On a real hunt, the outcome is never assured.

Photo above: This was home for two weeks during the 2023 Alaska Peninsula brown bear season. Boddington saw a big bear three times, but came home empty-handed.

I just got back from a wet, windy brown bear hunt on the Alaskan Peninsula. I saw a good bear in the 10-foot class three times. There’s no sprinting in muskeg, and we were glassing him from a distance. Every time we got to the last place we’d seen him, he’d vanished, swallowed up in the big country. End result: No bear.

As my friend Conrad Evarts described me on my seventieth birthday, I’m “pathologically optimistic…and dangerously masochistic.” I don’t mind tough hunts, and I always go in expecting success. If success weren’t anticipated, I don’t know how I could put myself through this stuff. Great expectations aside, the reality of hunting is we can’t always make things happen.

I hate to get beat, and I hate it even more on a difficult and costly hunt like an expedition for an Alaskan brown bear. To some extent, it’s mind over matter: The country doesn’t mind, and we don’t matter.

On another level, it’s the very unpredictability of hunting that makes it so attractive. On any given outing, we don’t know what’s going to happen. For sure, we can’t control weather and game movement. So, we make the best plans, trying to hit the right places at the best times. We bring the right gear, get in the best shape possible, and spend plenty of time at the range so we can take advantage of an opportunity. Even so, sometimes it’s just not going to happen. It’s a bitter pill to swallow, but if you can’t choke it down, you’re in the wrong game.

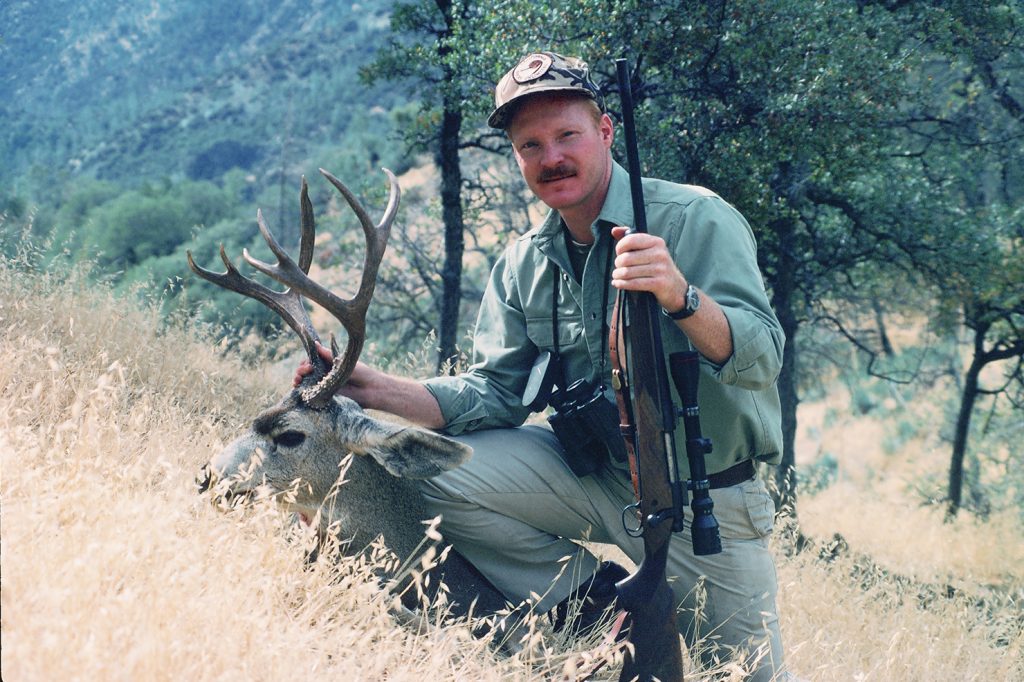

Random luck is a factor. You might hunt as hard as you can, but sometimes the right animal can’t be found or doesn’t present itself for a shot. Some hunters seem luckier than others, but this comes and goes. When I was a young hunter, I seemed charmed. Wherever I went, I filled my tag. My Dad called me “Lucky Pierre.”

Sooner or later, even the luckiest (and best) hunter gets a comeuppance. Mine was on my first safari, in Kenya. The animal I wanted most was a lion. I’d read Hemingway and Ruark. I figured if you paid your money and hunted hard, you’d get your lion. By the mid-1970s, chances weren’t nearly as good as I thought, but I didn’t know that. I passed a couple of young males on about the eighteenth day. The PH and I were both proud of ourselves that we passed. The twentieth and next-to-last evening, we heard what sounded like a good lion roaring in Tsavo Park. He didn’t come in, and that was that. The safari ended with no lion. I was all in on that hunt, with my budget stretched thin. It was a bitter pill to swallow, and a good lesson.

