Challenges for the International Community

Presentation to the World Forum on the Future of Sport Shooting Activities, Nuremberg, Germany, 8 March 2007

© Diana Rupp, Editor in chief, Sports Afield

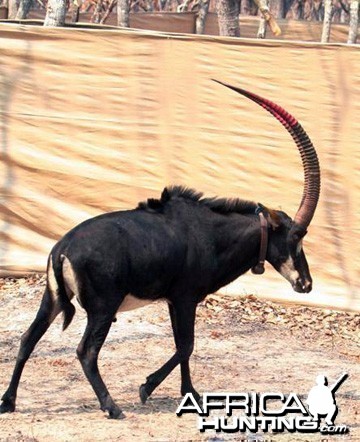

Did you know that without hunters, African animals like the black wildebeest and the white rhino probably would not exist today? Hunting plays an important role in conserving large areas of wildlife habitat in Africa and providing income to people in impoverished areas of the continent. And those of us who don’t even live in Africa will have a major effect in deciding what happens to its wildlife.

Africa has changed more over the past hundred years than any continent in the world, and we can expect it to continue to change dramatically in the course of the next hundred. While we look with concern to the future of this troubled continent and its rich wildlife resource, we can also take heart that Africa today remains the undisputed mecca for the big-game hunter. The question is, will that still be true twenty-five years from now?

The first thing to understand about hunting in general, and particularly African hunting, is that it is more than a recreational activity. Smartly crafted hunting programs serve and save wildlife around the world. Safari hunting is a little different than resident hunting in America and Europe in terms of economics—it brings in huge amounts of money and, where it is well managed, results in relatively few animals taken. Those two things combine to create economic incentives for wildlife conservation over wide areas.

Safari hunting is a significant industry in about a dozen countries in Africa. A 2006 study estimated that trophy hunting generates gross revenues of just over 152 million Euro per year in Africa from some 18,500 visiting safari hunters.

Safari hunting as an industry is growing in southern and eastern Africa and is static or declining in central and western Africa. Five countries—South Africa, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and Botswana, attract the most clients, with South Africa in the lead. It hosts some 8,500 clients each year, about 57 percent of them from the USA, and generates 76 million Euro and more than 6,000 jobs. Namibia is second with almost 5,400 hunters per year, with about 43 percent of them coming from Germany and Austria. If you look at hunting revenue as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product, safari hunting is most significant in Botswana and Tanzania where it represented just over 1/10 of a percent of GDP last year.

There are essentially three types of hunting areas in Africa. On government concessions, such as the one I hunted buffalo on last year in Tanzania, the government leases the hunting rights to an outfitter and receives the money as well as the trophy fees from animals shot. On communal lands, local communities lease their hunting rights to an outfitter and the people and villages receive the proceeds.

Private land hunting is the third type and it is a huge business in southern Africa, where a large scale conversion of livestock ranches to game ranches in the 1970s kicked off a major resurgence in wildlife numbers. In Namibia, the shift to game ranching resulted in an 80 percent increase in wildlife populations during 1972-1992. Today, South Africa has about 9,000 game ranches that are home to almost 2 million wild animals.

It was safari hunting that stimulated that shift to game ranching and the resulting increase in wildlife populations. Common species like kudu and springbok benefited, but so did formerly rare species like the white rhino, the bontebok, and the black wildebeest. In fact, South African game ranchers are credited with being almost singlehandedly responsible for bringing back the white rhino from the brink of extinction. It’s important to note that a well-designed, ethically run game ranch on a property that is large enough to allow animals to escape from predators is not a “canned” hunt. These areas can provide challenging hunting and are a more affordable alternative to traditional wilderness safaris.

Hunting in Africa is a major industry that makes important economic contributions. And it is an important factor in the long-term health of wildlife populations on the continent. But African hunting faces serious challenges in the 21st century—challenges that we in the international community need to address to ensure that hunting continues on this continent for generations to come.

First, We must be sure that local communities have a stake in their wildlife and its management.

Second, We must work with international treaty organizations and with governments in North America and Europe to ease restrictions on the imports of hunting trophies.

Third, We need to educate governments and people in countries that do not currently allow hunting, or where the hunting industry is struggling, and give them the tools and aid to develop hunting programs.

First we’ll address the idea of giving communities a stake in their wildlife.

It won’t surprise anyone who knows even a little bit about Africa that one of the main threats to its wildlife, and by extension to the continuance of legal safari hunting, is poaching. I’d like to share with you an interesting fact: Countries in Africa that allow hunting tend to have good, stable wildlife populations. The countries that don’t allow hunting, such as Kenya, have declining wildlife populations. Wildlife in Kenya’s national parks is doing OK, but these are just small islands of protected land. Since Kenya closed hunting in 1977, wildlife populations outside of the parks have declined between 60 and 70 percent as a result of a huge surge in poaching for bush meat.

One reason this is true is because the modern professional hunter, or safari guide, in wild Africa acts as a manager of wildlife. When he is there, there is somebody who has a vested interest in what happens to the wildlife. Simply speaking, the presence of safari operators keeps poachers out. Whether you’re talking about a villager who is shooting duikers to sell as bush meat in the local village or whether it’s a high-level international poaching ring out for the big money in ivory, having a legal presence out there in the bush—an organized presence with vehicles and rifles and radios–is a major deterrent.

But safari hunting can also be a crucial part of a far more permanent way to deter poaching. And that is to get the community involved and invested with the wildlife that surrounds it. This is one of the most important trends in African hunting right now– the alignment of safari hunting with community conservation and development policies, which are supported by a number of international donor agencies. This happened first in Zimbabwe with the program known as CAMPFIRE.

