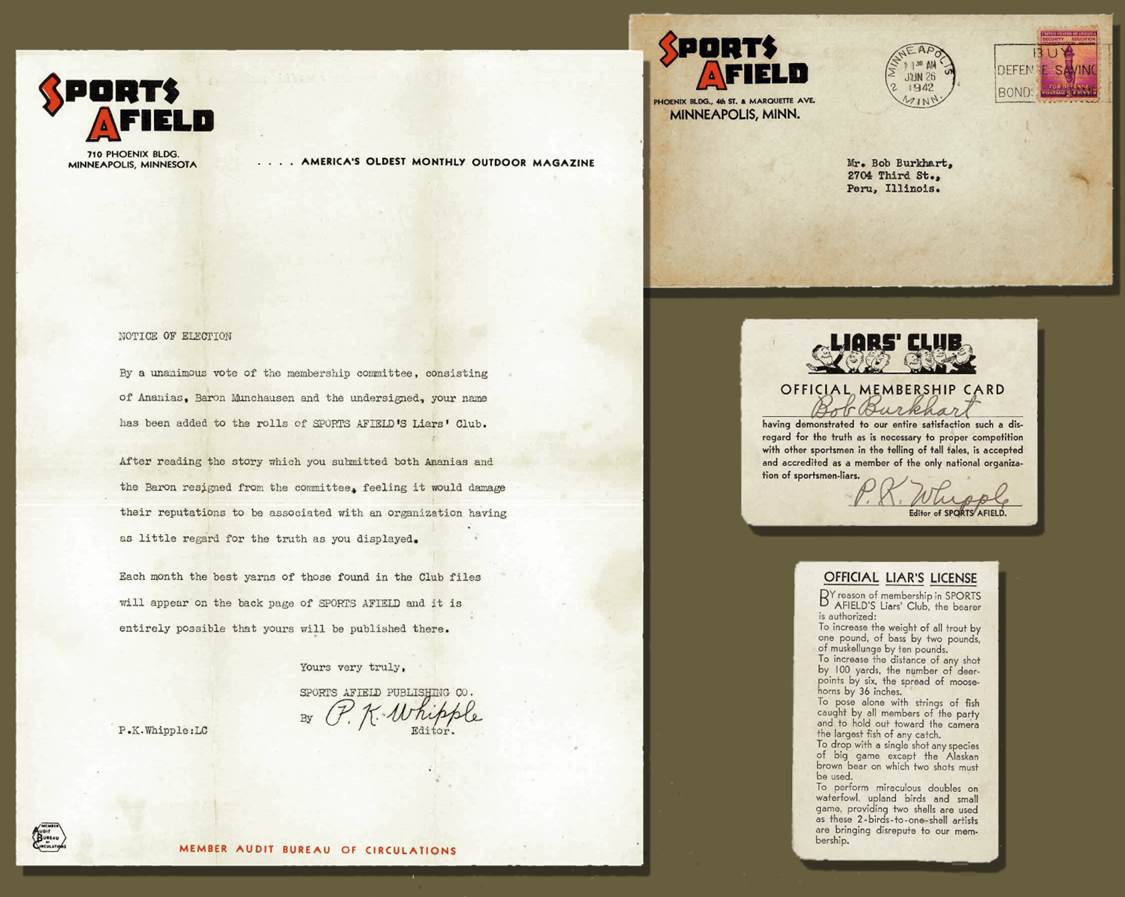

Because most hunters on a South African safari aren’t really familiar with the country other than some of the hunting camps or game ranches, it best that anyone seeking side trips use the services of a hunt broker who is knowledgeable about what’s available. The broker should have references, and a comprehensive web site that answers all your questions. I’ve been working with John Martins at Discount African Hunts: www.discountafricanhunts.com for more than two years. He, and his web site, will provide you with all the information you need for a hunting or camera safari, and can tailor a safari and side trips to your personal requirements.

Below: Bathroom facilities on safari sure have changed over the years! At top, a well-appointed bathroom at a modern safari lodge. Below, a traditional shower setup with a five-gallon bucket.

Most of us know the story of the great sharpshooter Annie Oakley. Born into poverty in 1860 in western Ohio, Annie began trapping before the age of seven, and she was shooting and hunting by age eight to support her siblings and her widowed mother. She sold the game she killed to local shopkeepers and to restaurants and hotels in Cincinnati and northern Ohio. At age fifteen, the revenues from her shooting skills paid off the mortgage on her mother’s farm.

Most of us know the story of the great sharpshooter Annie Oakley. Born into poverty in 1860 in western Ohio, Annie began trapping before the age of seven, and she was shooting and hunting by age eight to support her siblings and her widowed mother. She sold the game she killed to local shopkeepers and to restaurants and hotels in Cincinnati and northern Ohio. At age fifteen, the revenues from her shooting skills paid off the mortgage on her mother’s farm.