I’ve been pretty lucky over the last forty-five years. Still optimistic, I always expect to take the animal I’m after. It doesn’t always happen, in part because I’m not the same hunter I was back then. I’m pickier now, and the more selective we are, the worse our chances.

Everybody knows Arizona holds some of the biggest Rocky Mountain elk, and the odds for drawing are poor, especially for nonresidents. I’ve had three Arizona elk tags and I never got a monster wapiti. Once, if I must admit it, it was because I missed. Hunt enough, and that’s going to happen. When it does, the game isn’t obligated to offer a second chance.

Those Arizona elk hunts were golden opportunities, and I was hoping for greatness…but there were never any guarantees. When you swing for the fences, it must be accepted that you might strike out. Mind you, I don’t always look for the biggest and best. I’m usually happy with a nice, representative animal. In part, this is because I’m a gunwriter, always on a limited budget, and I want to get a good story. Reasonable expectations greatly increase the odds.

Sometimes I break from that, such as on those Arizona elk hunts, but when you pass a good animal looking for a huge one, you are taking a chance. I shot a couple of OK grizzlies when I was young, but later I decided I wanted a big grizzly. Dave Leonard, who hunts the Noatak drainage north of Kotzebue, Alaska, has big grizzlies in his area. The first time I went, it was too early; the bears were just coming out of their dens. The second time, it was too late. There was an early spring, with snowmelt coming fast, and we had to get out. Despite poor conditions, we passed OK bears on both hunts, but I didn’t see the bear I wanted. Fair enough. I tried one more time and hit it right. The third time was the charm, and I took a wonderful grizzly on a moose kill.

Persistence counts. So does planning, but even with the best planning, there are no promises. It’s just part of the deal. Some animals are more difficult than others, and so are some places. In the entire world of big-game hunting, North America offers some of the most difficult hunting, with some of the worst odds for success. Our North American Model of wildlife management dictates that wildlife is a public trust resource, jointly owned by all of us. This is a huge success story and I love it, but it means that our resources are shared among the hunting public. And it means the harvest is often limited by short seasons, which may not be at the ideal time.

Elsewhere in the world, wildlife is often privatized, or owned by the government. As visiting hunters, we are paying for the privilege and funding management, and there are often fewer hunters in the field. This makes hunting on other continents, on average, far more successful than in Canada and the United States.

Most of my hunts in Europe, Asia, South Pacific, and South America have been successful for the primary game sought. In North America, some of our greatest hunts offer less than 50 percent odds. These include most hunts in Alaska and Canada for elk, moose, the big bears, and sheep. I’ve been generally lucky on sheep and elk, not so much on moose. Newfoundland has Canada’s densest moose population. It took me four tries to get a nice Newfie moose, and in the last decade I’ve been 0 for 3 on western Canada moose.

Research and planning help, but there are still no guarantees. Deal with the possibility of failure, and be certain you’re prepared. It’s easy to say that you’re there for the experience and the memories. Win, lose, or draw, these you will have, but it’s tough when you head home empty-handed, having expended much effort and treasure with nothing tangible to show.

When possible, I like to hedge my bets with consolation prizes. This means combination hunts. Africa is wonderful for this, with multiple species almost always available. You may not take your primary animal, especially if it is one of the difficult prizes. I didn’t get a lion on that first safari. As consolation, I took most of the East African antelopes, plus the memories of hunting in soon-to-close Kenya. To be honest, it was some years before I appreciated these as much as I do today. I also didn’t get a bongo on my first try, nor a Derby eland on my first hunt for them, and I’ve been beaten by leopards more times than I’ve won.

The blow of failure is softened by success on other species. That said, I cannot argue against the tactic of concentrating on the game you want most, ignoring the rest. Just understand you are going for broke. Thirty years ago, I did that on my first giant eland hunt, passing opportunities for buffalo, kob, waterbuck, and more. I shot nothing at all on that safari, the only time that has happened in my African experience. Since then, I haven’t played an African hunt quite that way!

Armenia was my only unsuccessful Asian hunt. It’s a beautiful country, with friendly people, but I was on a spring hunt after a winter of record snows. The Armenian sheep were across the border in Iran behind snow-blocked passes, and the bears were still in their dens. There were plenty of Bezoar goats around, and they were on license. Hoping for a break, I declined. I don’t regret it because I already had a good Bezoar from Turkey. If I didn’t already have one, I’d have taken the consolation prize!

I talked to a Kansas neighbor just back from his first out-of-state hunt. He went to New Mexico for elk and pronghorn. He didn’t get an elk, which is hardly uncommon. But he was delighted with his excellent pronghorn, a fine consolation prize.

Combinations aren’t always possible. On my unsuccessful brown bear hunt, we had several excellent caribou bulls pass by our spike camp, but the season was closed. We took some good photos, watched ptarmigan and porcupines, and hoped for a break that didn’t come our way. All you can do is make the most of it. I’m older now, and I understand that’s the way it goes sometimes. I hope I can give it another try.