Under CAMPFIRE, members of local tribal communities living on communal land manage the hunting on their own land. With assistance from the national parks and the World Wide Fund for Nature, the community sets its own hunting quotas and leases the hunting to one or more safari operators. Fees paid by the hunting operator and trophy fees paid by the client are plowed directly back into the community, providing money for schools, clinics, and other necessities so badly needed in most of rural Africa.

Similar programs are going on in other countries as well—Namibia, Zambia, Mozambique, CAR, and Cameroon.

No one is more aware of the need for community involvement than safari operators themselves, and some of them have set up their own programs. The flagship is called the Cullman and Hurt community project, started by Tanzania safari outfitter Robin Hurt and the late Joseph Cullman of New York. For every animal that is hunted, the project gives an additional 20 percent over and above the normal government trophy fee directly to the local village.

Robin Hurt told me recently that he believes the biggest threat to hunting in Africa today is human encroachment—loss of habitat for wildlife. Over the last forty years, on average, human populations in Africa have increased between six and eight fold. That’s why these community programs are so crucial. With this kind of population growth, wildlife must have a tangible benefit to the local community or it will be destroyed.

Hunting in Africa is vulnerable to political developments in the USA and Europe. Pressure from antihunting lobbyists and adverse international conservation policies has the potential to severely restrict the growth and survival of Africa’s sport hunting industry.

The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, or CITES, is the treaty that sets quotas and other restrictions on the import and export of wildlife parts. CITES has of course been extremely important in helping to control illegal trade in wildlife. And, this treaty recognizes the special role of recreational hunting by making exceptions for the export of hunting trophies from countries where hunting is well managed and is doing good things for wildlife.

It’s important that the role of sustainable use continue to be kept at the forefront of CITES discussions. Quotas should be thoughtfully and scientifically based to help countries and species that need help. For example, one of the issues likely to come up at the CITES meeting in the Netherlands this year is the management of the African lion. At the last meeting in 2004, a proposal to list the lion on Appendix 1 of CITES, which could have severely restricted lion hunting, was defeated, and since then hunting groups have been working to spread the word that controlled hunting is one of the most important facets of lion conservation.

The other aspect of this is that individual governments—in North America, Europe, Australia, etc.–may set their own restrictions on the import of hunting trophies, even those on a CITES quota. This can be a major limiting factor on the success of hunting programs in Africa. An example involves Mozambique, where elephant populations are increasing dramatically in some areas, and CITES has decided that elephant hunting is appropriate there and has established a quota of elephant that the country may export. BUT an American hunter who legally takes an elephant in Mozambique is not allowed to bring its tusks home because the USA restricts the import of elephant trophies from Mozambique. Until such restrictions are lifted, Mozambique won’t be able to become a premier safari destination and will therefore struggle to fund its wildlife programs. The fact is, safari hunting in Africa depends on hunters from the United States and Europe traveling to Africa and hunting there. And if they can’t take their trophies home, they won’t go.

This issue is not limited to the USA–I understand there has been some talk within the European Parliament to ban the import of some CITES-listed hunting trophies into the EU. It’s crucial that as hunters we keep on top of these developments.

It’s encouraging to note that several countries, including Angola, Guinea, and Uganda, are making at least tentative moves to open their doors to hunting. We need to support this trend.

These are countries struggling with political instability, which is so often an issue in Africa. Obviously, a hunting program is not going to work until a certain level of stability has been achieved. But hunters are more adventurous than other tourists. For example, with the onset of Robert Mugabe’s land re-distribution program that caused upheavals in Zimbabwe starting in 2000, regular tourist occupancy fell by 75 percent, but safari hunting revenues only dropped by 12 percent. As an aside, the fact that hunters are still going to Zimbabwe is probably a major reason it still has any wildlife at all.

At any rate, hunting is one of the first industries that can be restored in a country that is recovering from unrest; we saw it happen in Mozambique, where hunting outfitters moved in once the civil war ended in 1992.

Take the example of Angola. Its wildlife has been severely depleted as a result of its long civil war. However, as professional hunters have pointed out to me many times, wildlife has a remarkable ability to recover. Provided the habitat has not been lost, those game populations will grow back. An organized hunting program helps with this by providing legal protection and money for recovery. Most people I’ve talked to believe that hunting will re-start in Angola, and in fact, the Hunting Report newsletter just had a report on preliminary work done by an outfitter who hopes to start hunting commercially in Angola in about two years.

Kenya is once again talking about re-opening hunting, but that country faces tremendous resistance from anti-hunting groups.

Something that would help these struggling countries with their efforts is more independent scientific research into how hunting helps African countries economically and ecologically. Science is on our side; in fact I just read an interview with a scientist from the University of California who used to be anti-hunting but had totally changed his position as a result of his extensive research into biodiversity in Tanzania. That shows the facts speak for themselves.

In conclusion, there are many healthy trends in African hunting. The affordable private-land hunts in southern Africa are drawing more American and European hunters to Africa than ever before. In more remote areas, programs that help local communities co-exist with wildlife and benefit from safari hunting means that both African wildlife and African people have a fighting chance to improve their lot. And the support of the international community can help to ensure the future of African hunting is a long and bright one.

The more safari hunters who travel to Africa, and the more Africans who derive a tangible benefit from their presence, the better. Together, they represent a powerful coalition of conservationists who care about African hunting and who will be our allies in the fight to support the sustainable use of wildlife on the entire continent.

Leave a Comment