In pursuit of a striped stallion in the rocky highlands of the Namib Desert.

At the farthest edge of the Namib Desert is a land that seems caught in a different time. Game roams free. Water is scarce. In this forsaken place, some of the first Bushmen, Ovambo, Kavango, Wambu, and Herero peoples left their footprints in the rocky sand. Little remains save remnants of Stone Age tools and cliff paintings, yet descendants of those tribespeople today stand watch over the same terrain that now holds the riches of gold below ground and rare marble above, jutting like tumbled dice from towering hills.

This land is hardly untouched; the evidence of human encroachment is unmistakable. Massive blocks of white, gray, and blue marble line the first few kilometers of dirt track leading into one of Namibia’s best-kept secrets. But past the antiquated mining machinery, wickedly dangerous stone cutters, and large trucks hauling stunning cubes of future countertops and towering columns destined for the United States and China, lies another world rich in adventure and challenge. Those who make a living here still find greater value in a hindquarter of game meat than in a ton of pure marble. We were able to gain access to pursue the elusive Equus zebra hartmannae in its wild home, so long as we’d provide our hosts with an animal for meat.

In what seems the center of another world and perhaps another century, far beyond the active mines, Hartmann mountain zebra scale the rocky mountain faces with a grace and ease I can only admire as I struggle with my every step to climb the loose, rocky kopjes. Shards of shale slip out underfoot and tumble down the slope. They tell me these are not truly “mountains,” but I’d respectfully disagree. Though we were out long before dawn, we’d yet to spot the mountain-named zebras in the lowlands where they’re thought to spend the earliest morning hours before heading up toward cloudless heavens.

Outfitter Stephen Bann climbs surprising well for a hulking man with the build of a former rugby player. From the summit, he said, we could glass for game. With a lever-action Henry slung over my shoulder, a bino chest rig, and a backpack, finding my balance took more effort than scanning for game. The zebras were not our only pursuit–gemsbok and kudu were also on the list–but it was the stark black and white animal that drew me here. Once at a comfortable height to survey the surrounding valleys and farther crests, Bann and I settled in.

Among many species of Equidae, the Hartmann mountain zebra shows several notable characteristics. In addition to thin, tight contrasting stripes, the belly is free from such pattern, being mostly white with striping ending a good three inches above the abdomen. Unlike other zebras, the Hartmann’s legs are striped right down to their hooves. In addition, and more difficult to notice at quick glance, is a small dewlap on the neck.

These agile climbers not only exist but thrive in rugged and arid conditions. Water here is scant and unseen, piped in for many kilometers to the mines, feeding the machines cutting marble. Where the zebras find drinking water, much less the people, I still can’t say.

Hartmann mountain zebras travel in much smaller groups than the far more common Burchell zebras. We’d spotted a zeal of three and another of five several days prior, but catching up to them again proved an impossibility. My goal of harvesting one of these wily creatures with a .45-70 Government-chambered lever action was making this venture even more difficult, and while I’m sure my more limited range irked Bann and the diligent trackers, they said nothing. Since I was shooting a 300-grain hunk of lead with arc-like ballistics, we’d have to get close, inside of 200 yards, ideally. Bann wanted to leave nothing to chance and shouldered his own .300 WSM in case I’d need to stretch my ballistic legs.

We’d left Namibian outfitter Brink Grobler of big leopard fame along with fellow hunter Jerry Hnetynka with the Land Cruiser, and they’d gone off in search of cat spoor for their own hunt. Our quick-to-smile tracker, Tomas, summited along with us, though at this particular moment, he was far ahead, about to crest another mountain to the north. He moved with the ease of those who seem built for this land while the rest of us merely come to break ourselves against it. Bann and I glassed low and high, scanning what seemed miles of expansive valleys, stony outcroppings, and far off, as in a mirage, the blazing red of open dunes. One would think–as I mistakenly did–that spotting zebras, their colors in stark contrast to literally everything else here, would be a snap. After all, black-and-white doesn’t seem a practical camouflage.

“Take a break for a moment,” Bann said as I lowered my binocular. He was gazing into the distance and smiling. “Just look around. Isn’t this place beautiful?”

He was right. I had been so focused on looking for a zebra–and not tumbling down the slope–that I’d nearly lost sight of the prize. One could sit here for hours, days even, and never cease marveling at the lonesome beauty of this wild place, thinking how few over the centuries had marveled at this same view.

Our moment of solitude was broken by the faint whistle and waving arms of Tomas. Bann was on his feet and moving down the slippery grade before I could even shoulder my pack. “Come quickly! He’s seen a stallion.”

Down we went, far faster than seemed prudent. I was certain if I survived the way down, as we begin the subsequent climb to where Tomas waited in a crouch behind boulders, I’d be breathing too heavily to place a quick and accurate shot. As we worked closer, Bann motioned to stay low. The two men whispered in hurried Afrikaans and I understood enough between broken words and body language to know it was time.

“A group with a shooter stallion is over the ledge here,” Bann said, gesturing up, “but they’re working higher. Drop your pack and be ready.”

We crawled ahead of Tomas now, slipping alongside one outcropping and hiding behind another, feeling gravel grind underfoot and stepping lightly to silence it. “There!” Bann hissed.

I followed his stare, yet didn’t immediately see anything. “The stallion is in the rear. Get on him,” he ordered, motioning for me to use the rock in front of us as a shooting rest.

I had taken my jacket off and balled it up as a makeshift sandbag and had my rifle ready, but I’d yet to lock onto my quarry. How could I not see an entire group of black and white animals? Bann guided my gaze higher and there I caught a hint of movement, hardly more than 100 yards away but angling upward. I couldn’t believe how naturally they became part of the mountain.

“Track them in the scope,” Bann whispered, “and wait for them to stop. Take the biggest one.” Just when I was afraid I’d never pick them up before they crested the next ridge, my optic came alive. Four zebras were scaling the slope with the ease of mountain goats, not hurriedly, but not stopping either, partially obscured from time to time by dry brush or jutting shards.

The distance was widening as they continued their graceful ascent, but I didn’t dare avert my eye from the riflescope to verify range. “One-twenty-five,” Bann whispered, as if reading my mind. I knew that was meters, and not yards, as I was accustomed. Only a few steps farther, as if hearing his cue, the lead mare paused and looked, not at us, but upward, in the direction they were traveling. The others followed suit and my cross hairs dropped back, finding the biggest body bringing up the rear. The size comparison wasn’t even close. The stallion had been hanging back.

“Now,” said Bann. “If you’re on him, shoot!” The hammer on my Henry All Weather was already back and the trigger broke just as he finished saying the word. The recoil of that 150-year-old chambering took me off the target, and by the time I levered in another round and settled back onto my jacket for a follow-up shot, all I saw was the flash of a striped rear going over the crest and out of sight. My heart was about to drop, fearing I’d botched the shot of which I’d felt so certain just a second ago, but then Bann was pounding me on the back and Tomas–running to us now–let out a hoot.

“Did you see, Memsa?!” he exclaimed as he spun around and pounded one hand down against the other, grinning ear to ear. Though I’d lost sight of the stallion in the outcroppings above and ahead, both men reassured me he was there.

As Tomas set off with his small knife and a machete he’d been carrying precariously tucked in the back of his belt, Bann and I gathered our gear, though I was too giddy to focus. Many months of dreaming had come to fruition in this magical place.

Bann attempted to radio the truck, but didn’t get an answer, so he could only hope they’d heard the shot and would be heading our way sooner than later. And he was correct; just as we had descended, slid, and otherwise not so gracefully made it down one incline and were about to start up the next, we could make out the jostling shape of the Cruiser picking its way around jagged hazards in the distant valley.

“Have you got one, then?” Brink questioned before the wheels had even stopped. I was sure my grin told the tale, but Bann indicated the direction to Brink while speaking quickly in Afrikaans. Plans were in the works, no doubt, when Jerry hopped down from the back. “Well, let’s go see what you got!” he said, throwing his arm around my shoulders.

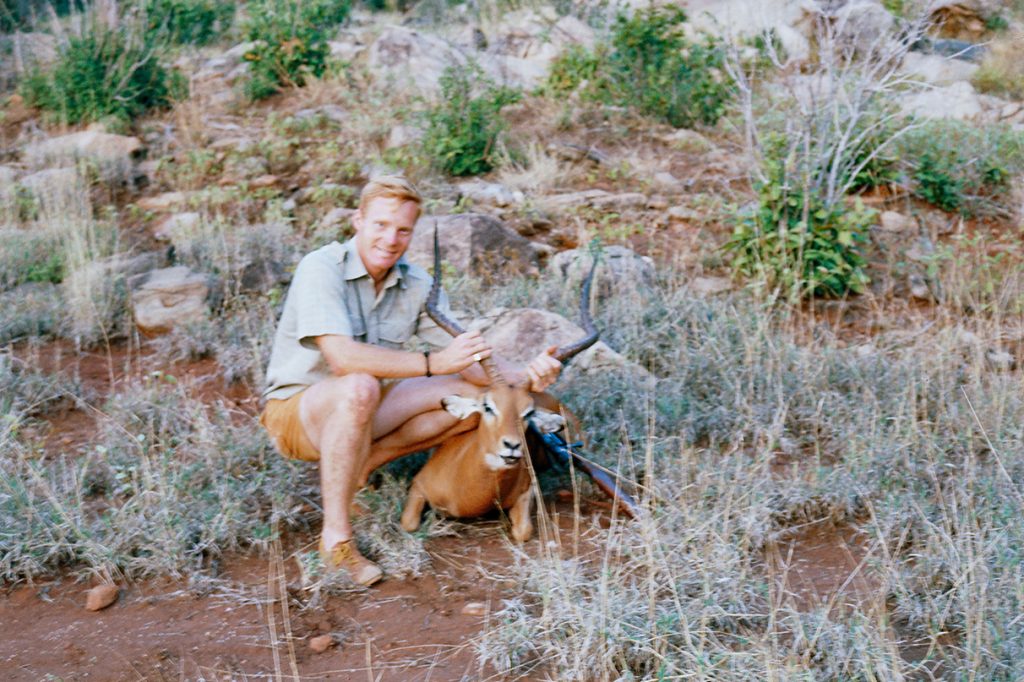

Though the incline didn’t appear that steep from below, my breathing was labored before the muscular creature came into view, and I wondering just how we’d get every ounce of this prized meat back down. When we four reached the tracker, Tomas had already cleared an area for photos, dusting away blood, but he couldn’t budge the animal and sat resting on his haunches.

“Ooh, he’s beeeg,’” he proclaimed as I knelt to rest my hand on the stallion’s thick neck. As I offered a silent prayer of thanksgiving, I couldn’t help but swallow back tears of joy, at once overwhelmed with the surroundings, the people, the history, and our fine little hunting party. We’d overcome a number of struggles and failures in the past few days, making success that much sweeter.

It took all of us to drag the big male a few yards into the clearing. As Jerry and I worked at photos, Brink and Bann were already heading back down to the Cruiser. “He’ll drive back to the nearest miner’s camp,” the outfitter hollered over his shoulder, meaning one of the makeshift tent-and-tarpaulin hovels we’d passed hours earlier. “He’ll fetch some Wambu. They’re strong workers and will come quickly when they know there’s meat.”

Jerry and I did our best to help with skinning and quartering, though I’m still unsure whether we helped or hindered the wisp of a man who was accustomed to working alone, swiftly and without wasted movement. If he was annoyed with our brand of “help,” he didn’t show it and continued about his rhythmic skinning, shifting, and rolling of the carcass, removing the back skin, the hind quarters, carefully saving certain entrails and setting them gently atop the hide. I’d get to keep the cape and skull, but the remainder of the animal would go to the miners. I was already feeling like a million bucks–or roughly 19 million Namibian dollars in this case, a drop in the proverbial bucket compared to the value of the sawn marble, undrilled gold, and desert diamonds that surrounded us.

Before the sun set on this majestic day of perspiration and blisters, I was blessed to take a second, slightly smaller stallion as we descended the mountain. The bakkie was loaded with quarters, capes, and entrails. With barely a place for us to stand atop the Cruiser’s bloodied bed, two Wambu, a Bushman, and Tomas riding on the bumper, all was right with the world. These men had helped pack out all the protein and delicacies two mountain zebras could offer, leaving nothing but the animals’ stomach contents behind. For their assistance, they were given first choice of the cuts they wanted, each opting in turn for pieces of the offal.

I was beyond pleased to have fulfilled my hunting goal, but in those golden moments surrounded by the marble mountains, that ambition felt secondary to other, simpler gratifications. Pleased with the wealth of meat that would supply the camps. Pleased with the palpable excitement of the native workers, not understanding a word of their local dialects but not needing to, either. Pleased that I would soon taste the delights of fresh mountain zebra loin prepared by a native chef over an open flame that night at camp. Bann had explained earlier that mountain zebras, their fat pure white and in stark contrast to that of the more yellow Burchell, was highly prized table fare.

Hot and dusty, resting around a fire that evening, we savored rare-cooked steaks and a few swallows of African brandy, our lives entwined with these treasure-filled wilds, rich with the realization that success comes not alone, but rather, with an unlikely team working in unison. The finest blessings cannot be measured by money or marble, but by memories and meat, time and place, sweat and smiles.

Unorthodox Gear for Mountain Zebras

Taking a lever-action rifle on an African safari is unconventional to begin with, but choosing Henry’s All Weather Picatinny Rail Side Gate rifle in the .45-70 Government chambering with flying tank ballistics seems downright nonsensical on paper, especially for a “mountain” hunt. However, my love for the round means finding workarounds for its shortcomings, and outfitter Stephen Bann of SB Hunting Safaris (sbhuntingsafaris.com) was up for the patience-testing challenge of stalking mountain zebras with such a setup.

I topped my rig with Leupold’s VX-3HD optic in 2.5-8×36. That magnification proved more than ample, while the smaller objective diameter allowed me to mount the optic low and tight for proper eye alignment, which can be tricky on lever guns.

The star of the optical show, though, is Leupold’s CDS-ZL system, for which the company builds a complimentary caliber-matched turret, in this case customized for my chosen Federal Premium Hammer Down 300-grain load. With a mountain zebra standing at 225 yards, all I needed to do is spin the turret to 2.25 and send it.

Not only does such a system take the guesswork out of holdovers, but also makes fast-falling rounds like the .45-70 a friendlier player on longer shots. Of course, there’s no replacement for getting close and enjoying the thrill of the hunt, but the right gear and proper preparation builds confidence for any eventuality. By safari’s end, my smooth-cycling lever gun proved itself on everything from Cape buffalo to springbok and ostrich, but in many ways, those wily mountain zebras posed the greatest ballistic challenge.